Religious liberty case brings first big test for Gorsuch

Judge Andrew Napolitano provides insight into the Supreme Court

Where does establishing end, and prohibiting begin?

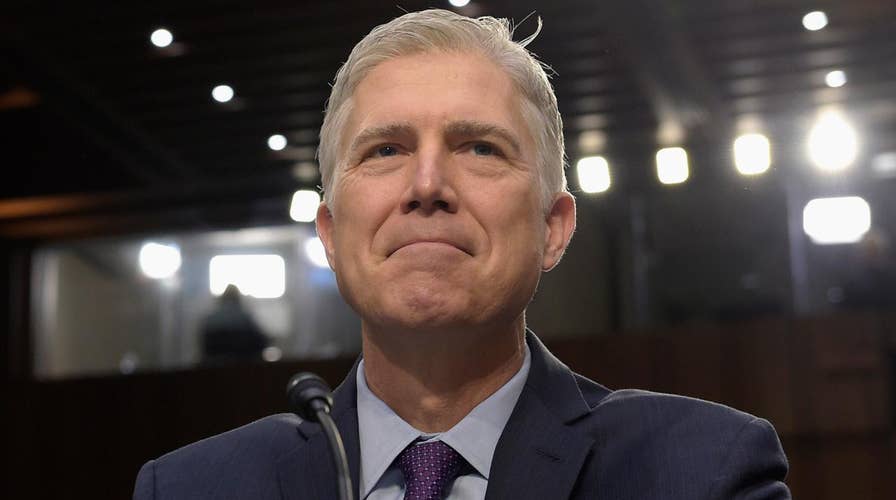

That, essentially, is the question the U.S. Supreme Court will answer in the case of Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer, which the high court will hear on April 19. It is likely the most important religious freedom case before the court this term, made even more significant by it being one of the first oral arguments in which newly minted Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch will participate.

The First Amendment charges Congress—and, by incorporation, the states—to “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” But what to do when, in the normal course of their activities in the public square, citizens of one religious faith are shunned from participating in a public benefit offered to everyone?

This is not a case about the too-often erroneous interpretation that the First Amendment’s establishment clause trumps its free exercise clause—that government must always err on the side of treating religious groups like asbestos in the ceiling tiles of society. The two are not in conflict: “Not establishing” doesn’t mean “actively opposing” or that government must deny religious groups even secular public benefits available to everyone in order to not “establish” religion..

That is government hostility toward religion disguised as a way to avoid favoritism. The Trinity case brings to the forefront a different interpretation: government hostility disguised as neutrality.

The crux of Trinity is the idea that in situations involving public programs and services—from fire and police to garbage pick-up—religious groups should be treated equally and not discriminated against solely because of their religious status.

Trinity Lutheran Church in Columbia, Missouri, owns and operates a preschool, The Learning Center. Like most schools, The Learning Center grapples with the challenge of providing a reasonably safe setting for its youngsters’ outdoor play and activities. Knees, elbows, bones, and skulls are especially vulnerable, during children’s formative years, to the hard realities of solid ground, and the pure joys of swings, teeter-totters, slides, and monkey bars can only postpone those realities so long.

In recent years, schools, parks, and children’s hospitals nationwide have begun covering their playgrounds with rubberized material made from old tires. Soft and durable, the material cushions the harder landings of recess activity while providing states with an environmentally friendly alternative to storing, stacking, or burning the tens of thousands of tires that pile up annually at city dumps nationwide.

Missouri came up with a grant program that makes this expensive rubberized ground cover more accessible to financially pressed groups and facilities. By meeting basic requirements with regard to safety, usage, community service, etc., these groups can put themselves in contention to be reimbursed for the monies they invest in rubber ground cover.

The fine print of the application for Missouri’s program says that religious groups need not apply. Trinity Lutheran officials’ efforts to clarify that discrimination met with evasive responses from the program’s administrators, so the church applied anyway—and scored high enough in the requisite factors to place fifth out of 44 applicants. State officials were all set to award a grant when they belatedly realized the school’s church affiliation and denied the award, citing state constitutional prohibitions against government “aid” to religious groups.

The obvious solution to this perceived quandary is neutrality. Real neutrality. The government shouldn’t give a school a grant it hasn’t earned simply because it’s church-owned—but neither should it withhold that same grant when the school has earned it, simply because the school is owned by a church.

Otherwise, the government is forced to argue that the safety of children in a church preschool is somehow less important than the safety of children in other preschools. And where exactly does that logic lead, in terms of other government protections?

Under the state’s principle, it would be allowed to refuse to send the fire department if a religious pre-school was on fire, or to withhold the police in an emergency at a church. The state’s primary job should be to promote the health, safety, and welfare of all of its citizens, regardless of their beliefs.

So, the Learning Center staff can’t quite fathom where the problem lies. In addition to the above, everyone who purchases tires in Missouri, including the people who run the preschool and the families that use their playground, pay into the fund for the tire grants. But now the state is saying that they can’t benefit from what they have paid in if the grant is going to a faith-based preschool—one widely regarded as one of the premier schools in the Columbia area. The school is so well respected that, of the 82 children enrolled last summer, only four came from church families.

And don’t forget that we are talking about a playground that the church makes available outside of school hours to anyone in the neighborhood, so that any family can come make sand castles or push their children on a swing.

Given that easy mutual tolerance, what threat is the state trying to block with its policy? Surely a government that strives to be color blind when serving the public should endeavor to be religion blind as well. Instead, Missouri officials contend that their constitution actually requires them to be hostile to people of faith and religious organizations—and so they’re effectively punishing this church for meeting all the other standards of their program. That’s nothing more than religious discrimination, cloaked in the Establishment Clause.

They’re calling this “the playground case,” but make no mistake. The Trinity case cuts to the ABCs of religious freedom—and the most critical implications of the First Amendment.