Multiple sclerosis (MS), a central nervous system disease that often leads to paralysis and vision problems, affects approximately 2.3 million people worldwide and has no cure. Though no one knows what triggers MS, researchers have long suspected that a combination of genetic and environmental factors influence a person’s risk of developing the disease.

Now, researchers from Weill Cornell Medical College have pinpointed a specific toxin they believe may be responsible for the onset of MS, offering hope for future therapies or vaccines to prevent the condition.

The potential trigger: epsilon toxin, a byproduct of the bacterium Clostridium perfringens – better known as one the most common causes of foodborne illness in the United States.

“[Earlier research] in the lab has shown that MS patients are 10 times more immune-reactive to the epsilon toxin than healthy patients,” Dr. Jennifer Linden of Weill Cornell Medical College told FoxNews.com. This finding ultimately prompted Linden and her colleagues to examine the link between the toxin and MS more closely.

According to earlier animal studies, epsilon toxin acts similarly to MS, in that they both have the ability to permeate the blood-brain barrier – a filtration-like system that typically prevents toxins from travelling from a person’s blood into their brain.

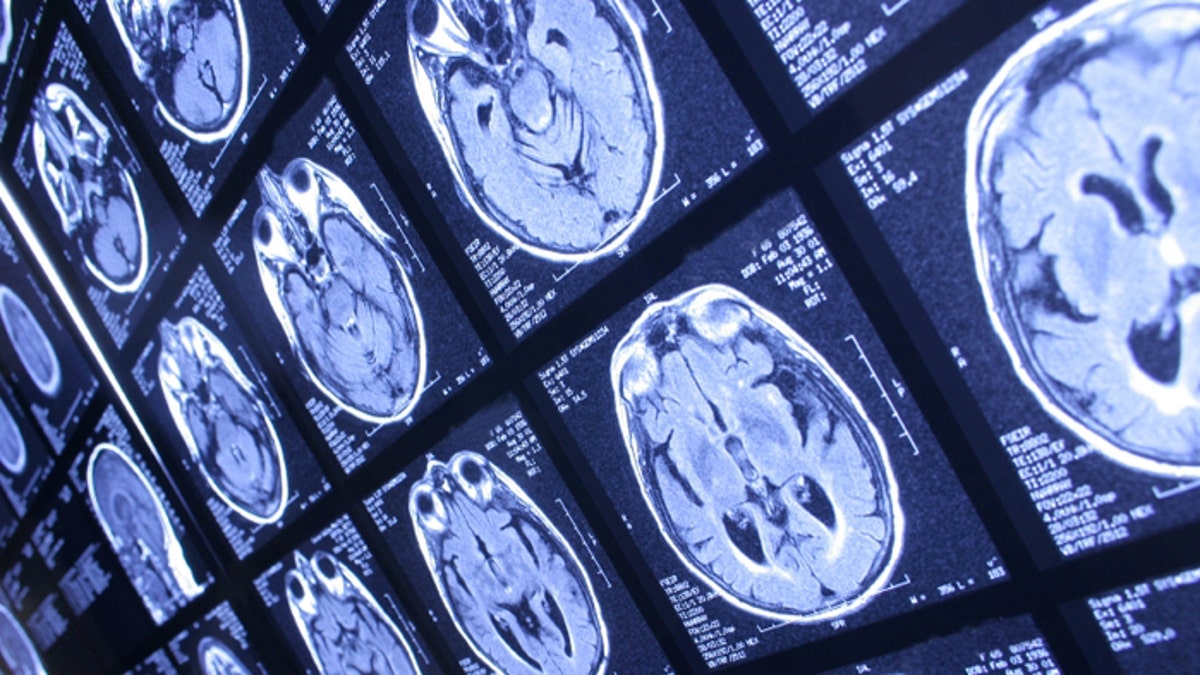

Now, new research presented by Linden and her colleagues at the 2014 American Society for Microbiology (ASM) Biodefense and Emerging Diseases Research Meeting indicates that epsilon toxin also kills cells that produce myelin – the protective sheath that surrounds neurons and allows them to transmit signals in the brain. Notably, this is the same reaction that occurs when people with MS develop lesions in their brains.

The researchers also discovered that epsilon toxin seemed to kill meningeal cells, which form the layer of membranes between the skull and the brain.

“In MS there is meningeal inflammation and it was interesting that the toxin also killed these cells,” Linden said. “What we’re finding out is this toxin seems to have an affinity for a lot of the cells affected in MS, aside from just the blood-brain barrier and myelin producing cells – specifically blood vessels in the retina and meningeal cells.”

Though further research is needed, the researchers said that if epsilon toxin is confirmed as a trigger for MS, it could lead to treatments and prevention tactics for the disease.

“We’d be able to develop therapies and treatments to prevent MS… [and] come up with a vaccine against epsilon toxin to prevent that damage from happening,” Linden said. “[We could] also come up with antibodies to neutralize the toxin and possibly come up with ways to keep people from becoming colonized or infected by epsilon toxin-producing bacteria.”

Though Clostridium perfringens is a common bacterium, the strain that produces epsilon toxin is relatively rare. Linden and her colleagues tested 37 produce samples for the presence of both Clostridium perfringens and epsilon toxin and discovered that while 13.5 percent tested positive for the bacteria, only 2.7 percent tested positive for epsilon toxin.

Furthermore, though Clostridium perfringens is a common cause of foodborne illness, the researchers warned that epsilon toxin isn’t necessarily transmitted through foods, and they do not yet know exactly how people are contracting the toxin.

“Being exposed to it through food is just an idea,” Linden said. “It’s always a good idea to practice good personal hygiene and to cook and clean your food properly, but it is too early to tell what the dangers are.”