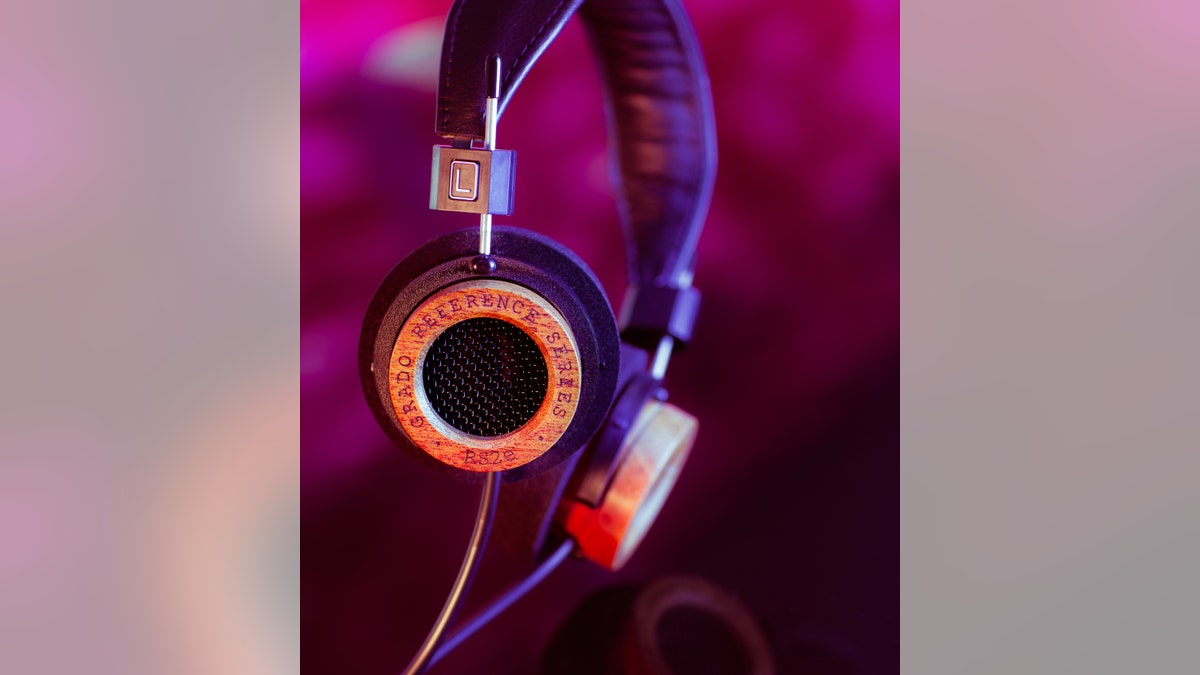

Grado headphones. (Jones Studio Limited)

If you've ever been irritated by the tinny, nasal-like quality of digital tunes, this may be the year you get relief. It's called high resolution audio (HRA) and it promises to be the anodyne for improved, high fidelity sound—even better than those dusty CDs no one listens to any more.

Several electronics companies, from boutique firms like Audioengine to behemoths like Sony, have been pushing the idea and selling hi-res compatible gear. And musicians have promoted the format, notably Neil Young who founded the PonoMusic company, which is going to offer a portable, Toblerone-shaped $399 gadget to play better music.

Although there is no official hi-res specification or format, audiophile-quality tracks typically are 24-bit, 96-kHz files (although the sample rates can be higher, say, at 192 kHz). To put the numbers in perspective, CD tracks are sampled at 16 bits and 44.1 kHz. (As for MP3s, fugetaboutit.) However, the numbers don't do justice to the auditory experience.

Listening to a hi-res track can put you in the middle of a jazz quartet, able to discern every nuance, key strike, every pluck of the stand-up bass. It can breathe new life into old songs as well. Remastered hi-res versions of Beach Boys songs make you feel as if you're sitting next to Brian Wilson in the studio. With its superior dynamic range, hi-res rock and roll has more concussive force. Moreover, classical music fans can finally appreciate composers whose arpeggios are otherwise squashed by current digital file sizes.

To join the hi-res movement, you need three things: hi-res digital files, a device that can decode the files for playback, and a decent set of speakers (or headphones).

Hi-res albums are available for purchase online at several sites. HDtracks is the most popular site in the U.S., and it offers a wide array of music from Led Zeppelin to Liszt. There's a fair selection of classical and jazz recordings, but shoppers should note that hi-res albums still command a premium price, typically $18 to $20.

You may—but you needn't—spend a lot more on equipment and gadgets that can recognize hi-res files and output them to headphones or speakers. There are standalone boxes that include music storage, such as Sony's HAP-S1 Hi-Res Music Player System. It’s basically a hi-res stereo system in a box that will store (on a 500 GB drive) and play back just about any high resolution file format. It works with a pair of headphones or conventional (unpowered) speakers. To get the music tracks onto the player, there's an Ethernet port or wireless Wi-Fi for transferring the songs you purchase. The downside is the price: $1,000. But there are less expensive alternatives.

Several thumb-sized dongles can be connected to a computer's USB port to play back hi-res files in their pristine form. These gadgets take the digital stream and do the digital-to-analog conversion independently. Often referred to as outboard DACs, models like Audioengine's D3 and AudioQuest's DragonFly cost roughly $150 or less. These devices are best for those of us who play most of our music from a laptop or desktop computer in the office or den.

Of course, just as your car is only as good as the tires you put on it, so your hi-res experience will ultimately only be as good as the headphones or speakers you use. For jazz, classical, and rock, I'm partial to headphones from Grado Labs and Sennheiser that fit over the ear; expect to pay about $350 or more for a pair that will help you appreciate the hi-res difference. Speaker choices are as varied as musical taste, but there are some notable bookshelf-sized speakers in the $300- to $400-a-pair price range including JBL's 3 Series LSR305, Sony's SS-HA1, and Pioneer's SP-BS22-LR's. All are well worth the price.

Is hi-res or HRA going to become the next music format, replacing MP3s and CDs? There are two main issues facing its wide adoption: There is no official standard HRA format, and there is no current streaming hi-res service.

Consumers will encounter an alphabet soup of file format acronyms, such as AIFF, FLAC, and DSD, although most hi-res gear supports most of the formats. The lack of a streaming solution may be more a serious roadblock to hi-res popularity, particularly since so many of us appreciate the convenience of services like Pandora and Spotify. However, one of the major players in supplying digital music to services such as rara and Sony Unlimited, Omnifone announced this week that it would support Neil Young's Ponomusic. That could turn out to be a major boost to supporting more hi-res stores. It doesn't mean there will be a hi-res streaming service tomorrow, but it's a step in the right direction.