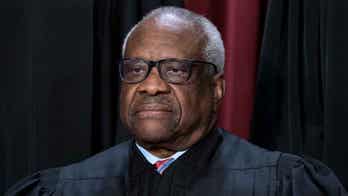

Dec. 18, 2012: A truck driver watches as a freight container, right, is lowered at the Port of Boston. (AP)

As if Superstorm Sandy and the looming fiscal crisis weren't enough, a potential strike by thousands of dock workers from Boston to Houston threatens to shock the economy as early as this weekend.

Business groups and state officials in recent days have called on President Obama to intervene, and use emergency powers to "avoid a coast wide port shutdown." They warn it could cost billions, citing estimates that a 10-day port lockout in 2002 cost $1 billion a day -- and caused a major backlog in shipments.

Florida Gov. Rick Scott is the latest to enter the fray and call for White House intervention. But a port strike would affect more than the East and Gulf coasts, where all these ports are located. It could choke supply chains across the country. Groups ranging from the automobile industry to the National Retail Federation to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to the Cheese Importers Association of America are warning of dire consequences.

"Failure to reach an agreement resulting in a coast wide shutdown will have serious economy-wide impacts," those and dozens of other groups wrote to Obama last week. They said "just the threat of a shutdown" has forced many businesses to enact costly "contingency plans."

At issue is a labor dispute between the International Longshoremen's Association, which represents dock workers, and the U.S. Maritime Alliance, which represents port operators and shipping companies.

Talks between the dock workers and the shipping companies broke down Dec. 18, just weeks after a critical West Coast port complex was crippled by a strike involving a few hundred workers.

Federal mediators have since called a meeting before the end of the week, in hopes of resolving the disagreement before the Dec. 29 expiration of the dock workers' latest contract extension.

The union could strike after that date without a resolution.

The disagreement has worried scores of business groups because of the sheer number of workers and ports involved. The union represents 14,500 workers at more than a dozen ports extending south from Boston and handling 95 percent of all containerized shipments from Maine to Texas, about 110 million tons' worth.

The New York-New Jersey ports handle the most cargo on the East Coast, valued at $208 billion last year. The other ports that would be affected by a strike are Boston; Delaware River; Baltimore; Hampton Roads, Va.; Wilmington, N.C.; Charleston, S.C.; Savannah, Ga.; Jacksonville, Fla.; Port Everglades, Fla.; Miami; Tampa, Fla.; Mobile, Ala.; New Orleans; and Houston.

Florida Gov. Scott recently wrote a letter to Obama warning of the "devastating" impact a strike would have on his state, where cargo-related activity "generates more than 550,000 direct and indirect jobs." He also recalled how, in 2002, "tons of perishable cargo were destroyed" in the West Coast lockout.

He, along with groups like the National Retail Federation, want Obama to use his powers under the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act to try and prevent a strike.

The National Retail Federation has called on the president to "use all means necessary" to avert the closure of ports.

The White House did not say whether Obama would get personally involved, but made clear they are monitoring.

"Federal mediators are assisting with the negotiations, and we continue to monitor the situation closely and urge the parties to continue their work at the negotiating table to get a deal done as quickly as possible," White House spokesman Matt Lehrich said in a statement to Fox News.

The dispute and threatened strike come at a particularly vulnerable time for the U.S. economy. Roughly $110 billion in spending cuts are set to take effect starting in January if Congress cannot come up with an alternative plan. On top of that are more than $500 billion in scheduled tax hikes, which Washington also has not yet been able to reduce.

In the dock worker labor talks, issues including wages are unresolved, but the key sticking point is container royalties, which are payments to union workers based on cargo weight.

Port operators and shipping companies want to cap the royalties at last year's levels. They say the royalties have morphed into a huge expense unrelated to their original purpose and amount to a bonus averaging $15,500 a year for East Coast workers already earning more than $50 an hour.

The longshoremen's union says the payments are an important supplemental wage, not a bonus.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.