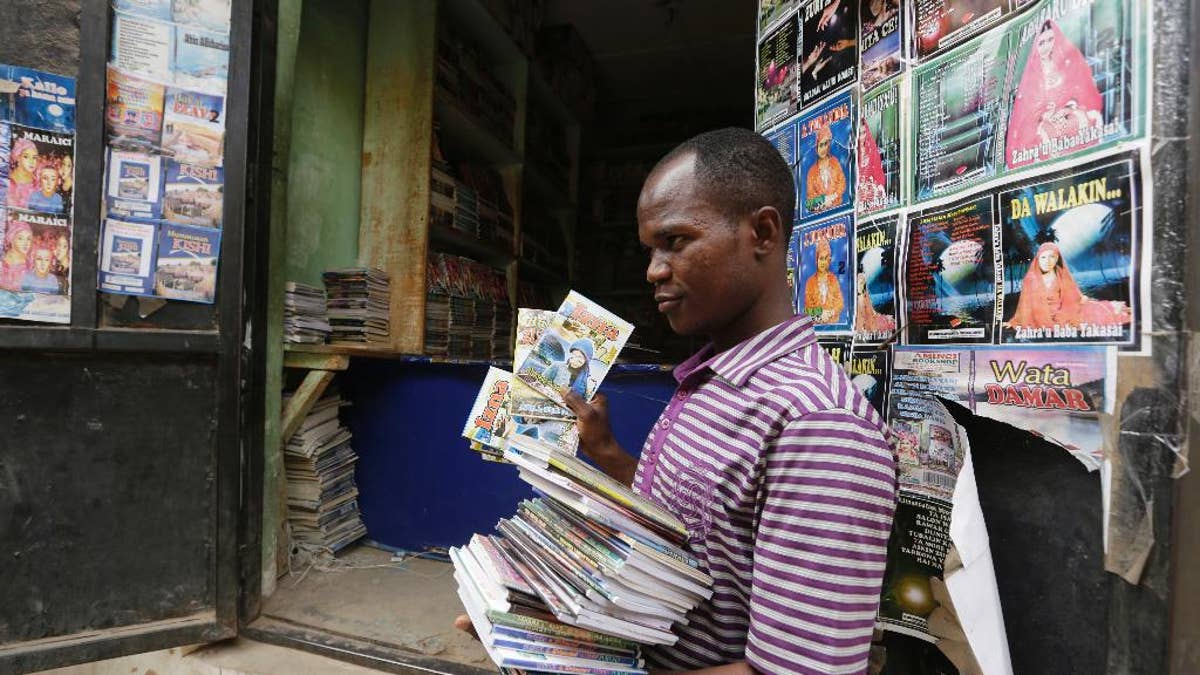

In this photo taken Monday April, 4. 2016, a Book hawker, Adamu Saidu, displays books he purchased at Kurmi Market to be sold in villages inaccessible by car in Kano, Nigeria. In the local market stalls are signs of a feminist revolution with piles of poorly printed books by women, as part of a flourishing literary movement centered in the ancient city of Kano, that advocate against conservative Muslim traditions such as child marriage and quick divorces. dozens of young women are rebelling through romance novels, many hand-written in the Hausa language, and the romances now run into thousands of titles. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba) (The Associated Press)

KANO, Nigeria – Nestled among vegetables, plastic kettles and hand-dyed fabric in market stalls are the signs of a feminist revolution: Piles of poorly printed books by women that advocate forcefully against conservative Muslim traditions such as child marriage and quick divorce.

These books are part of a flourishing literary movement centered in the ancient city of Kano, in northern Nigeria, where dozens of young women are rebelling through romance novels. Hand-written in the Hausa language, the romances now run into thousands of titles. Many rail against a strict interpretation of Islam propagated in Nigeria by the extremist group Boko Haram, which on Sunday posted video showing dozens of the 218 girls militants abducted from a remote school in April 2014.

