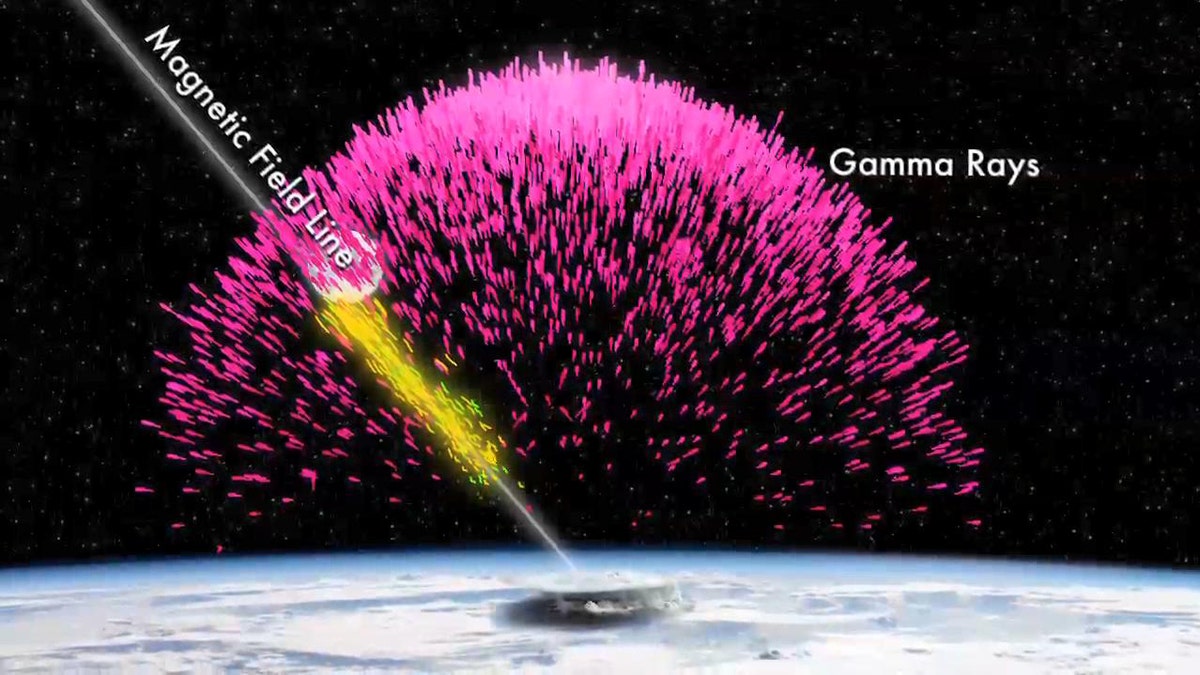

NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has detected beams of antimatter launched by thunderstorms. (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/J. Dwyer/Florida Inst. of Technology)

Thunderstorms create far more than just rain. NASA has accidentally discovered that they spit out antimatter, too.

Scientists using the space agency's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope have detected beams of antimatter produced above thunderstorms on Earth, a phenomenon never seen before. They believe the antimatter particles were formed during "terrestrial gamma-ray flashes," sharp bursts produced daily inside thunderstorms that are still poorly understood.

Thunderstorms are known to create supercharged electric fields, of course, as evidenced by lightning. But the creation of antimatter is something else.

"These signals are the first direct evidence that thunderstorms make antimatter particle beams," said Michael Briggs, a member of Fermi's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor team at the University of Alabama in Huntsville.

Scientists long have suspected that these terrestrial gamma-ray flashes (TGFs) arise from the strong electric fields near the tops of thunderstorms. Under the right conditions, they say, the field becomes strong enough that it drives an upward avalanche of electrons. Reaching speeds nearly as fast as light, the high-energy electrons give off gamma rays when they're deflected by air molecules.

Normally, these gamma rays are detected as a TGF. But the cascading electrons produce so many gamma rays that they blast electrons and positrons clear out of the atmosphere. This happens when the gamma-ray energy transforms into a pair of particles: an electron and a positron. It's these particles that reach Fermi's orbit in space.

Fermi is designed to monitor gamma rays, the highest energy form of light. When antimatter striking Fermi collides with a particle of normal matter, both particles immediately are annihilated and transformed into gamma rays. Now Fermi has detected gamma rays with energies of over half a million electron volts, a signal indicating an electron has met its antimatter counterpart, a positron.

"In orbit for less than three years, the Fermi mission has proven to be an amazing tool to probe the universe. Now we learn that it can discover mysteries much, much closer to home," said Ilana Harrus, Fermi program scientist at NASA headquarters in Washington.

"The Fermi results put us a step closer to understanding how TGFs work," said Steven Cummer at Duke University. "We still have to figure out what is special about these storms and the precise role lightning plays in the process."