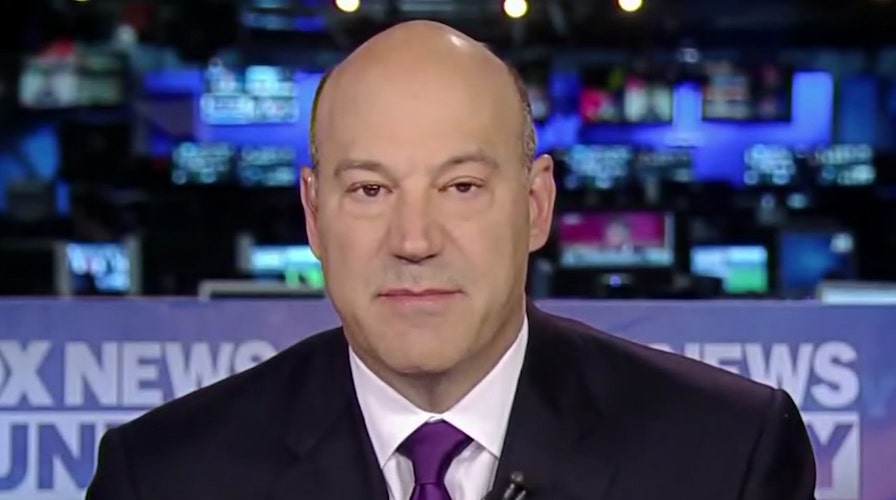

Gary Cohn: Access to health care is main priority

White House national economic adviser talks Trump agenda

Conservatives wonder: what the heck is Gary Cohn doing in the Trump White House? Cohn, a life-long Democrat and latecomer to the Trump train, is White House Economic Council Director. The former president of Goldman Sachs is reportedly ascendant, while Steve Bannon, Peter Navarro and Stephen Miller see their stars fading. This is not good news for Trump supporters, or for the GOP.

Donald Trump was elected by angry Americans: people furious at Obama’s progressive agenda, incensed that China was stealing our jobs and disgusted by milquetoast Republicans who had not delivered on campaign promises to ditch Obamacare, curb illegal immigration and spur faster economic growth. Trump voters were fed up with Obama’s global ambitions and celebrated his America First message.

His backers didn’t care that Trump knew little about policy or Washington; he was in a sense an empty vessel when it came to translating common sense ideas into legislation and regulations. Now, though, they see that vessel being filled in part by individuals who do not share their views. One of those is Gary Cohn, who has emerged as a powerful but discordant voice.

Democrats and the mainstream media have rejoiced as they have watched Cohn, along with Jared Kuschner, his wife Ivanka Trump and former Goldman Sachs partner Dina Powell, soften White House policy on issues such as cutting regulations, immigration enforcement and Obamacare repeal.

When Gary Cohn recently lofted the possibility of bringing back Glass-Steagall, the Depression-era law that allowed big banks to engage in investment banking, Senator Elizabeth Warren was reportedly giddy with joy. The law, which was repealed by Bill Clinton in 1999, is viewed by progressives as having helped cause the financial crisis. Leaving a meeting in which Cohn mused about reinstating the bill, Warren reportedly said to an aide, “Has the whole world gone mad? Am I on the same page as a former Goldman executive? My entire worldview has been shattered.”

Her confusion is understandable. Not that long ago, Cohn joined Trump in ardently pressing to dismantle the cumbersome bank regulations contained in Dodd-Frank. So upset was Warren over Cohn’s determination to knock down those rules, which are loathed by Wall Street, that she and fellow senator Tammy Baldwin wrote a letter to Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein demanding proof that he and his former colleague were not in cahoots.

It is worth noting that while reinstituting Glass-Steagall would be problematic for all the leading financial institutions, it would hurt Goldman much less that the big banks who are its major competitors.

Cohn’s former political affiliation and past support of President Obama is not important. What is important is how his liberal views could distort President Trump’s agenda. For example, Cohn has taken a major role in crafting the White House’s stance on tax reform. Recently, in searching for a revenue source needed to balance proposed cuts in tax rates, it was reported that Cohn suggested a carbon tax. (He has since denied advocating that approach.) The idea was quickly shot down, but its very consideration was alarming. Trump campaigned on dismantling Obama’s Clean Power Plan, has proposed sharp cuts in the budget of the EPA and wants to resuscitate our coal industry. How does a carbon tax fit into that program?

Cohn is also reportedly a free-trade advocate, and has appointed Andrew Quinn to the Economic Council as Special Assistant to the President for International Trade. Quinn was one of the lead negotiators of the multi-national TPP trade pact that Trump savaged on the campaign trail and has since junked. How will Quinn work to revise our trade commitments and revise NAFTA?

For the most part, Cohn’s hires for the National Economic Council have been right-leaning and likely to support President Trump’s campaign pledges. Kenneth Juster, for instance, tapped to be head of international affairs, served under both G.W. Bush and his father, and is a strong advocate for boosting exports.

It is also true that there are other sound voices on economic policy within the administration. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross is nobody’s fool, and will support an aggressive U.S. trade posture. Though conservatives have reservations about Steve Mnuchin, they applaud some of his picks, like economist David Malpass for international affairs and Drew Maloney for legislative. Mnuchin’s choice of major Hillary fundraiser Craig Phillips to oversee financial regulation, is less popular.

Still, access to the president, enjoyed by Cohn and others on the White House staff, is critical. Cohn is known as a big, forceful straight talker. He is also successful – the kind of individual that Trump instinctively trusts. One of his former Goldman colleagues describes him as a “tough operator,” who would be comfortable and probably victorious engaging in the kinds of turf battles rumored to be underway in the White House.

It is early days, but ongoing power struggles could well determine the success of the Trump presidency. He needs to remember who put him in office, and who he will rely on to keep him there. It wasn’t Manhattan elites or Democrats, it was people who are counting on him to cut taxes, bring back jobs, dismantle our stifling red tape, and rein in illegal immigration. A recent Quinnipiac poll showed Trump losing ground with exactly the people who elected him – Republicans, white voters and men. And guess what, he isn’t making up for those losses with newly affectionate Democrats.