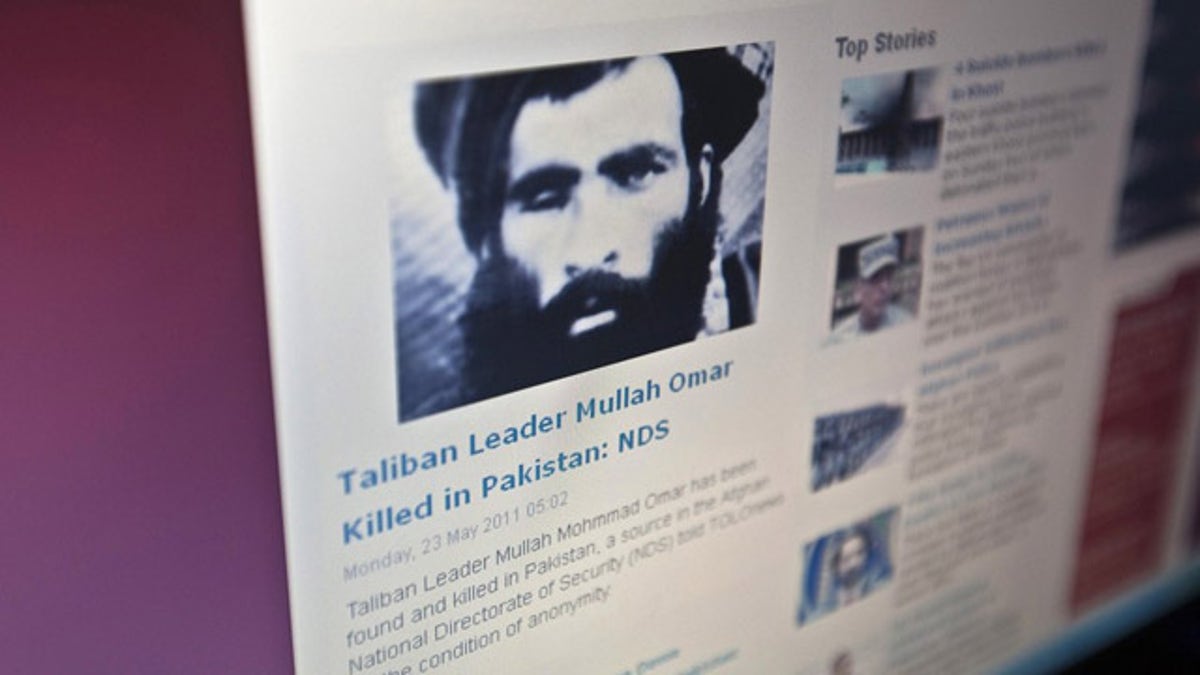

Reports of the death of Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar are nothing new, but it is rare for the Afghan government to give them credence. (Reuters)

The Taliban may be willing to sit with its enemies across a conference table, but that doesn’t mean they’re planning to lay down their arms any time soon.

“I rule out any possibility of cease-fire,” Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid told Fox News, in advance of a meeting in Paris. “We will not stop fighting.”

The comments came days before a non-government conference organized by the Foundation for Strategic Research in France, tentatively scheduled for Dec. 19-21, to discuss Afghanistan’s future. The Taliban says it’s preparing to send delegates to Paris for the event, as are Pakistan, Afghanistan, the Afghan High Peace Council, the National Front and Hezb-e-Islami.

There will be no American presence at the meeting, according to a U.S. State Department official.

The Taliban want to speak directly with the U.S. about the planned withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan, but that clashes with Washington's long-held position that reconciliation talks need to be led by the Afghans.

“We consider the U.S. as [a] major party to the conflict, and talks could only be held with them,” Mujahid told Fox News.

[pullquote]

The Taliban is also demanding the release of five men being held by the U.S. who are also on a U.N. sanctions list.

The U.S. Department of Defense identified the Taliban prisoners as Khirullah Said Wali Khairkhwa, a senior official and major opium drug lord; Mullah Noorullah Noori, senior military commander; Abdul Haq Wasiq, Deputy Minister of Intelligence for the Taliban; Mullah Muhammad Fazl, Deputy Minister of Defense and Chief of Staff of Taliban Army; and Muhammad Nabi Omari, a senior official who served in multiple leadership roles.

But the U.S. also has made it clear the Taliban “is not in a position to make demands,” according to one senior U.S. military official.

Fox News also has learned the U.S. does not fully trust Pakistan's ability to produce the delegates for the sitdown from the highest echelons of militant groups. Among those Pakistan would be expected to produce are Mullah Omar of the Taliban and Jalaluddin Haqqani, chief of the Haqqani network, to reassure both the United States and the Afghan government they were negotiating with credible and empowered delegates.

The U.S. does not view Pakistan's recent release of Afghan prisoners as a particularly significant event, considering the men returned as mostly low-level members of militant groups. But diplomats have cautiously noted the degree of optimism with which the Afghan High Peace Council leader, Salahuddin Rabbani, returned from his visit to Pakistan in November.

Afghanistan still largely distrusts Pakistan, yet is desperate for a peace settlement as the 2014 NATO withdrawal deadline nears. The Afghans fear the Taliban could easily capitalize on the government’s limited security forces, corrupt administration, and ethnic rivalries to throw the country into civil war.

In a recent interview with Fox News, the Afghan ambassador to Pakistan said that country is key to the peace process.

“I am sure it’s now clear that violence in Afghanistan has spilled over to Pakistan and the region,” said Ambassador Omar Daudzai. “I would say that Pakistan wants a political settlement in Afghanistan that would include Taliban, but they wouldn’t want it slipping back to violence because they have learned that [harms them].”

The Afghanistan government wants to talk to what they call the “political Taliban,” described by Daudzai as those who who ruled the country as an Islamic emirate from 1996 until 2001.

Fox News sources have confirmed a “Peace Process Road Map to 2015,” drafted by the Afghan High Peace Council, proposes to award the Taliban ministerial, governor or other portfolios to share in the government, without being elected.

“They call themselves the Quetta Shura now,” says Daudzai, referring to the Taliban’s main council, rumored to be based in the southwestern Pakistani city of that name. “That’s where we expect to have a beginning of dialogue and reach a negotiated settlement.”

The reference to the Quetta Shura will raise hackles in Pakistan, which denies its existence, in line with its policy of publicly denying the Taliban leadership is based within its borders.

Dominic Di-Natale also contributed to this report.