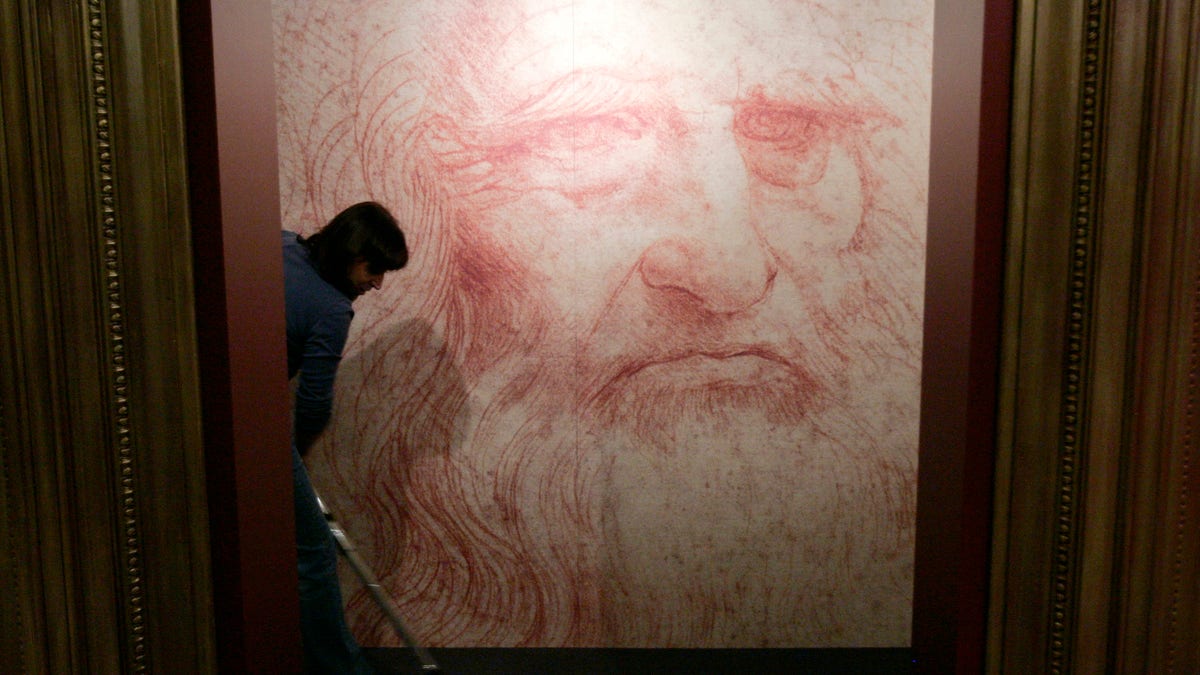

A cleaner vacuums in front of a Leonardo da Vinci self-portrait drawn around 1515 or 1516, during the inauguration of the exhibition "Leonardo da Vinci, the European Genius" in Brussels, August 17, 2007. (REUTERS/Francois Lenoir)

An international team of scientists are collaborating to gather more information about Leonardo Da Vinci and his work, trying to solve a mystery and determine if bones presumed to belong to the famed Renaissance artist are in fact his.

As part of the ambitious project, researchers are hoping to glean DNA evidence from work by the creator of the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper to see if they can match it with other genetic material.

Da Vinci, who was born in Italy but died in France in 1519, is believed to be buried in a chapel at the Château d’Amboise. But it’s not been proven that the bones thought to be his actually are.

Related: Who among us has Neanderthal, Denisovan DNA?

As one possible avenue towards solving the mystery, scientists would like to see if they can find Da Vinci’s DNA in work that he touched centuries ago. That would give them more information, and also might be a method of analyzing paintings for their veracity in general.

“It is well known that Leonardo used his fingers along with his brushes while painting, some prints of which have remained, and so it could be possible to find cells of his epidermis mixed with the colors,” Jesse Ausubel, director of the Program for the Human Environment at The Rockefeller University, wrote about the project in a special issue of the journal Human Evolution. “The Leonardo Project seeks to verify whether fingerprints obtained from Leonardo’s paintings, drawings, and notebooks can be compiled and eventually attributed to him.”

A close up shows details in the "Adoration of the Magi", a painting that Leonardo da Vinci started in 1481 at the age of 29 but abandoned a year later, as it is unveiled in Florence September 23, 2014. ((REUTERS/Max Rossi))

For example, the Da Vinci painting the Adoration of the Magi, currently being restored in Florence, Italy, is one possible source of genetic traces of the famed artist and inventor.

Related: Ancient DNA reveals bones in Spanish cave were Neanderthals

In California, the J. Craig Venter Institute, which has a long history of work on the human genome, will reportedly study the technique using other old paintings.

“The search for Leonardo’s death mask and remains at Amboise Castle, for the remains or traces of his family members in Florence, Vinci, and Milan, and for traces of his DNA in his works is fraught with difficulty,” Ausubel continued. “Matching Leonardo’s DNA to that of his family presents puzzles that are minutely specific to their history and circumstances, but the tools the investigators use are generic and broadly applicable.”

The project doesn’t just involve genetic information. Investigators have also used ground-penetrating radar at the Badia Fiorentina in Italy to learn more.

Related: DNA from mysterious 'Denisovans' helped modern humans survive

The project was launched in 2014, and investigators hope to have an answer by 2019, five centuries after Da Vinci died. It involves teams from five countries.