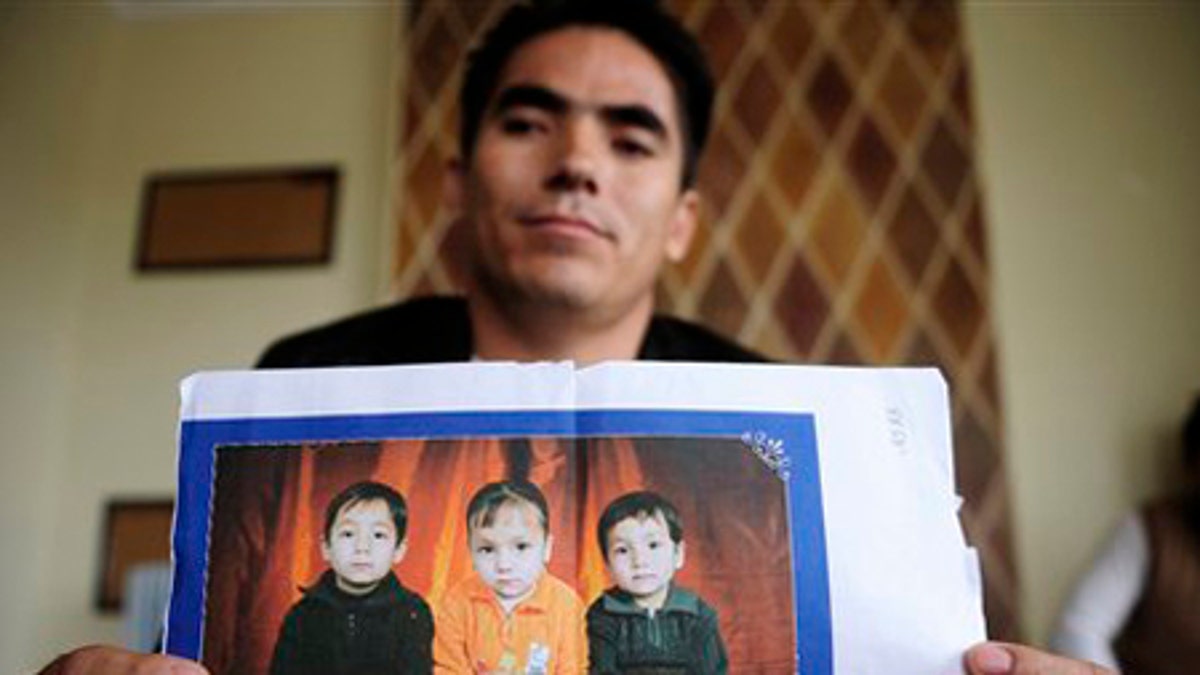

Ali Khosh Razaee holds pictures of his three young children at a house in an Adelaide, Australia, suburb. (AP)

ADELAIDE, Australia – Two years ago, Ali Khosh Razaee bought his freedom. The price he paid was his brother.

The brothers had fled Afghanistan for their lives, and a welder in neighboring Pakistan offered them a loan of $7,000 to be smuggled far from the region. The catch: To guarantee repayment — plus $2,000 interest — one of them had to stay behind to work with the man.

Muhammad volunteered.

"I didn't want to leave him but ..." Razaee trails off, his gaze far away. "We decided to save one of us. The threat was higher against me than my brother."

As violence in Afghanistan is rising, so is the exodus of refugees streaming out of the country. Razaee was among 18,500 Afghans who sought asylum in another country in 2008, fleeing war and persecution based on religion or politics, according to the United Nations. That's up 85 percent from the year before.

The danger is even greater for Hazaras like the Razaees, who belong to a Shiite Muslim minority that makes up 9 percent of Afghans. The Taliban, who are Sunni Muslim, have sought out and massacred thousands of Hazaras in Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan. So the Hazaras attempt to make their way to a third country, sometimes putting their trust in smugglers who promise to take them "somewhere safe."

"We have no choice," Razaee says. "Everything in our lives has been dangerous. At least we trust the smugglers more than we could trust the Taliban."

As the 27-year-old speaks, he looks down and picks at the carpet with his rough farmer's hands. He often wipes his fingertips across his forehead, as if trying to dismiss a painful memory. He fidgets slightly in his Western clothes, pulling on the zipper of an Adidas faux-leather jacket.

His left eye, injured in a Taliban beating, is bloodshot and unfocused.

———

Razaee used to farm wheat, barley and corn in the small central Afghan village of Abdi to feed his wife and six children.

But Razaee's father and uncle had both fought in a mountain insurgency against the Taliban. Razaee sent his family to live with his in-laws in another village. He knew trouble was coming.

In late 2007, it came. Ten thugs stormed his home, tied him up and forced him to march with his father and uncle to a town an hour away. There, the men beat them for hours with a thick, knotted rope and then left.

Razaee's father, bound hand and foot, managed to boost his son out the window. Razaee skirted the roads and ran back to his village to find his brother. They hid in the mountains.

A week later, his father's body was found.

Razaee brought his brother, mother, wife and children to a more distant town, where they lived in hiding. But they soon decided Afghanistan was not safe.

In September 2008, the brothers left their homeland, using $1,000 borrowed from Razaee's father-in-law. The only thing Razaee carried with him was a photo of his three youngest children.

The trek from central Afghanistan to the Pakistan border took five days and five nights. After bribing their way into Pakistan, the brothers crammed into a truck with 20 other people for a 12-hour ride to Quetta, on bumpy backroads to avoid checkpoints.

