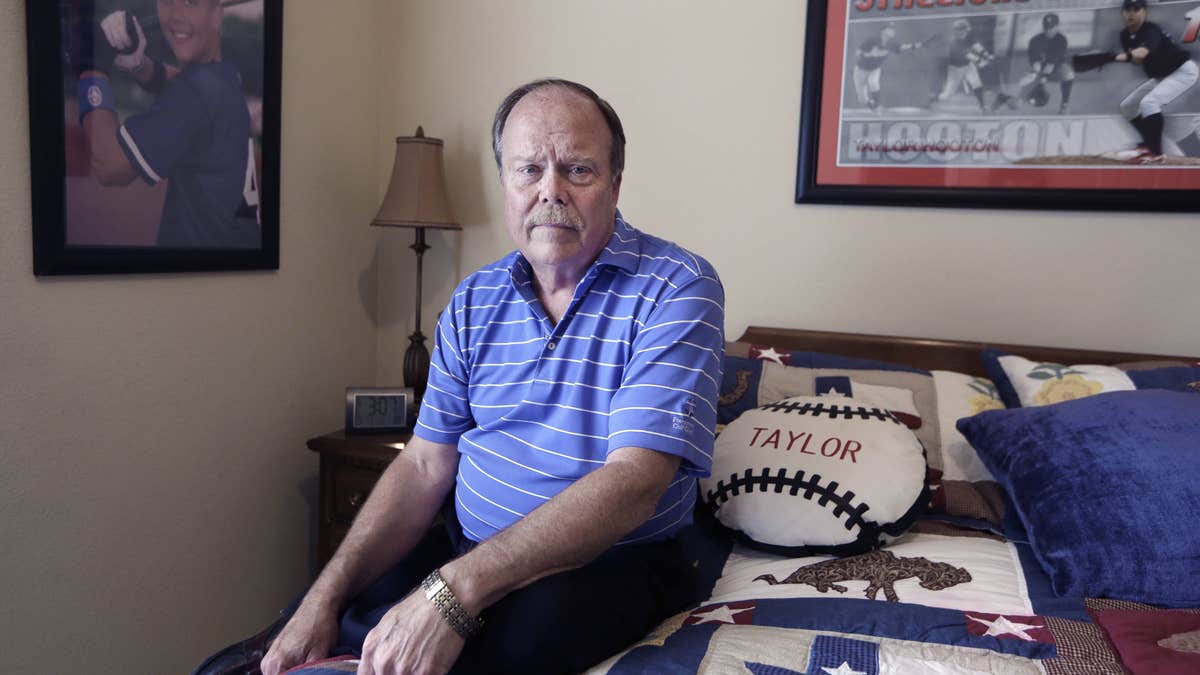

March 17, 2015: Don Hooton posses for a photo in a room with remembrances of his late son Taylor Hooton at his home. (AP)

Texas is ready to defund its statewide public high school steroids testing program this summer leaving two other states with similar testing models.

Created in 2007, state officials feared every student-athlete was going to use performance-enhancing drugs; from football players to tennis athletes. Now, eight years after spending $10 million to catch a handful of cheating students out of a possible 63,000, some call the program a colossal misfire.

"I believe we made a huge mistake," said Don Hooton, who started the Taylor Hooton Foundation for steroid abuse education after his 17-year-old son's 2003 suicide was linked to the drug's use, and was one of the key advocates in creating the Texas program.

Hooton does not believe the low amount of positive tests among high school athletes means that a majority of them are clean. He thinks they are not getting caught because loopholes allow them to cheat the process.

Abandoning testing will leave New Jersey and Illinois as the only state’s with such a program. New Jersey and Florida were the first states to start the program, but Florida dumped its testing in 2009. New Jersey and Illinois spend about $100,000 annually testing just a handful of athletes.

Texas had pumped millions to scour the state for cheaters. A positive test would suspend an athlete for 30 days. The state immediately was questioned over the amount of money that was dumped into its program.

Schools across the country closely watched Texas, said Don Colgate, director of sports and sports medicine at the National Federation of State High School Associations.

"Texas was going out in front in a big way," Colgate said. "(But) it's not a cheap process and they knew there were not going to do it on the scale of what Texas did."

Although the state governing body of high school athletics, the University Interscholastic League, conducted a survey in 2002 that revealed schools wanted testing to be a local decision, steroid-filled sports headlines prodded the state to forge ahead with its multi-million dollar program.

Texas hired Drug Free Sport, which conducts testing for the NCAA, the NFL, Major League Baseball and the NBA, to randomly select students, pull them out of class and have them supply a urine sample. The first 19,000 tests produced just nine confirmed cases of steroid use, with another 60 "protocol violations" for skipping the test.

Lawmakers saw those numbers as kindling for criticism instead of reassurance that its young athletes were clean. Texas only tested for 10 drugs in the first examinations, only a fraction of the anabolic agents on the market.

Students had eye-opening loopholes when it came to testing. Testers had to tell school officials when to be on campus and were not allowed to physically watch the person provide a urine sample.

The testing protocols, including which drugs were tested for, were developed by the UIL and Drug Free Sport.

"The program they developed was bound to fail," Catlin said. "I told them years ago to put the money into something else."

State lawmakers have been scaling down the Texas program almost since it began. It trimmed to $2 million by 2010 and then less than one million after that.

The number of positive tests have lowered after fewer athletes were tested. The UIL only caught two cheaters out of 2,633 tests in the 2013-14 school year.

Hooton said those low figures don't match anecdotal evidence of higher steroid use among teens. A 2014 study by the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids found that 7 percent of high schoolers reported using steroids from 2009-2013.

The Texas Sunset Advisory Commission, which reviews state programs, recommended in 2014 that lawmakers drop the program. The commission's report noted that unless the state wanted to pump up to $5 million a year into a program on par with elite college and pro leagues, it wouldn't be effective either in catching cheaters or scaring them away from drugs.

The Associated Press contributed to this report