Nuclear, solar power are hot topics at climate change summit

The United Nations' goal is to keep man-made warming below two degrees Celsius #COP21

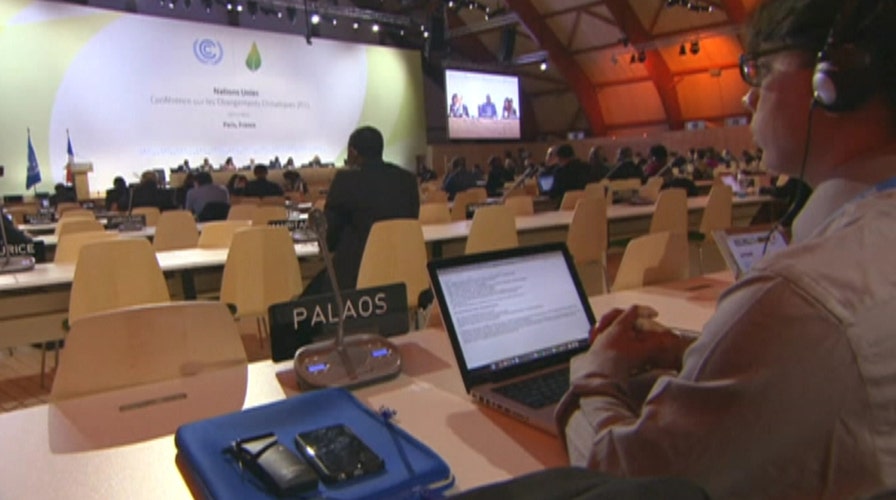

LE BOURGET, France – The once black-and-white world of climate negotiations for poorer countries has evolved into many shades of gray at talks this week in Paris.

For years, many in the developing world said richer countries created the global warming problem with their industrial emissions so it is up to them to clean it up — a sticking point in past climate negotiations.

But there's no way that global warming can be kept below the international goal of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial times without dramatic limits in future carbon dioxide emissions from the developing nations, climate experts and even officials from developing nations say. The Earth has already warmed up about 1 degree Celsius since then.

"Everybody has to participate in cleaning up the mess," said Richard Somerville, a Scripps Institution of Oceanography climate scientist. "If you are going to take it seriously, everybody has to play a part."

Tuvalu Prime Minister Enele Sosene Sopoaga said even though developing nations like his — which is being threatened with being wiped out by a rise in sea levels — didn't cause the global warming problem, they still have to limit future fossil fuel use because the problem has gotten so serious. But poorer nations need financial aid to help pay for renewable energy over often-cheaper fossil fuels.

"Yes they are ready, because they recognize it is a global issue," Sopoaga said Thursday. "Let's do it together."

China's climate change special envoy, Xie Zhenhua, said even though it will be difficult, China is committed to changing its energy system, peaking its emissions by 2030, if not earlier. China is by far the world's No. 1 carbon emissions polluter.

"This is not something imposed on us," Xie said Thursday at the Chinese pavilion at the Paris climate talks. "This something we Chinese want to do ourselves. And we will do it well."

At a Thursday news conference, some least-developed nations continued to make the case for an agreement that reflects that poor countries can't do as much as rich ones.

Pa Ousman Jarju, minister of environment and climate change of Gambia, called the issue "the elephant in the room."

"We are different. We have different capabilities," Jarju said. "We need to ensure that we have an agreement that would reflect those realities."

Nozipho Mxakato-Diseko of South Africa, who heads the bloc of developing countries in the climate talks, said the group was united and insisted that that's a good thing for everyone.

"If you have a fragmented group it makes the management of the negotiations that much harder," she said.

Janos Pasztor, the United Nations assistant secretary general for climate change, said if there is "one set of rules of the road" for nations regardless of rich or poor in the agreement, it will also have flexibility "so that the developing countries will also be able to deliver."

"Developing nations understand that they also have an increasing responsibility while recognizing clearly that the developed countries have to still take the lead," Pasztor said in an interview with The Associated Press. "You see that in their national plans."

The numbers are stark.

"Approximately two-thirds of avoided emissions would have to come from developing worlds," said Andrew Jones, co-director of the Climate Interactive, a group of scientists that use computer simulations to model how much warming will happen under different pollution cuts offered up in the international negotiations.

The reason for that is, under a scenario where emissions continue at the current pace, most of the pollution growth comes from the anticipated increase in fossil fuel use by developing nations, said Ellie Johnston of the Climate Interactive.

Former NASA chief climate scientist James Hansen, often considered the godfather of global warming research, said Thursday there is a sense of unfairness about climate change. He said the problem was caused by developed north nations, but it is felt by "nations at low latitude that did almost nothing to cause the problem."