Confederate Monuments Removed: What happened to them?

Many Confederate monuments and flags have recently been removed from public places in the South. Where are those Civil War symbols now

A revived campaign to remove Confederate statues and symbols from government grounds has reignited an impassioned national debate pitting opponents against self-described "patriots" who argue the monuments stand for heritage and not hate.

These tensions were bared over the weekend when defenders of those symbols traveled to Gettysburg, Pa., preparing to face off against rumored anti-Confederate protests.

Those protests never materialized.

But while the Confederate flag remains a deeply offensive symbol to many Americans and a painful reminder of the South's history of slavery, some -- like those who came to Gettysburg -- say flying the flag is about preserving heritage and honoring ancestors.

“It makes me want to cry,” Pat Roller of Pasadena, Md., told Fox News in front of the North Carolina monument at Gettysburg National Military Park. “I have ancestry on both sides.”

Roller, who said she takes photos for the Sons of Confederate Veterans, said she doesn’t know why there’s so much uproar over Civil War symbols of the South.

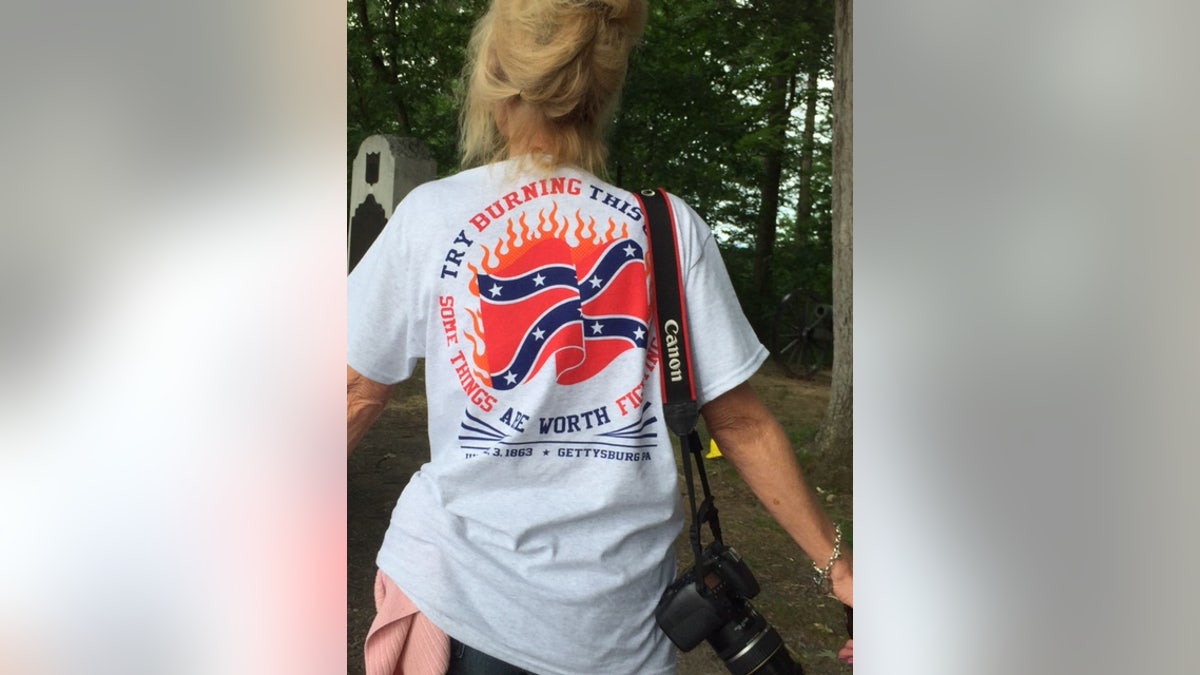

Roller -- wearing a white t-shirt with a Confederate flag on it that read “Try burning this. Some things are worth fighting for” -- says it makes her “a little angry” that people say Confederate symbols preach racism to kids.

But that’s the exact argument being made by those pushing for monument removal.

“I don’t want my kids to think this is normal or that these men are heroes,” Dana Simpson, a mother of three who lives in a suburb outside of Atlanta, told Fox News.

Simpson grew up in the South and said the flag debate hits close to home.

“There are people in my immediate family who are fierce supporters of the flag. It’s a tough and emotional issue for everyone,” she said. “Hell, my husband was for it too… but the tide’s turning.”

The campaign to pull back Confederate symbols began decades ago – but back then, it was mostly talk.

That all changed June 17, 2015 when 21-year-old Dylann Roof opened fire in a historically black church in Charleston, S.C. –- murdering nine people who were there for a bible study. Roof later confessed he committed the crime in hopes of igniting a race war.

Pictures and video quickly surfaced of Roof spitting on and burning the American flag while posing for pictures and waving the Confederate flag.

The momentum and backlash from the horrific shootings prompted then-Gov. Nikki Haley to order the removal of the Dixie flag from statehouse grounds.

“My hope is that by removing a symbol that divides us, we can move forward as a state in harmony and we can honor the nine blessed souls who are now in heaven,” Haley announced.

Since then, at least 60 public Confederate symbols have been removed since the 2015 church shooting, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Most recently, the city of St. Louis, Mo., removed a Confedearte monument -- a 32-foot-tall granite column with a bronze sculpture -- from a park.

Complicating the debate for those opposed to these moves is the involvement of hate groups like the KKK. The group is planning a rally for July 8 following a decision by the city council in Charlottesville, Va., to remove a statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee and rename Lee Park.

Meanwhile, in April, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu ordered the removal of multiple Confederate statues. Landrieu received brutal backlash and was forced to have heavy police presence in place when the nighttime removals began.

Despite threats that people would boycott New Orleans, Landrieu did not back down.

"These statues are not just stone and metal," he said in a highly lauded speech after the last Confederate statue had been taken down. "They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement and the terror that it actually stood for."

But to others, like Hanceville, Ala., Mayor Kenneth Nail, it’s not about oppression.

"To us, it’s not a hate thing. It’s a heritage thing and what we like to do is celebrate everyone's struggles: the blacks, the whites, the north and south,” Nail told The Cullman Times.

Nail recently wrote to Landrieu asking him to consider donating the discarded monuments to the Veterans Memorial Park in Hanceville, which is about 40 miles north of Birmingham.

"One of my good friends, who is black, even messaged me on Facebook and told me, 'Look, some of my ancestors were forced to fight in that war (the Civil War), and I think it's a good idea to remember these things.' He told me, 'I drive a truck, and I'll even go down there and pick them up if the city needs me to,'" Nail said.

There’s no word on whether Landrieu took him up on the offer.

Calls to Landrieu's office were not immediately returned.