Although the Great Wall has become China’s pre-eminent national symbol of pride and strength, the construction of its soaring watchtowers and crenelated parapets actually reflected a moment of dynastic weakness.

And it was, of course, a colossal failure. The present structure (popularly thought to track a wall erected by China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang) was mostly built during the later Ming dynasty in the 16th century to keep out fierce nomad tribes to the north.

Early Ming emperors had found other ways to pacify these groups: royal marriages, barter trade and other inducements. But as the dynasty crumbled, hard-line factions at court—the ideologues of their day—pushed for an impregnable barrier. It was necessary, they argued, to protect Chinese civilization against the “barbarian” hordes.

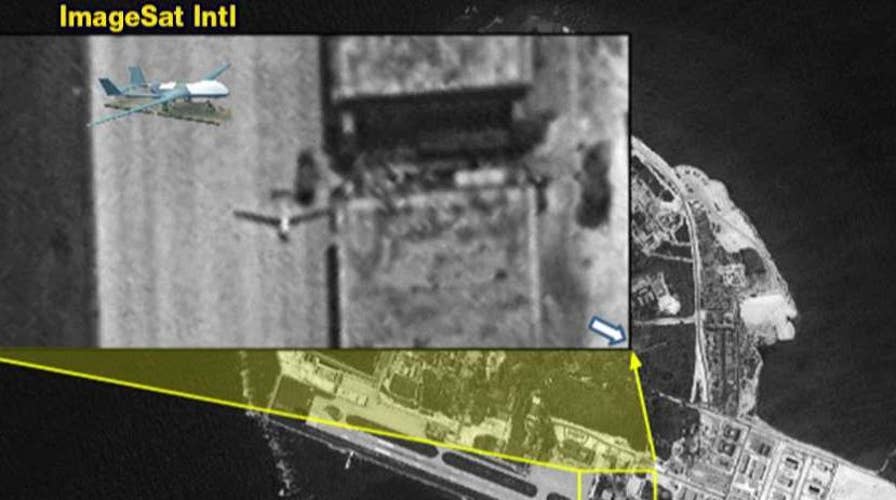

Echoes of this history reverberate today in the South China Sea, where China is building massive fortifications—artificial islands dredged from the seabed—to help defend a “nine-dash line” claim that encircles almost the entire waterway and reaches almost 1,000 miles from China’s coastline.

U.S. Adm. Harry Harris rails against the man-made islands as a “Great Wall of Sand.” Defense Secretary Ash Carter warns that China risks building a “Great Wall of self-isolation” through actions that have alarmed its neighbors.

In a matter of days, a United Nations-backed court in The Hague is expected to rule on a challenge to China’s claim brought by the Philippines. The decision will address an issue that has preoccupied Chinese dynasties since antiquity: Where does China end?

This has infuriated Chinese leaders; the presumptuousness of foreign jurists sitting in judgment upon what China regards as a matter of Chinese sovereignty is intolerable. Beijing has boycotted the proceedings.

Yet there’s an even more fundamental issue at play, one that dominated the debate in the old Ming court and that has rumbled on ever since: How should China conduct its relations with the world?

Now, as then, the question is inextricably wrapped up with China’s perceptions of itself. The way China responds to the ruling in The Hague will tell us a lot about the mind-set of a country that has alternated between bouts of isolation and pragmatic engagement.