It took a mugging at gunpoint last year to push Gabriela Villafaña-Cardoso to decide, once and for all, to leave her native hometown of Toluca in Mexico.

Her mother-in-law offered a solution: “Baltimore.”

“She had seen a story on the Internet that said the mayor of Baltimore was welcoming immigrants, inviting them to make the city home,” Cardoso, 25, said. “So we decided to plan a future in Baltimore.”

Cardoso and her new groom, Oscar, joined thousands of Latino immigrants – most of them Mexican – who have settled in Baltimore in the last decade, attracted by plentiful work, an expanding Latino support system and, last year, an official invitation by Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

For Baltimore, the invitation that persuaded Cardoso to settle there was, quite simply, a matter of survival.

Like many other places around the country, Baltimore was losing people.

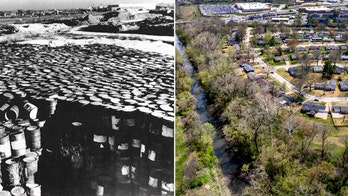

Its population dropped from nearly a million in the 1950’s to about 620,000 in 2010, the latest census showed. Homes and stores in many areas of the city were boarded up; schools were losing enrollment.

Only two other major cities in the nation were losing more people than Baltimore – Detroit and Cleveland.

One group was bucking the trend – immigrants, most of them Latino. Hispanics, in fact, doubled their numbers, from 11,000 in 2000 to 26,000 in 2010. They helped stem the double-digit population decline the city had seen in previous decades, reducing the drop between 2000 and 2010 to about 4 percent – the smallest rate in a long time.

“There was an abundance of jobs,” said Nicolas Ramos, a Mexican native who settled in Baltimore in the 1990’s after living and working in several other states. “Especially for many immigrants like myself, looking for jobs in things like construction, landscaping, handyman work, there were more jobs than available workers.”

“We wanted to solidify the city’s history as an immigrant city. It’s a younger population. They have kids, which helps school enrollment, and that’s all part of planning the city’s future. We want them to stay here and be the nurses and doctors in the city.

The answer to reversing the population decline in Baltimore was as clear as the state's Chesapeake Bay – more Latinos, more immigrants.

“When we saw that data, we said ‘O.K., there are clearly people who are coming to work and live and start businesses, so we need to do something to encourage this,” said Ian Brennan, a spokesman for Rawlings. “When people call home, we want them to say ‘Hey, Baltimore is a great place to live, it’s getting better.’”

After Assaults on Immigrants, a Move to Create Trust in Police

But there were problems and concerns among Baltimore’s Hispanics that threatened the city’s ability to continue drawing them.

In the summer of 2010, five Honduran men were attacked; two fatally. The attacks, Latino community activists said, appeared to be hate crimes. In at least one of the killings, the perpetrator, an African-American, called the victim “a dirty Mexican,” according to published reports.

And many immigrants were not turning to police about crimes they had witnessed, or of which they were victims, community leaders and city officials say.

The reluctance was rooted in the fear that turning to police would land them, or someone they cared about, in deportation. Many states, such as Arizona, had passed or were considering laws to crack down on illegal immigration; those laws mainly called for police to check the immigration status of people they stopped for another reason.

What’s more, Latino leaders say, Baltimore police were stopping Latino motorists for such things as broken headlights and not using signals and reporting them to immigration officials.

“We told the mayor that we didn’t want Baltimore to be Arizona,” said Juan Carlos Crespo Beltran, a 42-year-old auto body worker who came from Mexico 13 years ago. “We didn’t want a Sheriff Arpaio here in Baltimore.”

Rawlings, who was filling the unexpired term of Mayor Sheila Dixon, who resigned after being convicted for embezzlement, promised Latino leaders that she would take steps to address their concerns if she got elected. She won the election in 2011, with the help of Latinos who campaigned for her.

In early 2012, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, kicked into gear its controversial Secure Communities program in Baltimore, requiring local police and jail officials to send fingerprints of people who are arrested to the FBI so that it could send them to ICE.

Shortly after, with pressure mounting from Latino leaders and advocates for the city to address the fear in the immigrant community about going to police, Rawlings made a bold move. She signed an executive order, which Latino leaders helped draft, forbidding all city agencies, including the police department, from asking about immigration status.

“Police are working to make our city safe,” Rawlings told reporters. “We are not working as immigration agents.”

Speaking at the Enoch Pratt Free Library through an interpreter to a crowd of mostly Latino immigrants who greeted her entrance with applause and cries of “Sí se puede,” Rawlings said: “This new executive order will make clear that all victims and witnesses of crimes should feel safe reporting crime to city police officers regardless of their immigration status.”

Then she went a step further. She laid out a welcome mat for immigrants, saying that she hoped that they would help the city gain 10,000 more new residents in the next decade.

“Building or growing a city, especially in tough economic times, is not something the government can do alone,” Rawlings told reporters. “Baltimore’s Latino residents are hard-working small business owners and strong community leaders who are contributing to our city’s growth and prosperity.”

