(Adam Huttenlocker)

Pacino has some pint-sized competition. Researchers have recently unveiled a newly discovered pre-mammal species named Ichibengops munyamadziensis — “Scarface of the Munyamadzi River.” The dachshund–sized prehistoric carnivore, which may have been venomous and lived 255 million years ago, earned this moniker from the groove on its upper jaw.

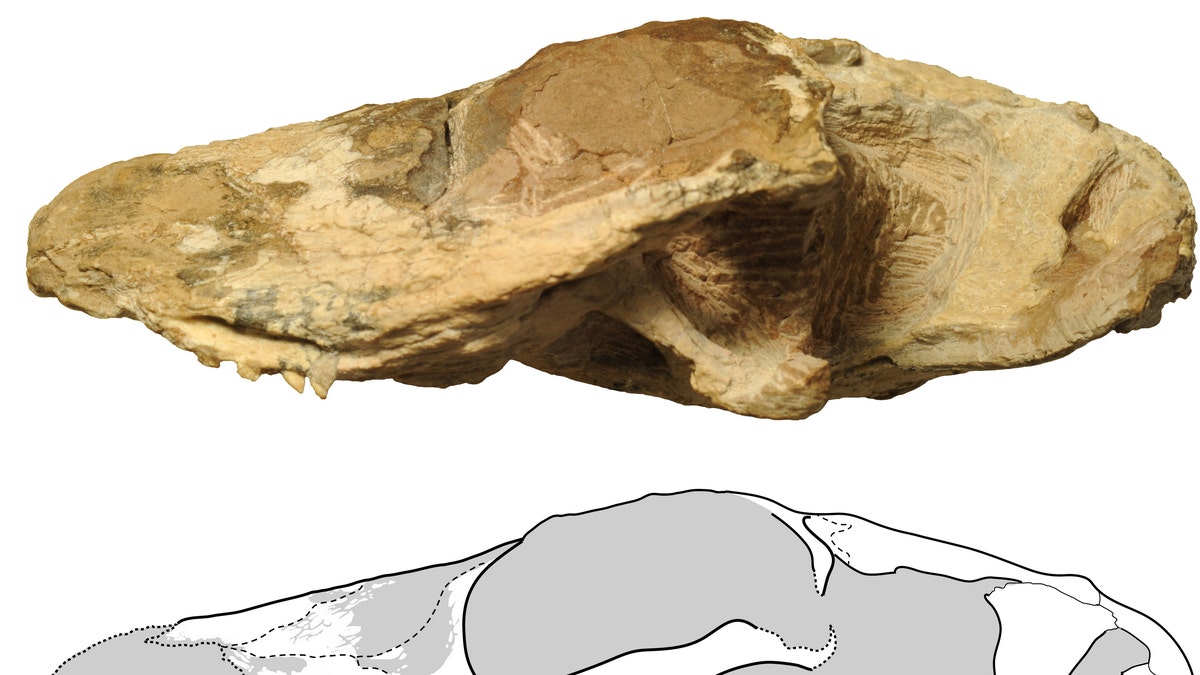

The partial skulls were discovered in Zambia in 2009, according to a release from the Field Museum in Chicago.

“They were found on the surface of rock outcrops we were prospecting for fossils,” said Kenneth Angielczyk, study co–author and associate curator of paleomammalogy at the Field Museum. “They had already undergone some weathering, which is reflected by the fact that neither specimen is complete.”

Of course, Angielczyk’s team didn’t realize that the skulls they found were from a new species of therocephalian (venomous, carnivorous mammal–like reptiles from the Permian and Triassic periods) until well after they were unearthed.

“In the time since discovery the specimens have been prepared (i.e., extra rock was removed to expose more of the specimen itself), and this allowed us to make detailed comparisons of the anatomy of Ichibengops to other therocephalians,” Angielczyk told Foxnews.com. “Doing this showed that the two specimens share anatomical features (like the groove on the face) that are not found in other therocephalians, which is consistent with the specimens representing a previously unknown species.”

Ichibengops had furrows above its teeth, which may have been indicative of venom–delivering capabilities. Venomous mammals are rare, with the duck–billed platypus and certain shrew species being the only examples living today. Angielczyk added that Scarface may have been venomous due to its similarities to another therocephalian called Euchambersia.

“Euchambersia has very distinct, large pits on the side of its face that connect to grooves on the canine teeth via a groove above the tooth row,” he said. “This combination of features in Euchambersia has been used to hypothesize that it may have been venomous, although again we can't be completely certain of this. The groove in Ichibengops shows some similarities to that in Euchambersia, and because they are fairly closely related, we suggested that something similar may have been going on in Ichibengops.”

He also noted that until more complete specimens are discovered — particularly ones with canine teeth preserved to see if grooves are present — it can’t be said whether the creature was venomous or not, and even then it would be hard to establish definitively.

Angielczyk and his team do a lot of their fieldwork in Zambia, Tanzania, and South Africa, where a very good fossil record of land animals from the Permian and Triassic are preserved.

“The rocks [there] produce a lot of fossils, and the fossils themselves are often quite well preserved, so they are very useful in our studies,” he explained.

The overarching framework for his team’s research in Zambia is to gain insight into how animal communities (like Ichibengops’) on land were affected by the Permian-Triassic mass extinction, which was the largest mass extinction in Earth history, he said.

With global warming an important causal factor in that extinction, it has a definite relevance to the world today.

“One way we're investigating this problem is to look at the food web structures of communities before and after this time, in part to see how they changed as a result of the extinction and subsequent recovery, but also to see if the food web structures of some communities may have helped make them more or less resistant to the environmental disturbances that were going on,” Angielczyk added. “Discovering new members of the communities we're studying, like Ichibengops, helps us to model the communities and their responses as accurately and in as much detail as possible, which in turn helps us have confidence that are model results are accurate. We can use these results to help make predictions about what communities today might be especially vulnerable to disturbances, as well as the way they might respond.”

The study can be found in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.