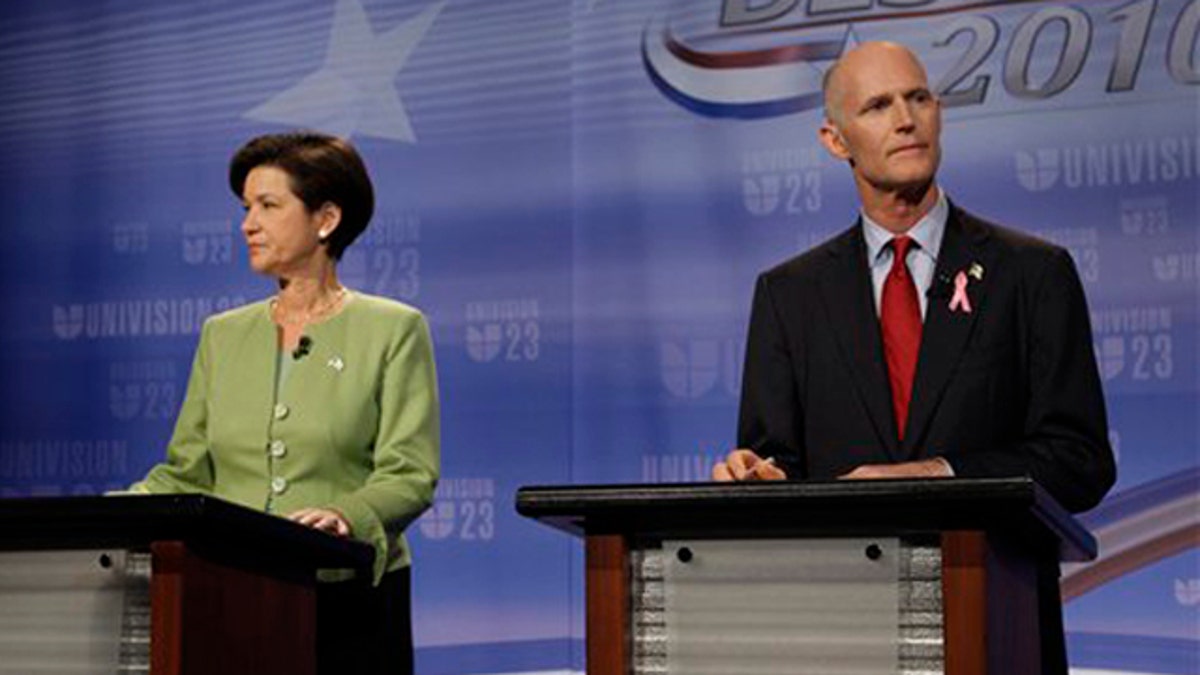

Candidates for Florida governor Alex Sink, left, and Rick Scott meet for their first face-to-face debate at Univision's studios in Miami Oct. 8. (AP Photo)

Florida's candidates for governor may have forgotten the golden rule in their quest to woo voters in their golden years.

The contest between Republican Rick Scott and Democrat Alex Sink has turned increasingly negative as the candidates vie for the support of seniors and other key voting blocs in the final stretch. Each is trying to raise alarms about the other's treatment of the retired class, with accusations of dishonesty flying in one of the country's closest races.

Scott and Sink have traded the lead in the polls ever since Scott pulled out an upset win in the August GOP primary. Despite Scott's dangerously low approval ratings, Sink has been unable to shake him as the two engage in a war of ads questioning each other's integrity.

Both candidates are touting their private-sector experience and talk in similar terms about the need to create jobs. But in a bid to gain the edge, the campaigns are turning to a seniors appeal; in keeping with the spirit of the race, they're doing so via attack ads.

Sink on Monday unveiled a two-minute, documentary-style ad called "Fraud Files" that will hammer Scott for his leadership at a company fined for Medicare fraud. The record $1.7 billion fine imposed on Scott's Columbia/HCA hospital firm has been a stand-by talking point for any number of Scott's critics and political opponents -- but Sink is going after the case with vigor as she casts the fraud as a slap in the face to Florida's seniors.

"I can't think of anything more frightening," she said at a debate Friday. "He led a company with the most massive Medicare fraud, cheating seniors and taxpayers."

Sink aired a separate ad that accused Scott's company of "ripping off seniors and taxpayers."

But Scott, who was no longer CEO when the fine was imposed against Columbia/HCA, has countered by accusing Sink of mismanaging Florida's pension fund as the state's chief financial officer.

Scott's allegations were fueled by a St. Petersburg Times report last month that said the state's financial officials defied warnings and made risky investments that led to the state's retirement account losing hundreds of millions of dollars. The article cited an audit that said Sink and other officials did not exert enough oversight.

"And now she wants a promotion?" says Scott's latest ad, which rehashed the claims.

Scott cited the pension fund at the Friday debate, and also accused Sink of overseeing a bank that gave employees kickbacks for shifting elderly customers "from safe deposits ... to risky investments." He even employed his mother, Esther Scott, to cut an ad for him. Rick Scott, she assured voters, is "a good boy."

Seniors are one of the keys to Tallahassee for statewide candidates. They not only make up a huge chunk of Florida's population, but they are disproportionately active in state elections. According to state data, about 31 percent of registered voters are 60 and up; the senior percentage voting in the 2006 general election was 43 percent.

The negative tone is unlikely to change before Nov. 2. Sink has repeatedly accused Scott of lying about her record while mocking him for pleading the fifth 75 times during the hospital fraud investigation, while Scott churns out ad after ad against Sink.

The polls suggest the ads are taking their toll on both candidates.

A Mason-Dixon poll released last week showed Sink leading 44-40 percent, but with her unfavorable ratings rising. According to the poll, 33 percent of those surveyed had a negative view of Sink, compared to 23 percent in a previous poll. Scott, meanwhile, is consistently disliked by a majority of people surveyed in Florida polls.

Still, Scott has held the lead in several other state surveys. A Quinnipiac University poll released Tuesday showed Scott leading 45-44 percent, though that represented a slight gain for Sink compared to past Quinnipiac polling.

Rasmussen pegged Scott at 50 percent in a poll released Monday, with Sink trailing at 47 percent. The poll of 750 likely voters was taken Oct. 7. It had a margin of error of 4 percentage points.