The outreach includes city-run classes in Spanish, training for police that covers cultural differences and the different documents immigrants carry, working with Mexican consulate officials to help immigrants with their questions, helping entrepreneurs obtain grants, among other programs that are still in the planning stages. And the city also is forming a task force that will focus on what the city can do to better serve immigrants, Brennan said.

“We delivered for the mayor, we Latinos helped get her in office,” said Beltran. “And she’s delivering for us.”

But Baltimore has an edge that other cities and states trying to attract Latinos do not – a robust Latino support system.

It is an unofficial universe of mostly Latino-run social service agencies, business owners who remember what it was like to be a newcomer, and immigrants still planting roots who advocate for the community and help address a vast array of needs and concerns among the city’s Latinos.

A Latino Support System Offers Guidance on Jobs, IRS Forms and Pet Care

Octaviano Salvador was flustered.

The 68-year-old Guatemalan immigrant had received a letter from the Internal Revenue Service telling him he owed money.

“I always get money back,” he said. “I don’t understand this.”

Salvador did not go to a tax preparer, or to an IRS office, or any other government agency with his dilemma. He went to the Esperanza Center, in one of Baltimore’s Latino enclaves, which is run by Catholic Charities and has been a refuge, friend and advocate for immigrants for decades.

The center offers the city’s immigrants everything from English classes and primary healthcare to dental work and legal help.

“I always come here for help,” Salvador said. “They explain things, they interpret notices I get in English, they help you find solutions.”

Behind the front counter at the Esperanza Center, which is located on Broadway, where business and agency signs are in English and Spanish, Jermin Laviera fielded calls about everything from immigration paperwork to traffic tickets to veterinarians.

“People come to us about all kinds of things,” said Francisco Plasencia, outreach manager for Esperanza. “Translations, immunizations, they need advice about paying their bills, they ask ‘Why are they taking more taxes out of my paycheck,’ and we end up explaining the whole fiscal cliff to them.”

Several of the workers at Esperanza recall arriving in Baltimore much like the people they help today – a newcomer with a mix of excitement, confusion and anxiety about an unfamiliar land, language and culture.

Many of the workers and volunteers at social service organizations around the city, indeed, are Latinos who walked the tough road of the immigrant, and now are beacons for the newly uprooted. At Casa de Maryland’s Baltimore office, staffers provide immigrants with ID cards, naturalization classes and help with applying for tax payer identification numbers. In various locations, Casa de Maryland also has day laborer hiring sites.

“I call consulates, police, hospitals, you name it,” said Laviera, a Venezuelan native who came to Baltimore 26 years ago, when the sound of Spanish turned heads and she had to travel 20 minutes to a Filipino supermarket for beans and plantains. “People show up here because they decided to come to Baltimore and were told to come to Esperanza for guidance. They even walk through the door with their suitcases and children, without having a place to stay.”

After Rawlings extended an invitation to immigrants to make Baltimore their home, people from around the United States and the world called Esperanza Center to ask about the city.

“I was answering calls from people in Europe and Africa,” said Laviera, 54. “I was getting calls from undocumented immigrants in other states who thought the welcome included a green card, shelter, food and a job. We told city officials that they had to clarify that that is not what they were advertising.”

Latinos who have lived in Baltimore for a decade or two say the growth they’ve witnessed in their ethnic community still amazes them.

“When my husband and I came, you hardly saw Latinos,” Laviera said. “You’d go to a store and hear Spanish and say ‘They’re speaking Spanish!’”

Cardoso, who fled the violence in Mexico, said what she agonized over most as she planned to come to Baltimore was being in a place where she did not know the language. Cardoso had never been outside Mexico.

But her husband, who came to Baltimore on a tourist visa several months before she did, told her that would not be an issue in the city.

“He told me there was a vibrant Latino community here, and that it would have a familiar feel for me,” she said. “He told me ‘Gabriela, you will be surprised and pleased.’ He was right.”

Cardoso and her husband turned to Esperanza for help in navigating the city and their adopted homeland. He is working in a pizzeria. Cardoso, who has a degree in communications from a Mexican university, volunteers at Esperanza while she pursues permanent U.S. residency.

“I hope to stay here,” she said. “In Mexico, I could not travel, even to work, by myself because it was so dangerous. Even getting on a bus is not safe there because criminals will board it and mug everyone on it and sometimes rape the women. Here I feel safe. I move around with a peace of mind that is just unthinkable back home.”

In other rooms at Esperanza, Latinos are working on their English skills.

In one room, immigrants from Peru, El Salvador, Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras sit before computers, listening to Rosetta Stone tapes and repeating the words on the screen aloud.

In an adjacent room, a young immigrant from Mexico sits with a compatriot who has been in the United States 17 years and is tutoring him in English.

Gabriel Moreno, a construction worker, said he lived in different states, including Florida and Georgia, before ending up in Baltimore and deciding to settle there.

