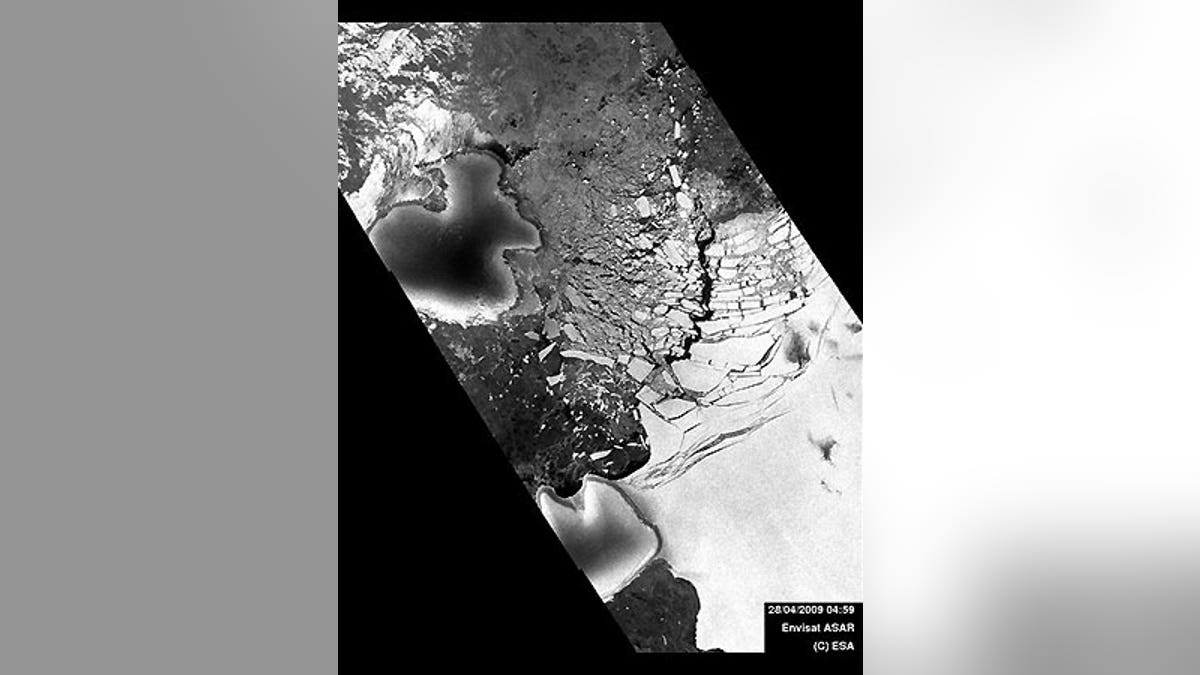

(AP/European Space Agency ESA)

WASHINGTON – New satellite information shows that ice sheets in Greenland and western Antarctica continue to shrink faster than scientists thought and in some places are already in runaway melt mode.

British scientists for the first time calculated changes in the height of the vulnerable but massive ice sheets and found them especially worse at their edges. That is where warmer water eats away from below. In some parts of Antarctica, ice sheets have been losing 30 feet a year in thickness since 2003, according to a paper published online Thursday in the journal Nature.

Some of those areas are about a mile thick, so they still have plenty of ice to burn through. But the drop in thickness is speeding up. In parts of Antarctica, the yearly rate of thinning from 2003 to 2007 is 50 percent higher than it was from 1995 to 2003.

These new measurements, based on 50 million laser readings from a NASA satellite, confirm what some of the more pessimistic scientists thought: The melting along the crucial edges of the two major ice sheets is accelerating and is in a self-feeding loop. The more the ice melts, the more water surrounds and eats away at the remaining ice.

• Click to visit FOXNews.com's Natural Science Center.

"To some extent it's a runaway effect. The question is how far will it run?" said the study's lead author Hamish Pritchard of the British Antarctic Survey. "It's more widespread than we previously thought."

The study does not answer the crucial question of how much this worsening melt will add to projections of sea level rise from man-made global warming. Some scientists have previously estimated that steady melting of the two ice sheets will add about 3 feet (1 meter), maybe more, to sea levels by the end of the century. The ice sheets are so big, however, that it probably would take hundreds of years for them to disappear.

As scientists watched ice shelves retreat or just plain collapse, some had thought the problem could slow or be temporary. The latest measurements eliminate "the most optimistic view," said Penn State University professor Richard Alley, who was not part of the study.

The research found that 81 of the 111 Greenland glaciers surveyed are thinning at an accelerating self-feeding pace.

The crucial problem is not heat in the air, but the water near the ice sheets, Pritchard said. The water is not just warmer, its circulation also is adding to the melt.

It is alarming," said Jason Box of Ohio State University, who also was not part of the study.

Worsening data, including this one, keep proving "that we're underestimating" how sensitive the ice sheets are to changes, he said.