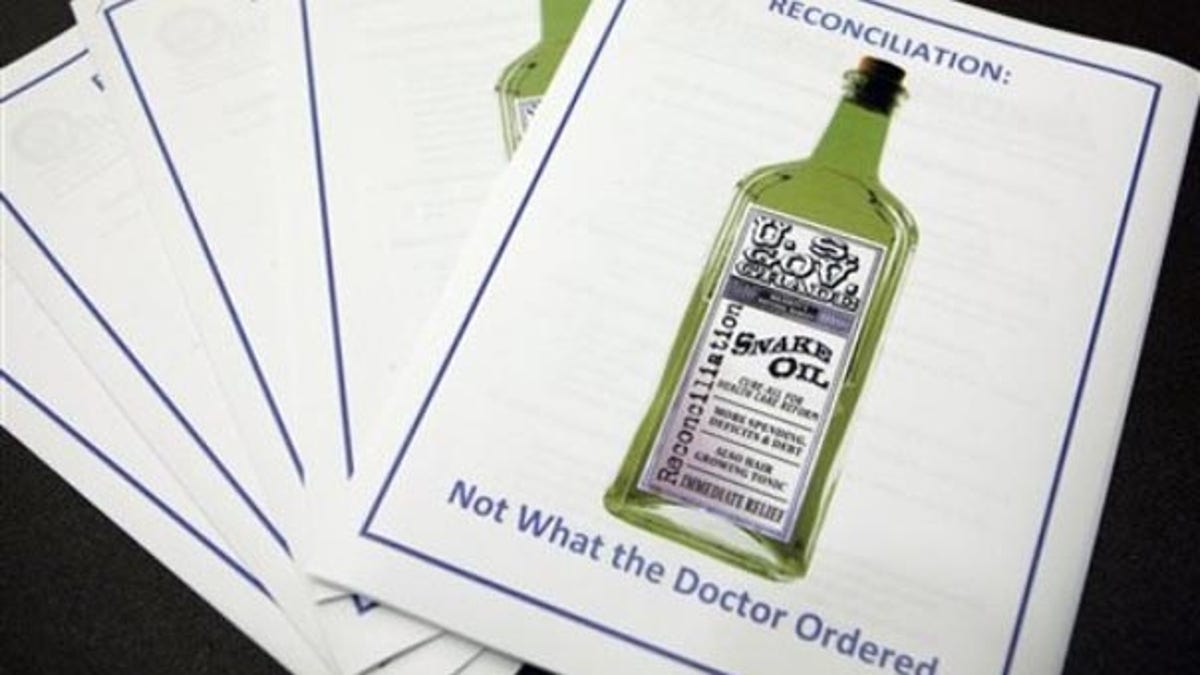

These are information packets as seen on Capitol Hill, Tuesday, Sept. 29, 2009, made available during a Congressional Health Care Caucus discussion on health care reform and budget reconciliation. (AP).

It may sound like an upbeat outcome to a messy quarrel, but "reconciliation" is hardly a smooth political solution on Capitol Hill.

Reconciliation is a seldom-used and controversial tactic that allows bills to be passed in the Senate with only a simple majority of votes, and Democrats said this week they are considering it as part of a plan to push through their stalled health care reform legislation in the face of entrenched Republican opposition.

"I think a decision has just been made -- we're just going to go ahead" with a reconciliation bill, Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, told reporters on Friday.

So what is reconciliation and why has it been described as political dynamite?

Under reconciliation,, 51 senators can amend a bill, bypassing the need for a 60-vote majority to hold off Republican delaying tactics, in particular a filibuster. Debate is limited to a maximum of 20 hours.

But legislation passed by reconciliation can only affect budget revenue, government spending and taxes.

And given that it has the potential to diffuse one of the few weapons in the minority party's arsenal, it generally has been seen as a tactic of last resort.

House Minority Leader John Boehner, R-Ohio, and House Minority Whip Eric Cantor, R-Va., wrote to White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel this week urging the administration to take reconciliation off the table as an "important show of good faith to Republicans and the American people."

"The existence of any kind of backroom health care deal among the White House and Democratic leaders would certainly make a mockery of the president's stated desire to have a 'bipartisan' and 'transparent' dialogue on this issue," Boehner, Cantor, and Pence wrote. "To ensure we can move forward in good faith, we ask that you publicly disavow these reports and assure the American people that Democratic leadership is not putting together any kind of backroom health care deal or plotting any kind of legislative trickery to pass it."

The tactic was created in 1974 to fast-track deficit-reduction efforts but has been used by both parties for a host of domestic initiatives, including COBRA, welfare reform, student aid reform, expanded Medicaid eligibility and increases in the earned income tax credit.

While Republicans are fiercely opposed to reconciliation, they used the tactic to push through former President Bush's massive tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 and to approve oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Democrats increasingly have looked to reconciliation as viable option since Republican Scott Brown won a special election last month in Massachusetts to become the state's new U.S. senator, depriving Democrats of their 60-vote supermajority and sidelining the health care reform bills passed both the House and Senate late last year.

If Democrats decide to use reconciliation for health care, House Democrats first would have to hold their nose and approve a Senate bill that was passed Christmas Eve, sending it along on for President Obama to sign. Then the Senate would use reconciliation to make the changes that address some of the major substantive concerns that have been raised.

Senate Democratic leaders prefer not to go the reconciliation route. Moderate Democrats are resistant, and Republicans are urged Democrats to abandon the idea.

But some Democrats believe the threat of reconciliation will be an effective negotiating tool going into the bipartisan health care reform summit scheduled for later this month.