On disability after injuring his back, Moreno spends his time volunteering, helping new immigrants learn English and participating in the Meals on Wheels program.

“I can stay productive this way,” he said. “And I can help the community.”

“You don’t feel the hostility here that you can feel against immigrants, against Latinos, in places like Arizona, Georgia, even parts of Florida,” he said.

Latinos Find Hope and Support, but also Rejection

Other Latinos, however, say they have encountered discrimination in the city, and in the less diverse areas of Maryland.

Beltran said that while going door to door to encourage residents to attend a rally in Washington D.C. in favor of immigration reform, a non-Latino man complained about Latinos.

“He said he worked in construction, and that too many Mexicans were moving into that industry,” he said. “He said ‘You people are the ones who take our jobs.’”

State legislator Patrick McDonough, a Republican from Baltimore County, assailed Rawlings for telling city employees not to check immigration status. McDonough said Rawlings was “aiding and abetting” undocumented immigrants.

He said she put Baltimore in the position of attracting illegal workers who would take jobs away from legal residents.

Brennan, the mayor’s spokesman, dismissed the criticism, calling McDonough “our local xenophobe.”

“He rails against Hispanics, blacks, gays.”

In January, the Carroll County Board of Commissioners voted to make English the official language after heated debates over whether the move was aimed at saving money – as proponents had maintained – or whether they were trying to send a “Keep Out” message to immigrants. Latinos are a small part of the county’s population of about 167,000, but at 4,400 they are the county’s fastest-growing immigrant group.

Two other Maryland counties, mostly white and Republican, like Carroll, have Official English measures.

“Historically, Baltimore has not been the most racially welcoming kind of place,” said Father Robert Wojtek, known as “Padre Roberto” in the Latino community. “You hear people say things, lump the Latinos together, refer to them all as ‘those Mexicans.’”

Wojtek said much of the negative views of Latinos and immigrants are the result of “not understanding” them.

From Building Big Homes to Owning Them

Immigrants account for about 45,000 of Baltimore’s 620,000 residents. That is more than double the number of foreign-born people who lived in the city two decades ago. Latinos make up the largest chunk – at least 40 percent. Asians, Middle Easterners and Africans make up the rest.

“We want them to come and stay here,” said Elizabeth Alex, director of the Baltimore office of CASA de Maryland, a non-profit organization that advocates for immigrant rights. “We wanted to solidify the city’s history as an immigrant city.”

“It’s a younger population,” said Alex, who played a key role in crafting the city’s executive order. “They have kids, which helps school enrollment, and that’s all part of planning the city’s future. We want them to stay here and be the nurses and doctors in the city.”

Now, the Latino community in Baltimore has role models – success stories to guide and, they hope, inspire those starting out on the lowest rungs.

They are a key piece of the unofficial support system that is helping to attract Latinos to Baltimore, and in ways both direct and indirect, make them feel welcome and at home in the city.

Nicolas Ramos is an example.

Ramos, 54, traces his days in the United States to his teen years, when he came to do seasonal farm work. Eventually he stayed, illegally, to do more regular work to send more money to his family back home in Mexico.

He finally got legal status after the 1986 amnesty, and years later arrived in Baltimore, drawn by the abundance of construction jobs.

Often, he would come home after an 18-hour day of toiling and tell his wife, Tania, that he could not believe how much perfectly usable construction materials were simply discarded. But with the proverbial immigrant optimism, he vowed to take others’ unwanted construction debris and build his own restaurant one day, with his very own hands.

“I cried,” said Tania, 42. “I thought he was crazy.”

But he did it, painstakingly renovating a boarded-up restaurant every day for four years, working on it after putting in a whole day in his regular construction job.

Nearly every brick, every table, the floors, the light fixtures in his restaurant, Arco, were discarded materials, he said.

Looking down Broadway, Ramos recalled the way the thoroughfare used to be.

“Most of these stores were boarded up about 10 years ago,” he said, “then Latinos came here and, like me, started opening up businesses. Latinos came with their families. When you come with your spouse, with your children, you care more about your community, you feel more vested. You want the schools to be good.”

Today, Ramos is one of many business owners in Baltimore who is active in pushing for improvements for Latinos in the city. He sits on Hispanic commissions in the city and the state.

“Now there are established people in our community,” Tania said, “there are people who have succeeded and can connect the dots – they can direct energy and attention to the needs of the community, they can push for change, pick up the phone and connect one person to another who can help them.”

Ramos, along with his two oldest kids – two teenage daughters – has attended meetings with city and state officials to discuss Latino needs and concerns, and has participated in rallies and marches to push for laws that would allow undocumented students to attend college at rates for state residents, and allow undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses.

Last year, voters in Maryland approved the in-state tuition measure, becoming the first state to do so by popular vote.

“It’s not just the city of Baltimore that is responding to immigrants, but the state also,” Ramos said. “Our next fight is about driver’s licenses.”