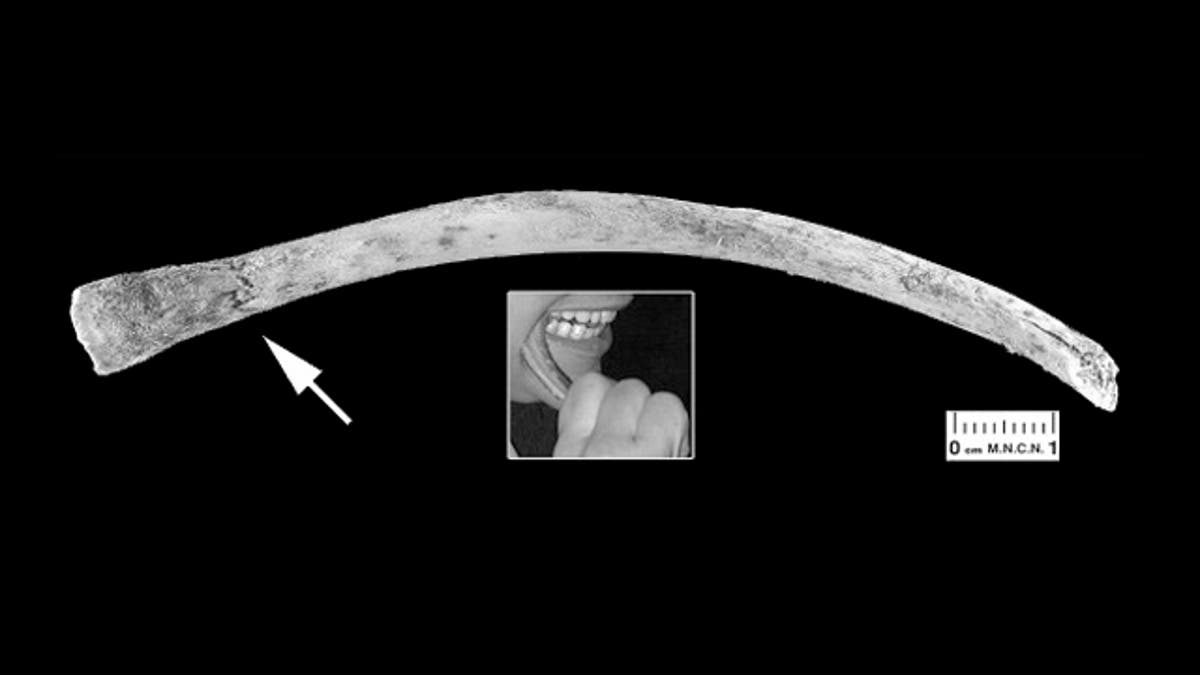

A rib fragment compressed and slightly bent at one end (white arrow) chewed by a European volunteer using the cheek teeth. The small inset shows one of the experimenters performing this action. (Y. Fernandez-Jalvo et al.)

Prehistoric humans may have gnawed on each other's bones, researchers now suggest.

Scientists have long seen evidence of prehistoric cannibalism, such as butcher marks on bones. To learn whether or not cavemen also chewed on human bones, researchers first had to get a good look at what such bite marks might look like.

Scientists had volunteers chew on bones — not human ones, but raw pork ribs and sheep legs as well as barbecued pork ribs and boiled mutton. The bone-gnawers included both Europeans and Koi people from Namibia.

The researchers saw patterns in the chewed bones — including bent, scalloped edges and surface punctures and grooves. They detected similar bite marks on 12,000-year-old bones from prehistoric humans from Gough's Cave in England and 800,000-year-old remains from the extinct human species Homo antecessor at the Gran Dolina site in Spain.

"This helps give a better idea of what was going on as the first humans were recolonizing Britain after the last ice age," said paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner at the Smithsonian Institution, who did not take part in this study. "They could've been under major stress over resources, and nutritional cannibalism may have been an adaptation for it."

Not all of these bite marks are unique to people. Still, the scientists explained that when seen in combination, they may provide evidence of human gnawing.

"It would be really interesting to see if any of the toothmarks found on the really early prehistoric assemblages of fossils were made by humans as opposed to mammalian carnivores," Pobiner told LiveScience. "Some of the earlier species of Homo would have had chewing muscles a lot more robust than ours, with a better ability to do damage to bones than we do."

The researchers detailed their findings in the January 2011 issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

- Weird Ways We Deal With the Dead

- The Many Mysteries of Neanderthals

- Top 10 Things That Make Humans Special

Copyright © 2010 LiveScience.com. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.