Turkey imposes tariffs on US goods as tensions rise

Ankara doubles down on tariffs on U.S. imports amid a currency crisis and tensions over the country's refusal to release American Pastor Andrew Brunson; Rich Edson reports from the State Department.

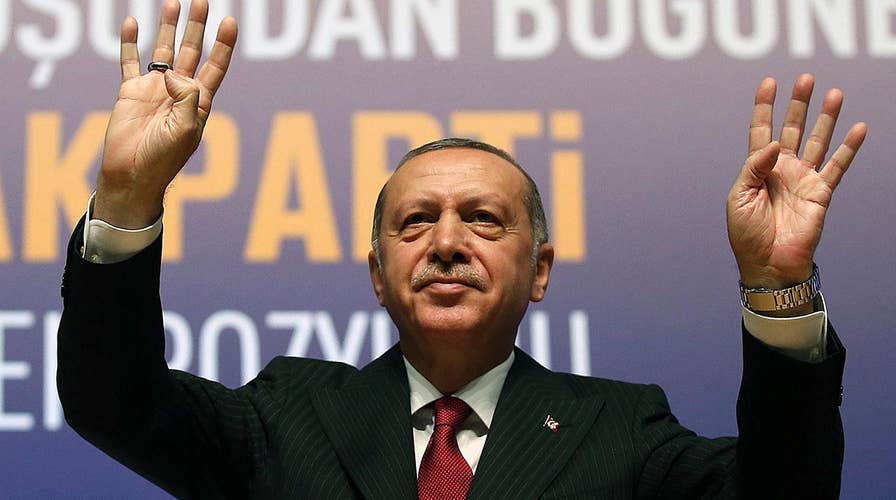

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's effort to blame Trump administration sanctions for that country's recent economic woes is off-base and ignores years of missteps and miscalculations that set the stage for the current crisis, according to experts.

“Turkey’s economic downturn has long been in the making. The latest tailspin is a result of structural problems that economists have warned about for years,” said Aykan Erdemir, Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

Erdemir said the problems can be traced back as far as 2009, when Erdogan issued a decree easing Turkish companies' access to foreign-exchange loans that led to $340 billion in foreign liability. And most of that money, Erdemir said, went into conspicuous consumption and lavish real estate projects typical of Erdogan’s "crony-capitalist model," which thrived for a decade but "is now going through a hard landing.”

Relations between the NATO allies is said to be at an all-time low. (File)

Dennis Santiago, a global risk and financial analyst, agreed that “the seeds of Turkey’s economic woes were planted long before Turkey, along with all other nations, felt the pressure of President Trump’s agenda to rebalance tariffs.”

“Turkey went on a foreign investment borrowing spree to buoy its ‘emerging market’ economy. It’s foreign debt exposure is high compared to other emerging economies,” Santiago explained. “The aggressive policy resulted in rapid domestic growth for the Turks in recent years. However, like all such strategies, these are artificial ‘bubble growth’ strategies that inevitably hit a plateau.”

FRUSTRATED SUPPORTERS OF ACCUSED US PASTOR IN TURKEY KEEP UP THE PRESSURE

A country’s central bank will typically tighten up rates and adjust inflation up to take the sting out of the end of the bubble, Santiago noted. But Erdogan pressed to sustain rapid growth longer than its natural balance point, and prevented the Turkish central bank from doing its moderating function.

“This left the Turkish economy unusually vulnerable to ‘external shock’ events compared to other emerging market countries,” he said. “So it’s natural that Turkey’s economy would react in a more volatile manner to a global tariff realignment initiative like the one presently being undertaken by the United States.”

Indeed, the recent erraticism of the Turkish currency, the Lira, knocked hundreds of points off global markets in just a few days and generated sell-offs across emerging markets. A year ago, one U.S dollar bought around 3.5 lira but as of Monday morning, it bought just above 6.

The detainment of American Pastor Andrew Brunson has cast a spotlight on Turkey's long coming economic woes. (AP)

INSIDE RAQQA: FROM ISIS 'CALIPHATE' TO CRUMPLED CITY OF LANDMINES, AND LOSS

Over the past month alone, the Turkish Lira depreciated around 40 percent of its value against the U.S. dollar – making it difficult for Turkish businesses and consumers to repay debts, slowing economic growth by paving the way for less lira to spent on other things, and then halting economy growth if debtors are unable to repay their loans and subsequently default.

The original causes of Turkey’s deepening monetary woes are internal, analysts widely contend, even if the recent blows triggered by U.S sanctions and tariffs amid the Brunson standoff are causing a quicker collapse.

“Consumer prices started accelerating in early 2017 fueled by a large depreciation of the Turkish lira,” Murray Gunn, Head of Global Research at independent market analysis firm, Elliott Wave International. “This added momentum to developing social unrest.”

Some experts are now going as far as to anticipate a 2019 recession for the Middle East country of 81 million – with Turkey’s debt edging dangerously close into what is considered non-investment, or “junk” territory.

Nonetheless, experts remain divided on whether even that would severely rattle global markets, or if it will mostly just hurt the people of Turkey, given that the country only accounts for an estimated 1.4 percent of the global GDP.

“This is the million-dollar question. The U.S economy is going great, and will likely roll over this like a tiny speed bump. But is this going to impact the Eurozone? We still have allies there we want to do well,” said Lester Munson, former Staff Director of the Foreign Relations Committee and now a Visiting Fellow at George Mason’s National Security Institute. “It also could allow bad guys like Russia and China to move in and have greater influence.”

Yet Turkey is doing little in the way of squashing a possible crash, economists say.

Erdogan has long called himself “the enemy of interest rates” and rallied against allowing the central bank to practice monetary tightening, heralding popular support among his voter base by focusing on accelerated prosperity rather than curbing inflation, which has ascended to over 15 percent.

Following Turkey’s snap elections in June, Erdogan entrusted both the Finance Ministry and the treasury to his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, further solidifying his control over the country monetarily. Amid the latest rollercoaster, banking authorities have pursued short-term solutions to save the plunging lira, such as putting a pause on outside currency exchanges to stop traders chancing against the currency and urging people to swap their American dollars and gold.

Erdogan has further deflected all responsibility for his nation’s currency crisis – blaming the U.S. and drumming up popular support by declaring that his country is not “going to take it sitting down.”

“An attack on our economy is no different from a direct strike against our flag and call to prayer. The purpose is no different. It aims to bring Turkey and the Turkish people to their knees,” Erdogan said in a public message early Monday. “We are a kind of people who prefer to be beheaded instead of being chained around the neck."

But many policy professionals say it is only a matter of time before the Band-Aid is eventually peeled or harshly ripped away.

“At this point, Erdogan finds it convenient to point the finger to Washington, and blame the economic crisis on economic warfare by what he refers to as ‘the interest rate lobby.’ In the eyes of his loyalists, this absolve the Turkish strongman from any responsibility,” Erdemir added. “But as long as Erdogan is in denial mode, Turkey will not be able to initiate much-needed structural reform required to put the economy back on track.”