"We write to educate people, to be popular, to touch others' lives, to touch on things that are happening in our society," says author Hadiza Nuhu Gudaji, 38, a veteran of the movement who has gained a recognition unusual for women in her society. For example, Gudaji recounts how, on a radio talk show, she was able to persuade the father of a 15-year-old not to force his daughter into marriage.

The novellas are derogatorily called "littattafan soyayya, meaning "love literature," Kano market literature or, more kindly, modern Hausa literature. Daily readings on about 20 radio stations make them accessible to the illiterate.

"It's a quiet revolution," says Ado Ahmed Gidan Dabino, a male novelist, essayist, actor and head of the Kano branch of the Nigerian Writers' Association. "Nothing hard-hitting, but small, small, and gradually challenging."

They have become so popular that young girls call in to say they're learning to read because they want to follow more stories. That is no minor feat in a region where only one in five girls has had any formal education. Even the name Boko Haram means "Western education is sinful," and the group denounces the Western influences entwined with the romance genre — an argument Gudaji firmly rejects.

"What they are preaching and doing is not in the Quran," she says, waving a hand with a flower painted into the palm in violet-colored henna.

Although the romance industry caters largely to women, it's often men who profit. The best-known reader on the radio is a man, journalist Ahmad Isa Koko, who raises his voice an octave to imitate a woman's.

The Maharazu Bookshop has piles of paperback novels reaching to the ceiling, some gathering dust on the floor. Owner Suleiman Maharazu is going through a list from a middle-aged woman reader. The titles translate as "The Importance of Love," ''Big Tragedy," ''Your Face is Your Passion," ''The Beauty of a Woman is in Cooking," and "The Woman Who Lost Control."

"I don't read them, I just sell them," says Maharazu.

Only a couple of the Hausa novels have been translated into English. "Sin is a Puppy that Follows You Home" was translated by Indian publishers and subsequently made into a Bollywood movie. The book is available on amazon.com, which describes it as "an Islamic soap opera complete with polygamous households, virtuous women, scheming harlots, and black magic." Author Balaraba Ramat Yakubu was herself a child bride twice, after her first husband returned her to her family, and she only learned to read and write as an adult.

Critics say the novellas give girls unrealistic expectations, inspire rebellion and are un-Islamic. The most famous disgraced book is "Matsayin Lover," about lesbian love at a girls' boarding school, dating back to 1998. Abdulla Uba Adamu says his own friends and fellow writers forced him to remove the book from the market, though he insists it reflects reality.

Sometimes the reaction is violent. Last year, one young writer was badly beaten. Young men gang-raped another in her home after she published a book about women's rights in politics, according to Gidan Dabino. Some books are also banned or censored for steamy content that goes beyond a marital kiss.

Gudaji has an iPad and smartphone, but says she writes best by hand, lying on her stomach on her bed. The romances are cheaply printed with covers of photo-shopped stars from Nollywood, Nigeria's burgeoning film industry, or Bollywood, the Indian variety some writers are accused of plagiarizing. Many writers end up losing money.

Gudaji's first novel challenged a tradition where poor rural parents will send a child to family members in the city, hoping the child will be educated. Often they are turned into domestic slaves instead, ill-treated and raped by men in the home.

Her second novel addresses the scourge of divorce and how to deal with problematic husbands. In northern Nigeria, a man can divorce a woman simply by pronouncing three times, "I divorce you." When that happens, the former wife leaves alone and may not know what has happened to her children.

Even for Gudaji, tradition still holds. Happily married, she still has to seek the permission of her husband to allow two male journalists into her home. And she explains the role of a dutiful daughter when parents want to arrange an unwelcome marriage.

"A girl may love a boy but if they don't suit, you have to stop her, and a girl has to obey her parents — 100 percent," she says, looking at her oldest daughter, Khadija, nearly 21, and brooking no argument. "She must obey your rules and regulations."