First black Marines receive Congressional Gold Medal

The significance of the Montford Point Marines

The Army's Buffalo Soldiers and the Air Force's Tuskegee Airmen, or Red Tails, have had their day of recognition. Wednesday the Montford Point Marines had theirs, as the Marine Corps and Congress honored 400 of the first black Marines by giving them the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation's highest civilian honor.

"This is something we didn't think we'd see in our lifetime," said 1st Sgt. William McDowell, as he received the medals on behalf of the group. He started to cry, remembering those pioneering Marines, who are no longer alive to receive this honor. He then caught himself and laughed, "My commander would have said "suck it up, Marine."

Seventy years ago when these black Marines enlisted, there were still Jim Crow laws in the South. It was 1942 and the height of World War II. President Franklin Roosevelt had ordered the military to enlist blacks the year before. The Marines were the last service to do so.

"When we got off the bus, we had a rude awakening," recalled Montford Point Marine Cpl. James Pack in an interview with Fox News. "I said, "Lord, what did I get myself into?"

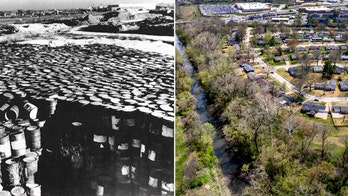

The black Marines, many of them arriving from the North, were taken to a segregated -- separate section of Camp LeJeune, N.C., for basic training.

"We knew we were being trained harder," said Lt. Col. Joseph H. Carpenter, in a Marine video made about the surviving Montford Point Marines. "They're going to make us a model to all the other white Marines. Think about it. In fact, we were breaking every record they ever had because they pushed us to the end of endurance where we just couldn't go any further."

The first recruits had to clear five and a half acres of land with their own hands at Montford Point next to the camp where whites were trained on the New River.

"Mosquitoes, rattlesnakes, bears and alligators were at that camp," Robert Hammond, one of the Marines, recalled before receiving his Congressional Gold Medal.

Marine Commandant Gen. James Amos, who pushed that these Marines finally be recognized and that Marine histories be rewritten to include their stories, described the discrimination faced by these pioneers.

"Once you crossed the Mason Dixon line," Amos told Fox News, in an exclusive interview. "They were put back, or actually put up, in a coal car, which is right behind the locomotive and that's where they stayed until they arrived in Jacksonville, North Carolina."

At first they were only allowed to provide supplies on the front lines.

"There was a reluctance to put them right in the heat of the battle so for the first little bit they were on the fringes of the battle and they would run ammunition out to the front lines to places like Pelelieu, and eventually Iwo Jima. They would bring back white Marines, who were wounded."

Eventually, they fought side by side with those white Marines when those iconic battles turned tough. Later they broke barriers together back home.

"Only when we left the camp did we feel the sting of discrimination," said former Montford Point Marine Ambassador Theodore Britton Jr. "When the white drivers in Jacksonville refused to take us back to camp, it was white Marines who commandeered the buses [at gunpoint] and drove us back to camp."

One famous former Montford Point Marine became New York City Mayor: David Dinkins.

Many of the 20,000 Montford Point Marines who trained from 1942- 49 have already died. Some are more than 100 years old.

"It's a great honor," said Cpl. Pack, as he started to cry.

For the 400 survivors honored with the Congressional Gold Medal, who were once unequal, today they were beyond equal.