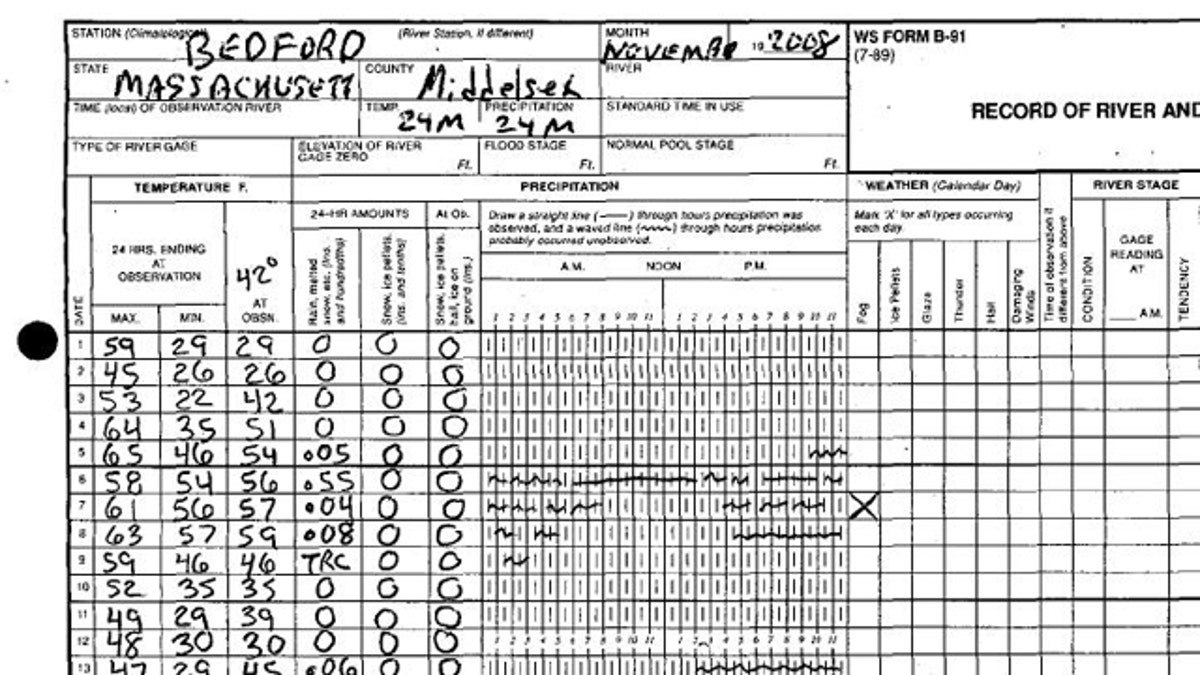

To measure weather, volunteers take readings at different times of day, round to the nearest whole number, and mark up paper forms they mail in monthly.

Crucial data on the American climate, part of the basis for proposed trillion-dollar global warming legislation, is churned out by a 120-year-old weather system that has remained mostly unchanged since Benjamin Harrison was in the White House.

The network measures surface temperature by tallying paper reports sent in by snail mail from volunteers whose data, according to critics, often resembles a hodgepodge of guesswork, mathematical interpolation and simple human error.

"It's rather archaic," said Anthony Watts, a meteorologist who since 2007 has been cataloging problems in the 1,218 weather stations that make up the Historical Climatology Network.

"When the network was put together in 1892, it was mercury thermometers and paper forms. Today it's still much the same," he said.

The network relies on volunteers in the 48 contiguous states to take daily readings of high and low temperatures and precipitation measured by sensors they keep by their homes and offices. They deliver that information to the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), which uses it to track changes in the climate.

Requirements aren't very strict for volunteers: They need a modicum of training and decent vision in at least one eye to qualify. And they're expected to take measurements seven days a week, 365 days a year.

That's a recipe for trouble, says Watts, who told FoxNews.com that less scrupulous members of the network often fail to collect the data when they go on vacation or are sick. He said one volunteer filled in missing data with local weather reports from the newspapers that stacked up while he was out of town.

Click here to see a well-filled form | Click here to see a form missing data

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. Volunteers take their readings at different times of day, then round the temperatures to the nearest whole number and mark down their measurements on paper forms they mail in monthly to the NCDC headquarters in Ashville, N.C.

"You've got this kind of a ragtag network that's reporting the numbers for our official climate readings," said Watts, who found that 90 percent of the stations violated the government's guidelines for where they may be located.

Watts believes that poor placement of temperature sensors has compromised the system's data. Though they are supposed to be situated in empty clearings, many of the stations are potentially corrupted by their proximity to heat sources, including exhaust pipes, trash-burning barrels, chimneys, barbecue grills, seas of asphalt — and even a grave.

Once the data reaches the NCDC, climate scientists in Ashville digitize the numbers and check to make sure there are no large anomalies. The introduction of electronic weather gauges into the system in the 1980s was a much-needed update, but the new and improved gauges measure temperatures slightly differently and must be corrected to sync up with the overall historic data.

If numbers appear faulty or if more than nine days are missing from a single month's tally, the whole month is thrown out, according to NCDC documents, and the Center uses a computer program to determine average temperatures at dozens of nearby stations to guess what the temperature would have been for the month at the unknown station.

The overall land temperature record produced by the NCDC is used by a number of top climate research centers, including the U.N.'s International Panel on Climate Change, NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, headed until recently by Phil Jones, who stepped down in the wake of the Climate-gate scandal.

What it boils down to, Watts says, is that some of the world's top climate scientists have been crunching numbers that were altered by their immediate surroundings, rounded by volunteers, guessed at by the NCDC if there was insufficient data, then further adjusted to correct for "biases," including the uneven times of day when measurements were taken -- all ending up with a number that is 0.6 degrees warmer than the raw data, which Watts believes is itself suspect.

But scientists at the NCDC say the system is an indispensable tool for measuring local temperatures, and that its readings are buttressed by the consensus drawn from the 8,000 surface stations that make up the Cooperative Observer Program, the overall national system of which the 1,218 stations in the Historical Climatology Network are just a part.

"We use the rest of the COOP network to help calibrate," said Jay Lawrimore, chief of the climate monitoring branch at NCDC. "It's used to do quality control."

NCDC climatologists carefully track temperature trends at local levels to ensure that the data submitted by volunteers is reliable, adjusting for the biases caused by the time of day when measurements are taken, for differences between old and new equipment, and to account for flukes that might be caused by poor siting.

The NCDC insists its adjusted numbers are an accurate representation of climatic reality, backed up by worldwide trends in air temperature, water temperature, glacier melt, plant flowering and other indicators of climate change.

"The signal appears to be robust, a reliable temperature signal," said Lawrimore.

But Watts says that even a single step — the rounding of the daily temperature — creates a margin of error about as large as the entire global warming trend scientists are hoping to confirm.

It all could become moot within a decade, as the climate center's outmoded Pony Express is currently being replaced with a screaming bullet train.

Lawrimore told FoxNews.com that about 5 percent of the historical network has already been automated, but a far more important development has been the launching of the digitally run Climate Reference Network (CRN), a system of 114 stations that went fully online in 2008.

The CRN was carefully sited in fields around the country and automatically records daily climate data and transmits it at midnight local time, sending it by satellite and eliminating the snail-mail delay, the rounding of numbers and any elements of human error.

But that doesn't mean the Historical Climate Network is going away, say NCDC scientists, who will continue to rely on its volunteers' readings to gather climate data on the local level.

So don't stable those ponies just yet.