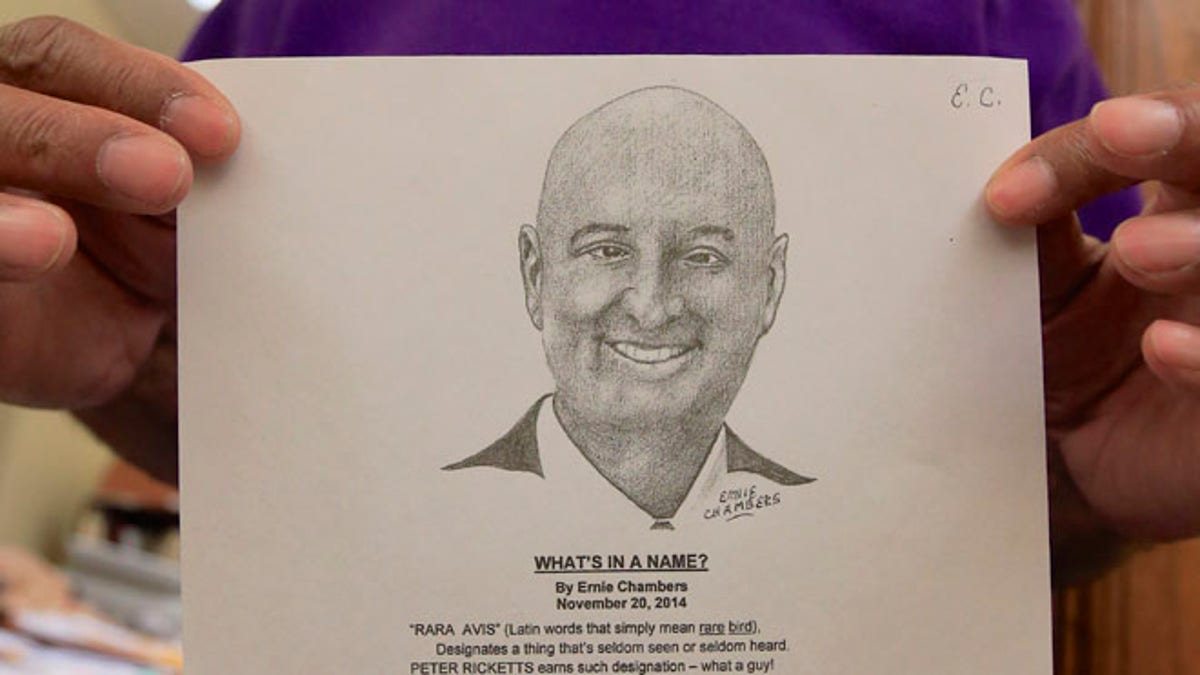

March 18, 2015: Nebraska State Sen. Ernie Chambers of Omaha holds in his Lincoln, Neb., office a portrait and poem he made of Neb. Gov. Pete Ricketts. (AP)

Nebraska's longest-serving lawmaker drops to one knee and spreads more than five-dozen sheets of notepaper across the floor of his office.

Sen. Ernie Chambers points to pencil sketches of a man, a pig and a hairy Cyclops. Behind him sits a box of framed portraits, created with a childhood skill he's quietly honed during a 40-year legislative career. Between drawn-out committee hearings and floor debates, Chambers has built a sketch-art portfolio featuring everyone from Malcolm X to Gov. Pete Ricketts.

"It's therapeutic," said Chambers, 77. "I watch the pencil and things just flow out of it -- words that rhyme and pictures that shade themselves. Sometimes, I'm not even concentrating on making a picture. I'm just putting lines on a sheet of paper."

His fellow lawmakers have taken notice -- and even asked for copies of some of the work.

Chambers, of Omaha, served 38 years in Nebraska's one-house Legislature before voters enacted term limits that forced him from office. The self-described "Defender of the Downtrodden" was elected again in 2012 after sitting out the minimum time required. He's legendary for his repeated attempts to abolish the death penalty, his knack for derailing legislation he opposes and the sweatshirts and jeans he wears at the Capitol amid others' suits and ties. In 2007, the left-leaning independent sued God to make a point about frivolous lawsuits.

Chambers said he doodles in committee hearings to fight boredom when familiar issues arise. In the first 45 days of this year's session, he scrawled more than 60 images on sheets the size of a hotel notepad.

He captions his drawings with random thoughts. Beneath his Cyclops, Chambers wrote: "Man, oh, man. I can't wait for evolution to kick in! Things can only get better!!!"

When Omaha attorney Dave Domina spoke this month in a hearing related to the Keystone XL pipeline, he wasn't just testifying: He was unknowingly posing for a portrait. As Domina argued for tougher regulations on oil pipelines -- a bill Chambers introduced -- Chambers' pen gave shape to a slender face, suit and glasses.

Chambers tends to draw in committee hearings when the side he favors is testifying, said Sen. Adam Morfeld of Lincoln, who serves with him on the Judiciary Committee. When his adversaries speak, Chambers puts down the pen and peppers them with questions.

Morfeld said he was amazed by the quality of art, which Chambers sometimes combines with poetry and distributes to lawmakers. "I've thought about asking him for one or two," Morfeld said. "I call them Ernie-grams."

Sen. Bob Krist of Omaha noticed Chambers pencil-sketching a human eye earlier this year. The picture had such depth that Krist asked for a copy to show his wife, an oil painter.

"He's a great multitasker," Krist said. "He sits there and draws, but he's always listening to every word of the arguments."

Chambers said he started drawing in high-school art classes and continued through law school. A law professor noticed his work on a piece of poster board and suggested Chambers pursue a career as an artist. "In my mind, he was telling me anything he could to get me out of his school," Chambers said.

His collection features portraits of John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and a smiling young mother with her infant son. His 2001 rendition of Elvis Presley was so detailed that a Capitol staffer framed it and hung it in her office. Other sketches are more political or function as social commentary, such as Joe Camel with skull and a pack of cigarettes.

Despite the praise, Chambers insists he's not an artist but a "drawer," because he lacks formal training.

"What I do is like Burger King: Have it your way," he said. "If some people see it as good art, that's what it is. If people see it as bad art, that's what it is."