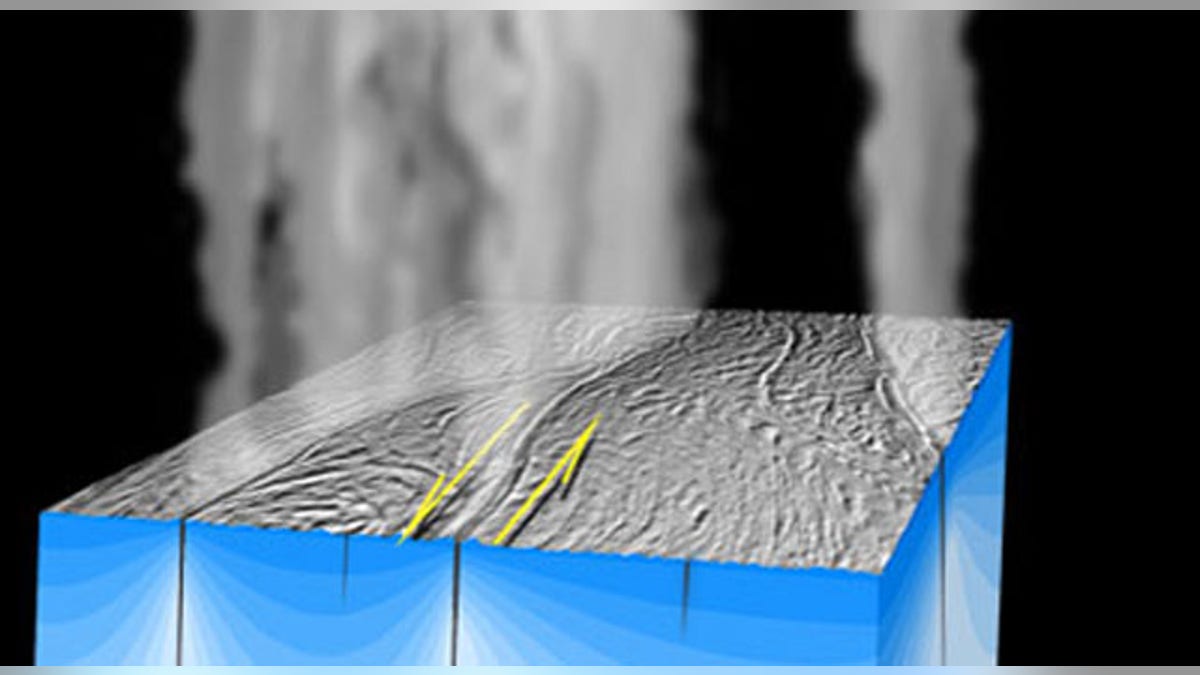

An artist's illustration showing plumes of water vapor and other gases escape at high velocity from the surface of Saturn's moon Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL (NASA)

Icy plumes of water vapor erupting from Saturn's moon Enceladus have left scientists divided over whether a liquid ocean lies hidden beneath the icy surface. Now evidence from a 2008 plume fly-through by NASA's Cassini spacecraft has turned up short-lived water ions that suggest liquid water does indeed exist inside the moon.

Negatively charged ions represent atoms that have more electrons than protons, and they seem relatively rare in the solar system. Scientists have found negative ions only on Earth, Saturn's moon Titan, the comets and now Enceladus. But negative water ions appear on Earth's surface only where ocean waves or waterfalls keep liquid water in motion — a suggestive hint of liquid water also in motion somewhere inside Enceladus.

Cassini's plasma spectrometer also turned up negatively charged ions of hydrocarbons, or compounds made entirely of hydrogen and carbon.

"While it's no surprise that there is water there, these short-lived ions are extra evidence for sub-surface water and where there's water, carbon and energy, some of the major ingredients for life are present," said Andrew Coates, a planetary scientist at the University College London and lead author on the latest Cassini study.

The measurements came from samples collected during Cassini's icy plunge into an Enceladus plume on March 12, 2008. The U.S.-European spacecraft first discovered the existence of such plumes in 2005, which shoot thousands of miles into space. Many of the icy particles and water vapor eventually escape the moon's gravity entirely and help create Saturn's huge outermost ring, called the E-ring.

Cassini's repeated dips into the icy plumes of Enceladus have fueled debate about the possibility of a salty ocean that lies hidden on Saturn's sixth largest moon. Many scientists think that the geysers not only represent good evidence of liquid water, but also mark Enceladus as a possible world for life to arise.

Still, other studies challenged the liquid ocean idea by arguing that the water vapor in the plumes could have just as easily transformed directly from solid ice, in the process known was sublimation.

The new discovery of negatively charged water ions may tilt the balance of evidence once more in favor of a liquid ocean. And at least once physicist, Brian Cox at the University of Manchester in the UK, has already handed out a wink and a nod to the group of Cassini scientists headed by Carolyn Porco.

"You always said to me that you'd find water on Enceladus :-)" wrote Cox to Porco today via Twitter.

Copyright © 2010 Space.com. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.