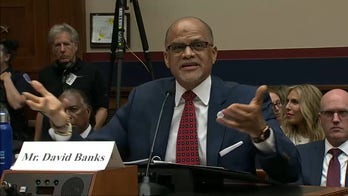

FILE: Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn speaks at a news conference in Chicago. (AP)

Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn's decision to halt legislators' pay over the state's unprecedented pension crisis is unconstitutional and the Chicago Democrat must move to reinstate salaries immediately, a judge ruled Thursday.

Illinois Comptroller Judy Baar Topinka, whose office is responsible for issuing paychecks to lawmakers, said after the ruling that she had instructed her staff to begin doing so immediately. But Quinn said he planned to appeal to a higher court and would seek a stay of Thursday's ruling.

Cook County Circuit Court Judge Neil Cohen issued his eight-page decision in a lawsuit brought by Chicago Democrats, House Speaker Michael Madigan and Senate President John Cullerton. Lawmakers have missed two paychecks and were set to miss a third next week.

Cohen said Quinn did not have the power to withhold pay while lawmakers were serving their current terms and ordered Topinka to restore salaries with interest.

"(The) Illinois Constitution grants the governor authority to reduce items of appropriation," Cohen wrote. "The governor cannot, however, exercise his authority in a manner which violates another constitutional provision."

Quinn said the issue was about more than his constitutional authority.

"The reason I suspended legislative paychecks in the first place -- and refused to accept my own -- is because Illinois taxpayers can't afford an endless cycle of promises, excuses, delays and inertia on the most critical challenge of our time," he said in a statement. "Nobody in Springfield should get paid until the pension reform job gets done."

Illinois' public pension systems are the worst-funded of any state in the nation, largely because legislators for years did not make their full annual payments. This year, that payment is about $6 billion -- almost one-fifth of the state's general fund budget and an amount that has led to substantial cuts in areas such as education and public safety.

Yet lawmakers have been unable to come up with a fix. After they adjourned the most recent legislative session without reaching an agreement, Quinn called on them get the job done and threatened unnamed "consequences" if they didn't do so. In June, legislators voted to form a bipartisan conference committee to try to hammer out a deal. When the group didn't act quickly enough, Quinn announced he was cutting $13.8 million for their pay.

In July, Quinn used his line-item veto to cut money for legislators' salaries from the state budget because they hadn't fixed Illinois' nearly $100 billion pension crisis, the worst in the nation.

But Madigan and Cullerton contended Quinn's actions were unconstitutional and violated the state's separations of powers.

Cullerton said Thursday that the judge's decision "vindicated" the constitution.

"Now that the governor's actions have been answered by a court, I trust that we can put aside all distractions and focus on the goal of pension reform," Cullerton said. "Pension reform remains our top priority. Even while this case was pending, the legislature never stopped working on this issue."

Madigan's spokesman Steve Brown declined to comment until the issue, including the stay, was resolved.

Last week, Cohen heard arguments in court where Madigan and Cullerton's attorney, Richard Prendergast, called Quinn's veto "an unprecedented attempt" to fulfill his goals through coercion.

Quinn said he had the authority to veto the salaries and that the lawsuit was premature. Quinn has said that if legislators want to be paid, they could return to Springfield and vote to override the veto -- a move Quinn has acknowledged could be unpopular with voters.

Lawmakers make an annual base salary of about $67,000, plus bonuses for serving in leadership.

Meanwhile, the bipartisan conference committee has continued to meet. It's considering a framework that would end automatic cost-of-living increases for workers and retirees. Any proposal must be approved by both chambers of the Legislature, where consensus has been difficult. Public employee unions already have said they oppose the framework.