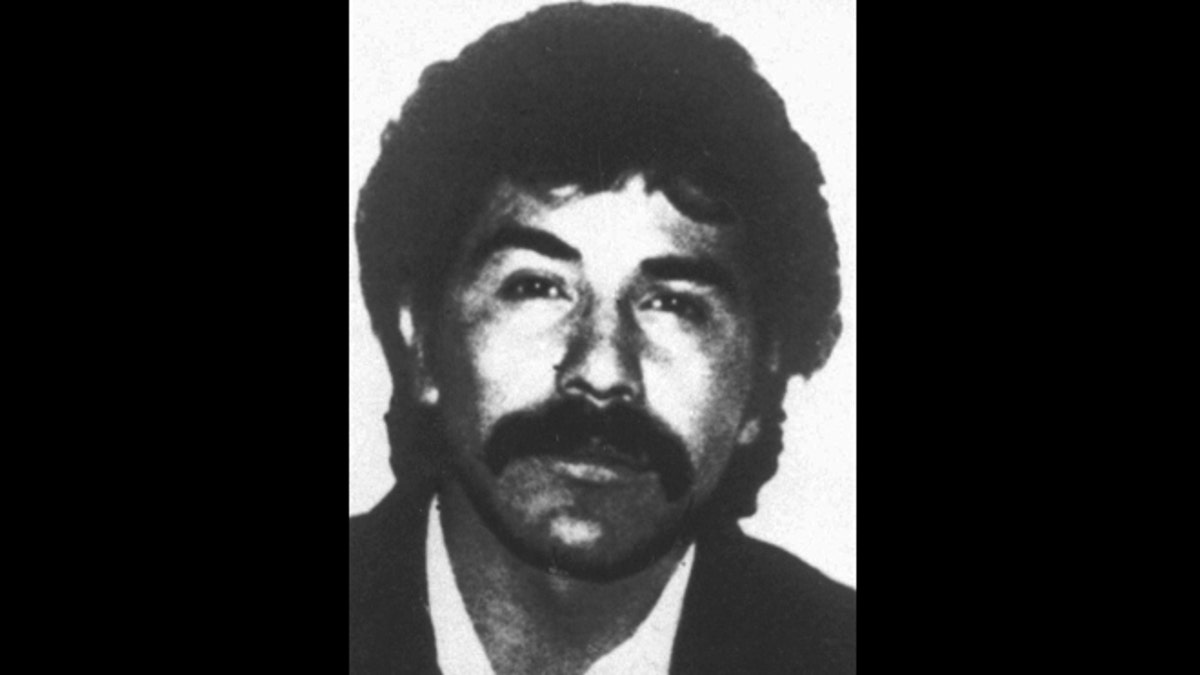

Undated file photo distributed by the Mexican government shows Rafael Caro Quintero, considered the grandfather of Mexican drug trafficking. (ap)

Mexico City, Mexico – Mexico's Supreme Court has voted to overturn an appeals court decision to release drug lord Rafael Caro Quintero and is ordering the court to reconsider the case.

The 4-1 decision by a panel of five Supreme Court justices to overturn Caro Quintero's release came after the United States offered a reward of up to $5 million for information leading to his arrest and conviction.

Caro Quintero was 28 years into a 40-year sentence for helping orchestrate the 1985 killing of U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agent Enrique "Kiki" Camarena when he was surprisingly released in August. A Mexican court threw out his sentence, arguing he was improperly tried in a federal court for a crime that should have been treated as a state offense.

Now Caro Quintero has been indicted by the U.S. attorney's office for the Central District of California on a host of U.S. federal felony charges and is considered a fugitive from justice.

The 61-year-old Caro Quintero is considered the grandfather of Mexican drug trafficking. He established a powerful cartel based in the northwestern Mexican state of Sinaloa that later split into some of Mexico's largest cartels, including the Sinaloa and Juárez cartels.

Mexico's relations with Washington were damaged when Caro Quintero ordered Camarena kidnapped, tortured and killed, purportedly because he was angry about a raid on a 220-acre marijuana plantation in central Mexico named "Rancho Bufalo" — Buffalo Ranch — that was seized by Mexican authorities at Camarena's insistence.

The raid netted up to five tons of marijuana and cost Caro Quintero and his colleagues an estimated $8 billion in lost sales.

Camarena was kidnapped on Feb. 7, 1985, in Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco state and a major drug trafficking center. His body and that of his Mexican pilot, both showing signs of torture, were found a month later, buried in shallow graves.

American officials accused their Mexican counterparts of letting Camarena's killers get away. Caro Quintero was eventually hunted down in Costa Rica.

Mexican courts and prosecutors have long tolerated illicit evidence such as forced confessions and have frequently based cases on questionable testimony or hearsay. Such practices have been banned by recent judicial reforms, but past cases — including those against high-level drug traffickers — are often rife with such legal violations.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino