Encouraged by how surprisingly readable the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform debt reduction plan is, AEHQ decided to serve up a second helping of penny-pinching proposals.

Read our last installment for background on the commission and the draft debt and deficit reduction proposal.

Maintain Radio Silence

National Public Radio came under fire for its decision to part ways with Fox News Contributor Juan Williams in October. Many critics, including some in Congress, called for a review of funding to the nonprofit news organization, which receives nearly a quarter of its operating budget from taxpayers. The Debt Commission appears willing to grand those critics’ wish.

Eliminating public funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which also funds PBS and its member stations, would save half a billion dollars annually.

President Obama has also suggested terminating two related—and redundant—programs that have fulfilled their purpose yet still receive federal funds. The Public Telecom Facilities Grant Program and the USDA’s Public Broadcasting Grants program collectively received more than $25 million in recent years, most of which was targeted to transition broadcasts from analog to digital transmission, which was completed in June 2009.

Have a Yard Sale...Literally

The federal government owns a lot of land. The United States government is the largest property owner in the country, with 1.2 million buildings, structures, and plots of land totaling 650 million acres. The Debt Commission says 64 thousand of those buildings and structures are either excessive, underutilized, or vacant, and should be sold to the highest bidder.

Selling the surplus of land is not a new idea. President Obama signed a memorandum this year directing agencies to eliminate excess properties, saving taxpayers $8 billion by fiscal year 2012. The commission’s recommendation would add another billion dollars to that savings.

To keep from repeating the same mistake twice, the commission also recommends reducing land acquisition under the Land and Water Conservation Fund. The fund exists to acquire and maintain land for federal and state management agencies, but there seems to be more acquiring than maintenance.

The president’s fiscal 2011 budget calls for a 135 percent increase in allocations for the fund, up from $263 million last year to $619 million this year. But the land the government currently owns is grossly undermanaged—the Department of the Interior suggests between $13.2 and $19.4 billion dollars need to be put into existing property.

In a discouraging display of logic, the budgets for acquisition and maintenance are entirely separate, so funds allocated for the former can’t be used for the latter. The Debt Commission’s proposal freezes purchase of new lands until the backlog in management drops to less than a billion dollars, to net $300 million in savings.

Think Locally, Act Locally

The United States has long been the leader in delivering foreign aid and assistance to allies and developing nations worldwide. The Debt Commission thinks we can afford to be a bit less generous.

“Since 2008, the budget for international development and humanitarian assistance has increase [sic] over 80 percent from over $17 billion to over $32 billion, and is expected to grow another 40 percent to over $45 billion by 2015—more than double previous levels,” the commission proposal reads.

Reducing the proposed budget for humanitarian aid and international development by 10 percent saves $4.5 billion and still allows for a 30 percent increase in aid by 2015.

Additionally, the United States pays more than $3.5 billion in “voluntary” funds to the United Nations each year. The Debt Commission suggests trimming that good will expenditure by 10 percent, saving $300 million a year.

Cutting global contributions is not the only international savings plan the commission recommends. The State Department spends roughly $10 billion a year on Diplomatic and Consular Programs, funding security, embassy upkeep, and foreign worker salaries—important expenditures all.

But the U.S. has embassies and consulates in countries that are strategically obsolete, like those in the former Soviet Bloc, that can be closed with minimal impact on the American diplomatic mission.

And, following a common theme in these proposals, the commission recommends slowing the progress of new construction. A consulate planned to be built in Krakow, Poland will cost $80 billion and house only 10 American workers.

Judge, Jury, and Inspector

One of the more quizzical suggestions on the Debt Commission’s list is requiring food processing facilities to finance inspection and food safety services, for a net savings of $900 million per year. That’s a sizeable chunk of change, but asking companies to fund their own inspections may be asking for trouble.

The Minerals Management Service was dissolved after investigations into the Deepwater Horizon oil spill revealed an almost incestuous relationship between government inspectors and the oil companies they were tasked to inspect. Years of this revolving door problem—where regulators frequently switched careers from government to industry and back—blurred the line between inspector and inspected and helped create the environment that led to the BP spill.

The Debt Commission recommends “making the[health inspection] service paid for by those who use it.” This logic applies to toll roads or cable TV, where the person who uses the service is the person who pays for it. But the end user in the case of food processing is not the processing company, but the consumer.

Leaving companies responsible for funding their own inspections—and thus controlling the paychecks of their inspectors—may lead to the same sort of cozy relationship the MMS and oil companies had before the largest oil spill in American history.

If a Tree Falls In The Forest…

Ever heard of the Rural Utilities Service? Neither have we. But we do know it costs taxpayers half a billion dollars a year to provide loans and grants to eligible small communities for what the Debt Commission describes as “programs which are outdated, overlapping, and which provide limited or questionable public policy benefits.”

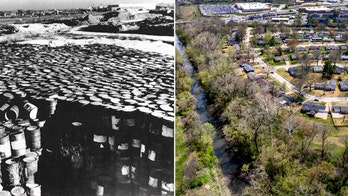

These small-impact, small-focus programs are popular items on the commission’s chopping block. The Appalachian Regional Commission exists to promote economic growth in 13 states that have counties along the mountain range. The Denali Commission serves the same purpose for residents of the remote Alaskan area of Denali, and the Delta Regional Authority does the same for eight states along the Mississippi River.

The Debt Commission wants to cut these three programs, for a net savings of just over $100 million annually, on the grounds that their effectiveness is tough to prove. “[T]he three agencies’ programs are intended, among other things, to create jobs, improve rural education and health care, develop utilities and other infrastructure, and provide job training,” the report reads. “However, it is difficult to assess whether such outcomes can be attributed to those programs rather than to the work of other governmental and nongovernmental organizations or to market forces and the effects of general economic conditions.”

Ironically, that’s the same argument opponents of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act made to challenge White House figures on job retention and creation as a result of the stimulus bill.