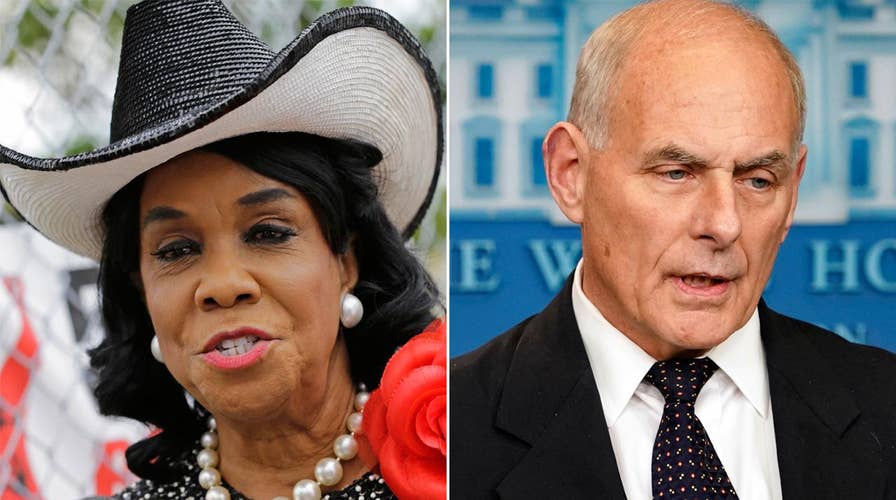

Wilson refuses to back down after Kelly's defense of Trump

White House chief of staff defends the president's call to a Gold Star widow.

On Thursday, John W. Kelly, the White House Chief of Staff and a retired four-star Marine general, rightly told the world that America’s troops deserved their countrymen’s respect, falsely and wrongly trashed Congresswoman Frederica Wilson, and arrogantly refused to take questions from reporters who lacked a nexus to a fallen American soldier or a Gold Star family. A day later, White House spokeswoman Sarah Huckabee Sanders proclaimed that ex-generals should be immune from criticism, or as she put it, “If you want to get into a debate with a four-star Marine general, I think that’s something highly inappropriate.”

Sorry, but kiss the ring, bend the knee, hail Caesar’s Praetorian is not the American Way. We, the People, pay these pols’ salaries, and they owe us the very same respect that they themselves expect. They also owe us answers. Indeed, when Chuck Schumer, the Senate Minority Leader, is unaware of there being 1,000 U.S. troops in Niger we deserve the truth, like yesterday.

Past-held rank and nexus to power should not be shields from inquiry. As Gen. H.R. McMaster, the current National Security Adviser and Kelly’s colleague wrote in his book “Dereliction of Duty:” “Failure in Vietnam was the result of a uniquely human failure, a responsibility shared by LBJ, his principal military and civilian advisors. The failures were many and reinforcing: arrogance, weakness, lying in the pursuit of self-interest and above all, the abdication of responsibility to the American people.” In the words of General David Petraeus, generals are “fair game.” It doesn’t get any simpler than that.

Against this backdrop, it is time for us to take a hard look at compulsory national service. Indeed, if the political cacophony surrounding the condolences extended to the family of Sgt. La David Johnson did anything, it was to lay bare the gap between the other one-percent, those Americans who actively serve in our armed forces, and the rest of us. As one lieutenant colonel stationed in Iraq said over a decade ago “we’re at war, America’s at the mall.”

As the tectonic shifts of diversity bring their own political challenges, national service could yield a badly needed common experience. It would also remind us that we all are part of America at a time when political rancor is the rule.

Sadly, with the exceptions of Vermont and Maine, military service has morphed into the province of Red State America, while the chasm in the ethos and demographics of our nation’s service academies on the one hand, and our elite universities on the other, grows ever larger. As retired General Dennis Laich and Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson recently observed, military “deployment burden” crystalizes the “urban/suburban vs. rural divide.”

Let’s be real. Scarsdale isn’t sending their best and brightest to West Point, while there aren’t too many kids from Havre, Montana, roaming the Ivy League. To quote Abraham Lincoln and Jesus, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

Practically speaking, national service would mean that once again Americans from all walks of life would get to know each other, North, South, the Coasts, the Great Plains, and the Mississippi Delta. As the tectonic shifts of diversity bring their own political challenges, national service could yield a badly needed common experience. It would also remind us that we all are part of America at a time when political rancor is the rule, and the word “secession” gets bandied about as a threat or an applause line.

National service could also bring the role of the military into proper perspective, as deserving something greater than a shoulder-shrug, but also less than awe. The abstract morphing into reality has a way of doing that.

Universal national service would mean that more Americans would have skin in the game the next time politicians suggest another “excellent” overseas adventure. Fewer op-ed writers and congressmen urging that others make the supreme sacrifice while they sit safely out of harm’s way would be a welcome change.

General Kelly was right in one very important sense, too few privileged Americans bear the burdens of war. Yet the way to address that problem is to engage the rest of us, not to censor or lash out from the White House on live television.