McConnell fulfills promise, Senate opens immigration debate

Can an open-ended debate on immigration reform produce a bipartisan bill in the Senate? Democratic commentator Monique Pressley and syndicated radio host Kevin McCullough join the debate.

The Senate perhaps failed this week to advance any of its immigration-border security plans because of the order in which members voted on the four proposals.

Pitchers and catchers are now in Arizona and Florida for spring training. And even in Cactus and Grapefruit League games, the batting order means a lot in baseball.

A speedy guy with a high on-base percentage hits first. Someone who makes contact a lot bats second. The “RBI” men bat third, fourth and fifth. The light-hitting folks just north of the Mendoza line bat seventh and eighth. In the National League, pitchers hit ninth.

But what if the rules were tilted so that in a clutch situation, the home team required the visitors to bring up their worst hitters? What if the rules dictated that when home team had its best hitters coming to the plate in the bottom of the ninth that the visitors had to summon their worst reliever from the bullpen?

It doesn’t work that way in baseball. Everyone bats in the same order, regardless of circumstances, unless there’s a pinch-hitter.

There’s a typical batting order in the Senate, too. And while it may be advantageous to some to alter the lineup depending on the “game” situation, it’s not really practical and doesn’t align with Senate custom.

That may be why the Senate failed to advance any plan this week on immigration, DACA and border security.

The senate majority leader is the “first among equals.” It’s Senate tradition to yield to the leader, who’s first to speak on the floor, sets the schedule, determines what issues are in play and sets up the voting order.

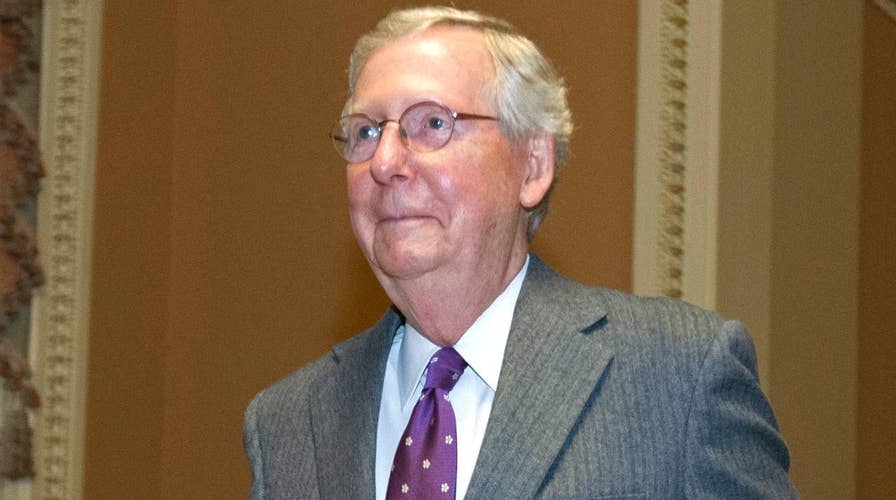

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., arranged an agreement with all 100 senators Thursday afternoon to take procedural votes on four amendments.

Each required 60 to end debate. The primary amendment was a border security/DACA/immigration measure backed by President Trump, pushed by conservatives and drafted by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa.

Next was a bipartisan approach written mainly by Sens. Mike Rounds, R-S.D., and Angus King, Independent-Maine, and facilitated by Susan Collins, R-Maine. Then there was an initiative by Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Pa., to bar sanctuary cities from receiving federal assistance.

Finally, there was a DREAM Act/border security measure written by Sens. John McCain, R-Ariz., and Chris Coons, D-Del.

The so-called DREAM Act would provide permanent, legal protections for immgrants brought to the U.S illegally by their parents.

The are temporarily protected by the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program that Trump is ending.

Congressional Republicans are also trying improve federal immigration policy, particularly ending immigration programs based on family ties or a lottery that they argue pose security risks.

The Senate usually votes on amendments in reverse. So McCain/Coons was first, followed by Toomey, then Rounds/King and finally, Grassley. McConnell made it clear he supported the Grassley effort. And since McConnell is majority leader, he made the Grassley amendment the “baseline” for the immigration/DACA debate.

But this is where things get interesting.

On Wednesday night, multiple sources indicated that the voting sequence could be key to advance any measure. In other words, the Senate may need a good power hitter at the plate at just the right moment. Or perhaps the leadoff man capable of swiping a base or two.

The Rounds/King bipartisan package was slotted as the third of four votes in the Senate queue. And since the plan was bipartisan, it’s no surprise that amendment scored the most votes: 54. But it needed 60 to break a filibuster. The fourth-and-final vote was the conservative, partisan plan pushed by McConnell and President Trump.

In a stunning rebuke, that measure commanded a meager 39 yeas. In fact 60 senators voted against ending debate on that effort. It takes 60 yeas to quash a filibuster or “invoke cloture” in the Senate. Sixty nays is like invoking reverse cloture. In fact, just moments before the roll call tally, Grassley told senators in a floor speech that his amendment “is the only plan that can become law because the president supports it.”

And then Grassley got clocked.

It’s typical for the majority leader to favor the baseline or “preferred” piece of legislation, perhaps slotting it in the final-vote position. But multiple sources on both sides of the aisle argued that the Senate may have had a better chance at kissing 60 yeas to break a filibuster had leaders rejiggered the sequence so that the bipartisan measure went last.

Such a maneuver wouldn’t have been unprecedented. But it would have been rare and perhaps tricky parliamentarily.

The bipartisan package had the most votes. So if it’s the final vote, some senators believe they could have persuaded a few more of their colleagues to vote yes. After all, it’s a “bipartisan” effort. And it was the last-ditch effort to do something on immigration and DACA. No other amendment marshaled 60 yeas. Senators would realize the impasse would continue. That’s why some suggest that senators who weren’t originally enamored with the bipartisan package may have accepted something less than perfect and voted yes.

By the same token, Senate sources argue that the sequencing may have condemned the Grassley plan to receive the fewest votes. By its nature, the final vote was on a conservative amendment. It was likely to only court Republicans -- though three Democrats voted yes: Sens. Joe Donnelly, of Indiana; Joe Manchin, of West Virginia; and Heidi Heitkamp, of North Dakota.

All are moderate Democrats facing competitive re-elections this fall in states Trump won in 2016. A staggering 13 Republican senators voted nay, rejecting the wishes of the president. It’s possible the number of no votes ballooned because senators realized the gig was up and nothing could hit 60.

So Republicans voted nay, not only because they disliked the conservative plan, but because some realized the impasse would continue. It wasn’t worth voting yes on something doomed to fail. That may have helped suppress the vote total on the Grassley package.

That said, there were a lot of factors working against the bipartisan measure.

Just before the vote, Sen. Tom Cotton -- an Arkansas Republican and ardent supporter of the Grassley measure -- decried the bipartisan initiative as the “olly olly oxen free amendment.”

Perhaps. But it may have encountered a different fate with a different vote structure.

But just like in baseball, the Senate can’t change the lineup just to receive a desired outcome. Bringing up the number three batter when the number seven batter is due at the plate. And it’s not even clear that everyone wanted an outcome on immigration, DACA and border security.

Teams substitute on the fly in football, basketball and hockey to get the best matchup they can against an opponent. But in baseball, batting order remains the same unless there are pinch-hitters, pinch-runners and double-switches. In baseball, you accept the matchup as it comes. And the same is true in the U.S. Senate.