Razaee found a smuggler, who gave him a fake passport. The smugglers are easy to find - they are the friends of the money lender or the relatives of the pawn shop owner.

Razaee was put on a plane in Quetta and told he would be met when the flight landed.

He had never flown on a plane before. He had no idea where he was going.

———

On the plane, Razaee could not eat. He barely slept, fearful that he would miss his smuggling connection or that his false documents would be discovered.

"They told us to keep our heads down, don't be noticed," Razaee says. "If there were other refugees like me on the flight, I didn't know about it. I didn't understand any of it and didn't speak to anyone the entire time."

After at least 10 hours of flying and a stopover, he ended up in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. An Indonesian man who spoke his language, Dari, guided him through immigration into a waiting car. The dense buildings and heavy traffic gave way to green foliage. He wondered if this was it, the end of his journey.

Instead, Razaee spent the next three or four weeks living in a reed hut in the jungle with eight other Afghan men. He remembers humidity, mosquitoes — lots of mosquitoes — and a diet of instant noodles that still makes his nose crinkle in distaste. The other men told him they had been waiting for weeks.

"It was a desperate situation," he says. "I didn't know what would happen next. I didn't know if my family were safe. I didn't know where I was or if I would ever leave this hut."

The men were guarded day and night and not allowed outside. At night they could see lights in the distance through the trees. All they could do was sit on the floor of the hut and wait.

His dead father, his wife and children, his enslaved brother — it was too much to think about. So Razaee spent much of his time sleeping.

"When you're happy, you talk. None of us were happy, so ...," Razaee recalls. "We felt so hopeless. We were hopeless in Afghanistan, but we were with our families. Now we didn't even know where we were or where they were."

Finally, three months after he had left Afghanistan, Razaee boarded a small fishing boat. He was terrified. Three Indonesian crew members, 21 Afghans, nine Arabs and four Sri Lankans crowded on board, squeezed so tight they could only sit or stand. Razaee could not swim.

"We thought we wouldn't be alive much longer," he says. "This was the end of our lives."

There was barely enough food, but most were too sick to eat anyway. The boat rocked on stormy seas, and water swirled around them because of crashing waves and a leak in the hull. The healthier men took turns to bail with a bucket.

It was cold and rainy. There was no land in sight. Razaee was vomiting and feverish.

It was 10 days before an Australian Navy ship intercepted the boat, 110 miles (177 kilometers) off the northern Australian city of Darwin, on Dec. 16, 2008.

Razaee lay dazed, cold and starving on the floor of the boat.

He had never heard of Australia before he landed on Christmas Island. He was shocked when shown on a map how far he had come.

————

Afghan refugees have ended up all over the world.

More than 2 million live in neighboring Pakistan, which sees them as a burden and a security threat. About a million live in Iran, which earlier this year was accused of deporting Afghan refugees. Others have fled as far as they can go, to the United States, Canada, Europe, Brazil, Indonesia, even New Zealand.

Australia accepts 13,500 refugees every year from all over the world. But Australia does not have the resources to help them all, and those who pay smugglers and enter illegally are in less need than many others, argues Sharman Stone, a spokeswoman for Australia's opposition Liberal party.

"It's a shocking human dilemma for us and for every country that is currently receiving unlawful or unauthorized arrivals," Stone says. "It's an international dilemma."

More than 95 percent of Australia's refugees come by plane. But in the last year alone, 15 boats from Indonesia carrying 850 people were intercepted in Australian waters.

About 1,500 people are registered as refugees in Indonesia, according to the U.N. Another 1,500 are believed to be living there unregistered, in camps or crowded cities, waiting for smugglers to load them onto boats headed for Australia.

"The idea that there is some orderly queue of refugees waiting for a safe haven ... there is no such thing," says Ian Rintoul, spokesman for Australia's Refugee Action Coalition. "There are people in Indonesia who have been waiting up to nine years for refugee status. It's notoriously slow, if even possible. It's no wonder that some take the option of trying to get here by boat."

Australia has beefed up its spending on border protection, adding AU$65 million ($52 million) for more ships, aircraft and people to patrol the waters. Refugees are taken to a 1,000-bed detention center on Christmas Island, a remote Indian Ocean territory closer to Indonesia than Australia.

Former Prime Minister John Howard tried to crack down on refugees by forcing them to reapply every five years to stay in Australia and barring their families from joining them. But last year, new Prime Minister Kevin Rudd relaxed a mandatory detention policy for asylum seekers and allowed full residency visas for refugees.

Some say Rudd's policies have brought the boats back. But the government tracks the increase in refugees to increasing violence in places like Iraq, Iran, Sri Lanka and, of course, Afghanistan. In 2008, 54 Afghans applied for asylum in Australia or New Zealand.

Rafaee was one of the lucky ones.

Doctors treated him at Christmas Island. He was allowed a phone call to Pakistan, where he found his wife, mother and children had resettled. Australia approved his asylum application.

In late March he was flown to Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, where a local Afghan family took him in. He lives in a warm, comfortable house, with enough food to eat, free English classes and a government stipend. He is looking for work in a warehouse or as a driver.

But he cannot stop worrying about his wife and children, 6,000 miles (9,656 kilometers) away. Every week, he visits the migration lawyers to complete the application for his family to come to Australia.

"I don't sleep at night," he admits, staring down at the photo of his children on the floor in front of him.

He does not know if he will ever be able to pay the debt to free his 20-year-old brother.

"I think there is a 95 percent risk of losing my brother in Pakistan," he says.

The $9,000 debt was due June 30. He could not pay.

Since then, another $2,000 has been added to the balance.