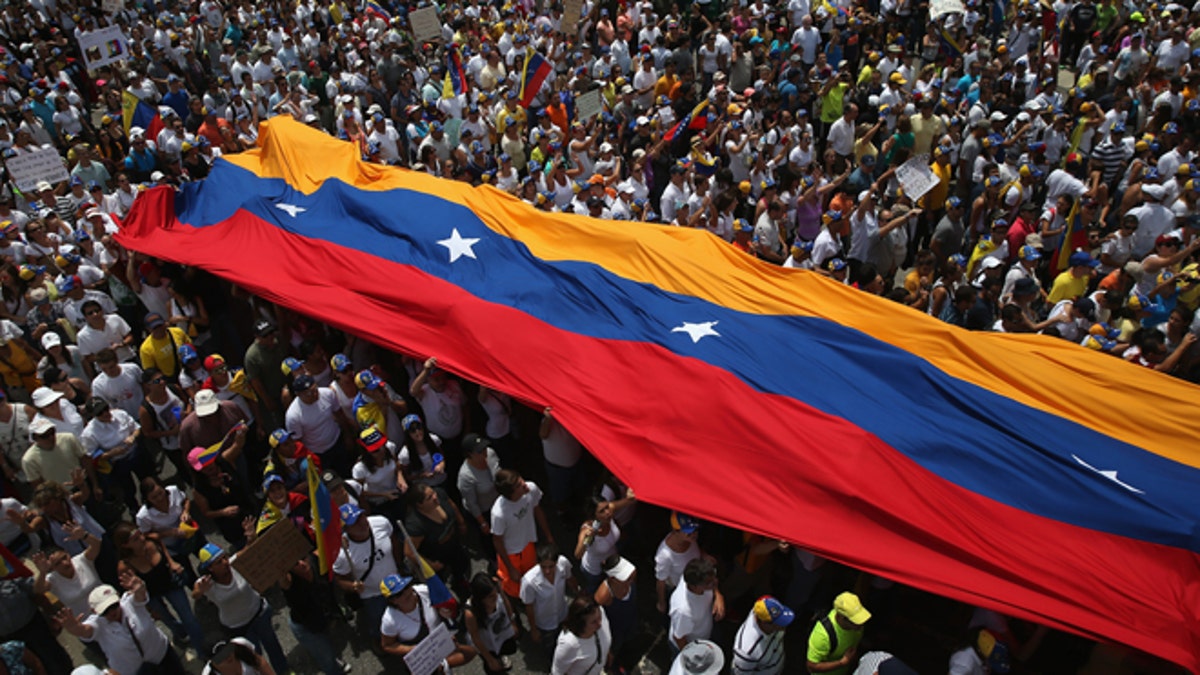

CARACAS, VENEZUELA - MARCH 02: Thousands of protesters march in one of the largest anti-government demonstrations yet on March 2, 2014 in Caracas, Venezuela. Venezuela has one of the highest inflation rates in the world, and opposition supporters have protested for almost three weeks, virtually paralyzing business in much of the country. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images) (2014 Getty Images)

A lawsuit filed Wednesday by Venezuelan National Assembly President Diosdado Cabello against three newspapers that republished a Spanish newspaper article – alleging that Cabello and other members of the Venezuelan government were involved in the illicit drug trade – is the latest in a series of crackdowns on free speech in a country reeling from economic, political and civil unrest.

While the lawsuit may not become the most extreme example of the hardline moves implemented by the government of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, analysts say his administration continues to try and silence critics and shutdown unrest ahead of the crucial parliamentary elections later this year – one that experts say could decide the fate of the struggling country.

"Given the lack of institutions in Venezuela, the political polarization and the high levels of mistrust in the government, it looks likes things are not going to end well for Venezuela," Chris Sabatini, a professor at Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) told Fox News Latino.

For years, Venezuela's economy was buoyed by profits from its booming oil industry, allowing the country under late socialist leader Hugo Chávez to invest heavily in numerous social projects, both at home and abroad, and parlay the OPEC nation's position as one of the world's top oil exporters into that of a regional power.

But as social spending increased, Venezuela's windfall profits soon began to run dry thanks in part to falling oil prices, rampant inflation, corruption and the nationalization of key business sectors – leaving Chávez's successor, Maduro, struggling to deal with a floundering economy, rampant crime rates, isolation on the world stage and widespread discontent at home.

The elections could possibly restore some trust in at least some of the country's institutions and if they're transparent allow the opposition to make some gains that could eventually turn the country around.

When it last reported its inflation rate in late December, Venezuela had the world's highest at 69 percent, and economists say that the rate could nearly double this year as the country struggles to respond to falling oil prices. With the price of Venezuelan oil dropping around 50 percent in the last year from around $88 a barrel to $45 a barrel as of April, Venezuela has been forced to drastically reduce imports – creating shortages of basic goods – and weakening the bolivar 74 percent over the past year to around 257 bolivars per dollar, compared with the official rate of 6.3 for priority imports, according to Bloomberg.

Many observers say that these problems are due in large part to Maduro government's reactionary politics and lack of any meaningful economic plan.

"The government doesn't have any form of economic policy," Sonia Schott, the former Washington D.C. correspondent for Venezuelan news network Globovisión told FNL. "We are in the middle of a major crisis."

The crisis appeared to reach a boiling point last February following the arrest of Leopoldo Lopez, a former Caracas-area mayor and key opposition leader. Widespread unrest following his arrest left 43 people dead and neighborhoods disrupted by flaming barricades.

Over a year later, the unrest has died down but little appears to have changed for the better and most in the capital city of Caracas would argue that the country's situation has gotten worse. A few dozen protesters remain imprisoned, the government continues to arrest anti-Maduro supporters and people in Caracas stand in long line for hours for everything from toilet paper to flour.

"Outside of Venezuela, the opposition looks very strong because you hear their voice a lot," Caracas-based political consultant Dimitris Pantoulas told the Associated Press earlier this year. "But here, you see that people have lost their hope that there might be change on the horizon."

Analysts say that if Venezuela has any hope of crawling out of the dilemma currently embroiling the country, the best starting point will be the upcoming parliamentary election that will occur sometime by the end of the year, although the country's National Electoral Council has not set an exact date despite pressure at home and abroad. Elections for the National Assembly are scheduled every five years and must be held by the year's end.

Political polls indicate that Venezuela's opposition coalition, which holds a third of the legislature, has a very good shot at dominating an election for the first time since Chávez launched his 21st Century socialist revolution 16 years ago. If the coalition manages to win control of parliament, it is expected to use its legislative power to mount a recall referendum against Maduro.

One issue, however, facing Venezuela’s opposition is that the anti-Maduro coalition is made up of dozens of sometimes discordant political parties who will have to coalesce following this Sunday’s primary election to present a united front against Maduro’s socialist party come the general election later this year.

"The last exit before Venezuela faces a serious collapse is going to be these elections," Sabatini said. "The elections could possibly restore some trust in at least some of the country's institutions and, if they're transparent, allow the opposition to make some gains that could eventually turn the country around."

Rampant corruption is one of the main worries cited by many observers in the run-up to Venezuela's parliamentary elections.

Watchdog group Transparency International ranked Venezuela as one of the most corrupt countries on the planet – putting them as the 161st least corrupt country out of 175 nations. It cited the country's political institutions, judiciary and police as being the most affected by corruption.

And while Maduro has promised to hold clean and open elections by the end of the year, many are taking his words with skepticism given the continuing crackdown on opposition voices and free speech.

"How can a country move forward when all the people who speak out are silenced by the government," Schott said. "The big question now is, “are we going to have transparent elections?"