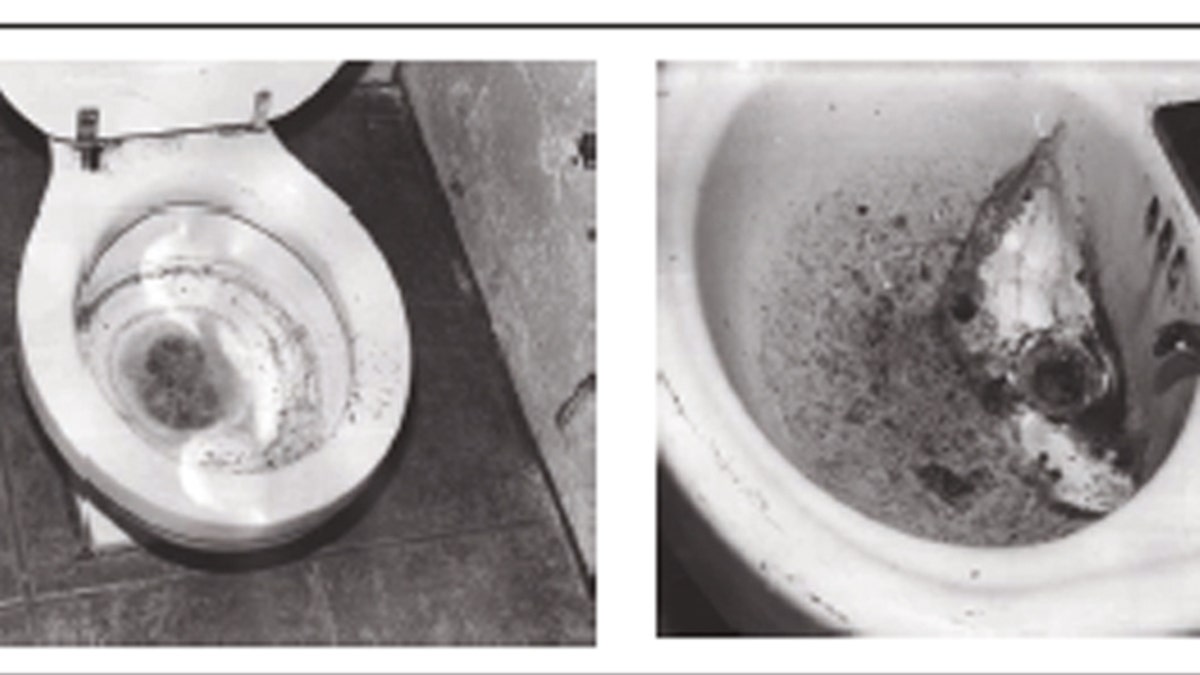

Shown here are pictures of the bathroom used by an elder abuse victim in Missouri. (GAO.gov)

Abuse of elderly Americans by their court-appointed guardians is growing into a multibillion-dollar business, and a new oversight report suggests the government is not doing enough to prevent the crimes.

A Government Accountability Office study, the results of which were released last week, examined hundreds of cases of alleged abuse across dozens of states and found several instances where guardians with questionable backgrounds sailed through the screening process. In other cases, the courts did not monitor guardians after they were appointed, "allowing the abuse of vulnerable seniors and their assets to continue."

The report sheds light on the often-overlooked problem of elderly exploitation. According to the National Council on Aging, the yearly financial loss by victims of these crimes is thought to be at least $2.6 billion. The abuse is usually committed by a family member, often a child or spouse.

With influence over their assets, these representatives are in a position to drain their savings, compel a change in the will or simply neglect the individuals they are charged with caring for.

Asked to look into the scope of the problem, the GAO examined 20 specific cases in which guardians swiped a total of $5.4 million from 158 mostly-senior victims. They were overseen by courts in 15 states, as well as in the District of Columbia, but the oversight often fell short of detecting problems with the alleged abusers.

In one case, a convicted armed robber in Missouri was allowed to become the guardian for an 87-year-old man with Alzheimer's disease. He was convicted for embezzling more than $640,000 from him, allegedly using the money to pay for a Hummer, exotic dancers and other expenses and purchases. The victim was found in a dirty basement wearing a diaper.

In another case, a social worker in Kansas who became a guardian filed no mandatory accounting documents with the court, according to the GAO. He also did not file with the Social Security Administration. The guardian and his wife were convicted for involuntary servitude and fraud, accused of sexually and physically abusing 18 victims, two of them seniors.

While doing so, the guardian allegedly paid himself more than $102,000 from the inheritance of one of the victims. He claimed the funds covered "therapy."

The GAO found "common themes" across these 20 cases. In six of them, the courts did not properly screen the guardian candidates. In 12 of them, the courts did not oversee them after they were appointed. In 11 of them, federal agencies and courts did not "communicate effectively or at all" about abusive guardians.

The GAO stressed that it is still unclear how widespread the problem of elder abuse is. But the office found more shortcomings when it tried to apply for guardianship certification in four states using a fake identity.

One fictional applicant had bad credit; another was using the Social Security number of a dead person. In all four states -- Illinois, Nevada, New York and North Carolina -- the GAO got the certification or met the requirements.

"Our undercover tests call into question the ability of these state certification programs to effectively prevent criminals and individuals with bad credit from gaining control over the lives and assets of vulnerable seniors," the GAO said in its report.