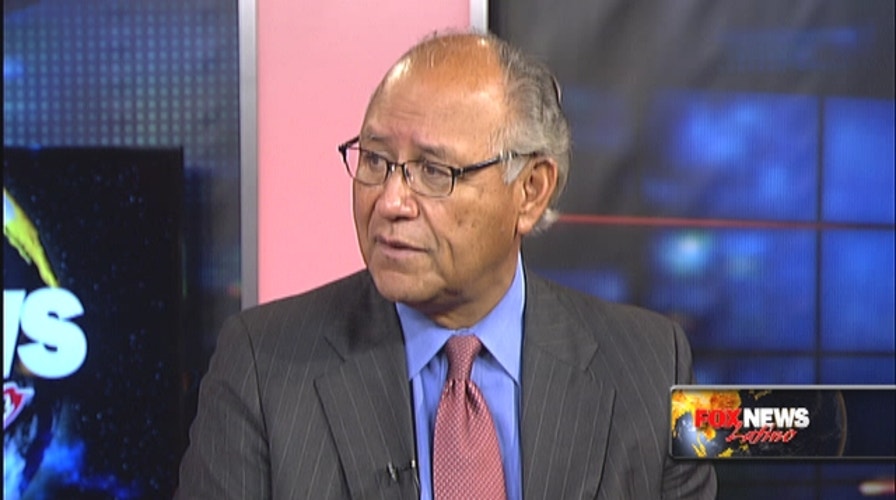

Fernando Chavez, Son of Cesar On His Father

Fernando Chavez talks to Fox News Latino about his father Cesar and his legacy.

Twenty years ago Tuesday, Cesar Chavez, called by many the greatest Latino civil rights activist of all times, died at the age of 66.

He devoted much of his life to fighting for fair wages and humane working conditions for Latino workers – making great strides, but also raising awareness of problems that, to be sure, still persist to some degree.

Now, many of Chavez’s children and grandchildren continue the fight – working for farm workers’ rights, for the children of migrant workers, for comprehensive immigration reform, for a stop to use of the word “illegal” to describe undocumented immigrants.

The way his eldest son, Fernando Chavez, puts it, there are still manifold problems facing immigrants and workers that demand attention.

“With respect to migrant workers and farm workers, even though things have gotten better, they haven’t gotten a whole lot better,” he told Fox News Latino in an interview Tuesday. “There are still many places in the country where people work for below minimum wage. There are places in this country where people live in exploitative conditions. There is still a lot of abuse.”

Chavez, a 62-year-old trial attorney, had a ring-side seat to his father’s activism in California from the time he was tall enough to reach a doorknob. He and his siblings often went along with their dad to rallies and protests, and helped make signs that would be displayed at demonstrations.

Though many of the burning issues of the day were similar to those that are grabbing headlines today, the public views and sympathies were quite different then. In fact, even Cesar Chavez, who was born in Arizona, and the union he co-founded, United Farm Workers, had their misgivings about undocumented immigrants, and were concerned they would undermine working opportunities, jobs and conditions for Latino workers who were legally in the United States.

Cesar Chavez was masterful at mobilizing masses. He employed potent tactics, such as boycotts. One boycott led 12 percent of the country’s population to stop buying grapes for seven years starting in the late 1960’s. Later, Chavez as well as many union groups became more accommodating of undocumented immigrants, seeing them as a source of new members to alleviate the declining numbers joining unions.

Cesar Chavez is said to have come up with the slogan “Sí se puede,” or “Yes, we can,” which became a battle cry for the 2008 campaign of President Barack Obama.

In his role as attorney, Fernando Chavez combines his judicial work with activism – representing immigrant workers facing wage and hour problems, injuries on the job, and substandard working conditions.

Now, working with United Farm Workers, Chavez pushes for immigration reform, believing that the United States must find a way to provide a pathway to legalization for the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the country.

“UFW is playing a very active role” in pushing for the immigration system to be revamped, he said. “No one is going to get everything they want, but it’s going to be something both labor and the agricultural industry, the two main groups forming the legislation, can support.”

“It makes sense to help them legalize their status,” Chavez said. “If they’re active in contributing to the economy here, they put money into taxes, into the Social Security system that they never get back.”

Part of his quest these days is getting news organizations to follow in the footsteps of the Associated Press and stop using the term “illegal” and “alien” to refer to immigrants without documents.

On Tuesday, he was scheduled to deliver a petition, one of the key authors of which was his mother, Helen, asking The New York Times to stop using “illegal.”

Fernando Chavez said his son, Alejandro, urged Helen Chavez to draft the petition, which has gotten 80,000 signatures.

The effort met with some success.

Though senior Times editors are not prohibiting the term "illegal immigrant," they did announce after the protest by Chavez and other activists that they would encourage their reporters and editors "consider alternatives when appropriate to explain the specific circumstances of the person in question, or to focus on actions," according to a report in the newspaper.

Later, Chavez said he pleased with the newspaper's move.

"We are encouraged by the New York Times' announcement that it will urge reporters to use terms other than 'illegal' to describe individuals who have overstayed their visas or entered the United States without documentation," he said. "Describing human beings as 'illegal' is inappropriate and degrading. We will watch closely to see whether reporters take this recommendation to heart, or whether further action is needed."

In the interview with Fox News Latino, Fernando Chavez said his son, Alejandro, reminds him of his father.

“He’s very committed to social activism,” he said.

What was it like to grow up calling Cesar Chavez Dad?

“That was my life since I could remember,” he said. “That was just my way of life.”

"I never really looked at it from that perspective," he said, referring to being the son of a legend. "He was my dad, and I had the same issues every son has with his father — conflict resolution, 'Clean your room,' 'What are you going to do with your life.'"

Many years later, he said, he got to truly understand his father stature in history.

"It's quite incredible," he said. "He was definitely more than a labor leader. He was a civil rights leader. He didn't get the notoriety that Martin Luther King got, but what he did was as important and as significant, not only for Latinos but for all working individuals."

“His life was devoted to his cause,” Chavez said. “Nothing was more important than this."