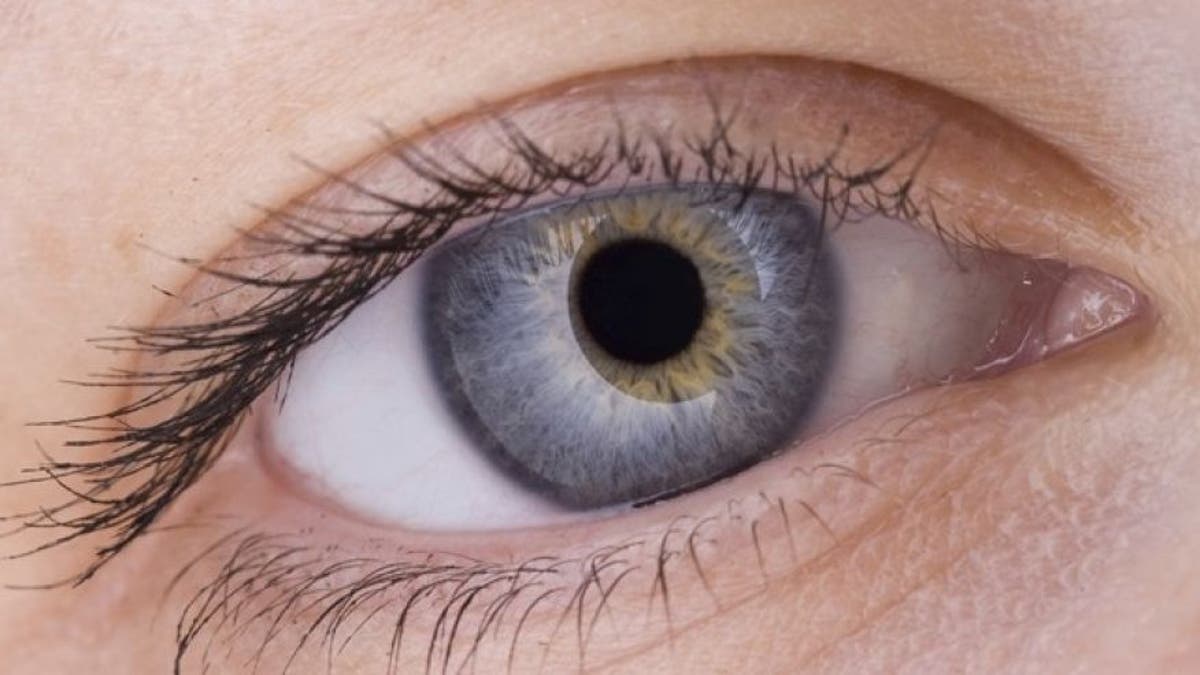

The case was detailed in the New England Journal of Medicine. (iStock)

Three elderly women who underwent an unapproved stem cell “treatment” for macular degeneration became legally blind from the procedure, physicians who later treated the patients reported on Wednesday. It is the latest evidence that for-profit stem cell clinics are “peddling the modern equivalent of snake oil” in a “gross violation of professional and possibly legal standards,” said Dr. George Daley, a leading stem cell biologist and dean of Harvard Medical School, in an editorial accompanying the study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The women, ages 72 to 88, were all treated in the summer of 2015 at Florida-based Bioheart Inc., which last August changed its name to US Stem Cell.

Each woman received a slurry of cells derived from liposuctioning her belly. US Stem Cell employees processed the tissue to isolate what the study authors call “the putative stem cells.” Those were mixed with platelet-dense plasma from the patient’s blood, treated with an enzyme, shaken, spun, and injected into both eyes.

The women all suffered detached retinas, vision loss, and hemorrhages in their eyes. While previously they just had trouble reading small print, afterwards they could barely see hand movements or, in some cases, light.

More From Stat News

Read more: FDA chief pushes back against criticism of stem cell treatment regulations

None of the women are named in the study. But at least two US Stem Cell patients, Elizabeth Noble and Patsy Bade, sued the company and some of its employees in 2015 after having stem cell procedures for macular degeneration that June. Both lawsuits were settled, with the women receiving payments.

The paper comes in the wake of efforts by the Food and Drug Administration to more tightly regulate stem cell clinics and close down those that put patients at risk. Those efforts have stalled, however. An FDA spokeswoman told STAT she has “nothing to share at this time” about the status of proposed regulations, and experts consider FDA action unlikely in the regulation-averse Trump administration.

In general, clinics have argued they are not subject to regulation of procedures using stem cells taken from a patient’s own body as long as those cells are “minimally processed.”

“There is little question that when the FDA is involved in regulatory oversight it works in favor of patient safety,” said Stanford University’s Dr. Jeffrey Goldberg, senior author of the NEJM paper. “That would have protected patients in cases like these.”

Clinical trial?

The company appeared to have plans to do more such procedures. A clinical trial run by Bioheart, first listed in a government database in 2013, was withdrawn in September 2015 before it enrolled anyone.

At least one woman said she thought she was in a clinical trial that she found in that database. In fact, however, the consent form she signed was simply to undergo the stem cell procedure, said Dr. Thomas Albini, of the University of Miami, who treated two of the women days after their procedures, when they were in pain and becoming blind. (The third was treated at an Oklahoma eye institute.)

Read more: Stem cell clinics hawking unproven therapies sprout up across US

Each woman paid $5,000 for the procedure. Virtually no reputable clinical trial charges patients for a procedure that is supposedly being studied. The clinical trial listing “lured these women into thinking this was a legitimate procedure and could help them,” Albini said.

In response to requests for comment, US Stem Cell’s public relations firm said in a statement that, since 2001, its clinics “have successfully conducted more than 7,000 stem cell procedures with less than 0.01 percent adverse reactions reported.” The spokeswoman said the company would not comment on whether the women believed they were enrolling in a clinical trial or why it withdrew the trial before enrolling any patients.

It is not clear what went wrong in the three cases. One possibility is that the slurry contained cells that contracted, literally pulling the patients’ retinas off the back of the eye. Alternatively, enzymes used to prepare the fat cells might not have been washed off before the slurry was injected, and may have attacked the patients’ eyes. The women’s blindness “was obviously due to the procedure,” Albini said, calling it “off-the-charts dangerous.” Not only is there no reputable research showing stem cells derived from fat and injected into the eye are safe and effective, but it was done on both eyes at once — a no-no even for established ophthalmological procedures.

Nor is it clear what the company thought the fat-derived stem cells would do in eyes. No stem cell expert contacted by STAT knew of any studies by the company testing the procedure in lab animals. “This case is a perfect example of why doing preclinical studies [on lab animals] is so important,” said Paul Knoepfler of the University of California, Davis, a stem cell biologist who follows the industry and was not involved in the new study. “Doing the procedure in rats might have shown whether there are safety problems.”

US Stem Cell no longer performs eye procedures. In a regulatory filing, it reported that its techniques can treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hip and knee conditions, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, autism, colitis, and lupus. There is no rigorous evidence that stem cells spun out of patients’ fat can safely and effectively treat any of these, and none are FDA-approved.

What was then Bioheart became a publicly traded company in February 2008, raising $5.8 million, one-tenth what it had forecast. The stock is currently trading at a little below 3 cents per share and the company is known for “really preaching the gospel for stem cell therapy and the need for less FDA oversight,” said Knoepfler.

At a recent FDA hearing on stem cell clinics, US Stem Cell’s chief scientific officer, Kristin Comella, said, “The government should not regulate our bodies. … I will always stand up for patient rights.”