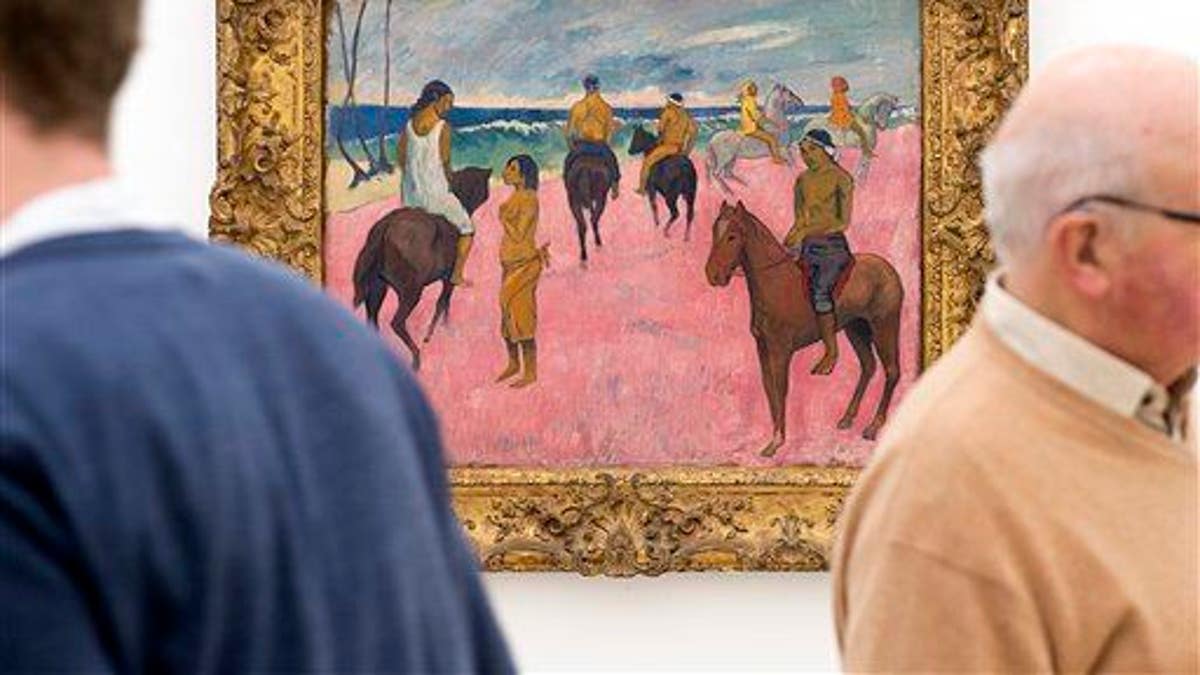

Two men stand next to "Cavaliers sur la plage" (Riders on the beach, 1902) by French painter Paul Gauguin at an exhibition in the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen, Switzerland, on Friday, Feb. 6, 2015. (AP Photo/Keystone,Georgios Kefalas)

The French artist Paul Gauguin may be best known for his paintings—one of which sold just this month for $300 million, one of the highest prices ever paid for a work of art—but the printmaking he worked on toward the end of his life in the early 1900s is turning out to be so complicated and experimental that art conservators are "blown away" by the new findings, reports Northwestern University.

Computer scientist Oliver S. Cossairt, who announced the findings in San Jose over the weekend, worked with art conservation specialists at the Art Institute of Chicago to reveal Gauguin's surprising techniques, including layering, transferring, and re-using imagery.

Since September, the team has been analyzing 19 of the artist's prints at the Art Institute—the most in-depth analysis being of the work "Nativity (Mother and Child Surrounded by Five Figures)," completed in 1902 a year before Gauguin's death—using a process that dates back to the 1980s called photometric stereo.

It entails taking a sequence of photos from a fixed camera while light on the subject jumps to a new position. Software then helps separate out color from surface shape to detail the paper's topography.

Cossairt tells Newsweek the process is "simple" but still "labor intensive," with 20 million pixels processed for each print. One finding: Gauguin made white lines by drawing on an ink surface, thereby removing the ink, and transferred the resulting lines to the print.

(Check out why one woman attacked a Gauguin painting in Washington's National Gallery.)

This article originally appeared on Newser: Scientists 'Blown Away' by Gaugin's Art Techniques

More From Newser