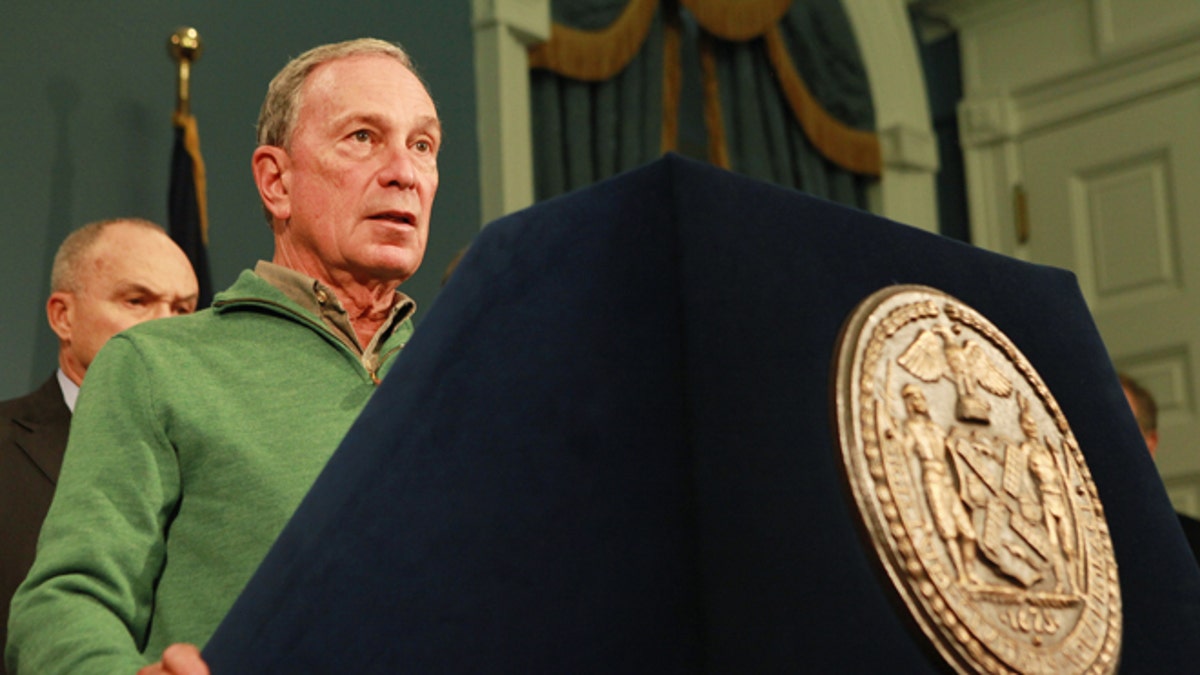

In this photo provided by New York City Mayorâs Office, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg updates the media on the Cityâs Superstorm Sandy recovery efforts, Friday, Nov. 2, 2012 in New York. Later that day Bloomberg Bloomberg cancelled the 2012 New York Marathon amid growing public pressure. (AP Photo/NYC Mayorâs Office, Kristin Artz)

Sports history is filled with controversial calls.

The decision to cancel Sunday’s New York City Marathon in the wake of Hurricane Sandy will not go down as one of those.

Word came Friday evening that the annual 26.2-mile, five-borough race was officially off, ending the outrage that had been snowballing as race preparations got underway.

In an ESPN.com poll with nearly 115,000 respondents, 83 percent of the voters agreed with the decision. A “Cancel the 2012 NYC Marathon” Facebook page garnered more than 50,000 likes in two days.

The cancellation announcement was made just hours after Mayor Michael Bloomberg had defended the decision to hold the marathon, even as many residents in New York City and neighboring New Jersey were still reeling from the effects of the storm.

Millions of residents remain without power. Tens of thousands of families continue to sift through their flooded damaged homes, or worse, what is left of their homes. Lines for gas snake around blocks as people wait hours for fuel. The death toll hit the triple digits

Assurances that the marathon would not take away resources from the storm cleanup efforts weren’t enough.

I feel pretty strongly about [postponing the race]...I love the marathon and have now done five, including NYC. But not now, it’s too soon.

There were the reports that displaced families who have no homes to go back to were being booted from hotel rooms to make way for the throng of racers descending upon the city less than a week after the superstorm wrecked havoc on the East Coast.

Huge generators powering media tents in Central Park, when some homes and businesses remain dark, sparked a backlash and seemed the ultimate image of insensitivity.

Turning the prerace party into a free meal for anyone displaced by the storm as race organizers planned was putting a (well-meaning) Band-Aid on a broken leg.

“I feel pretty strongly about [postponing the race],” Toni Beninato said shortly before the cancellation came down. “I love the marathon and have now done five, including NYC. But not now, it’s too soon.”

Beninato, who lives in Manhattan, is originally from nearby Sayreville, N.J. In Sayreville, residents were being rescued from their roofs as the storm hit. Much of the town, including Beninato’s family home, is still without power.

So is much of Staten Island, where the NYC marathon starts. Ferry service has only just resumed, and the borough suffered extensive damage in the storm. Of the 41 recorded storm-related deaths in New York City, 19 were in Staten Island.

Bloomberg had touted the marathon as an image of the city’s resolve, its ability to bounce back in the face of adversity, a bright spot in such a dark time.

Sporting events have done just that before, transcending competition to mean something more. Major League Baseball’s return to New York City in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks provided moving, poignant moments.

But the decision to soldier on with competition too soon after tragedy also can cast a shadow. The International Olympic Committee’s efforts to carry on with the 1972 Munich Games during and after the hostage crisis and massacre were protested then and still are criticized generations later. Pete Rozelle said the NFL’s decision to play a full schedule just days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was his biggest regret as league commissioner. Given the public outcry, had this year’s marathon taken place, the race seemed destined to join this list.

Usually sporting events are about winners, but this story has none. As with so many stories surrounding the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, the narrative is just about varying levels of loss.