Democrats vow to threaten filibuster Gorsuch confirmation

Chief congressional correspondent Mike Emanuel reports from Capitol Hill

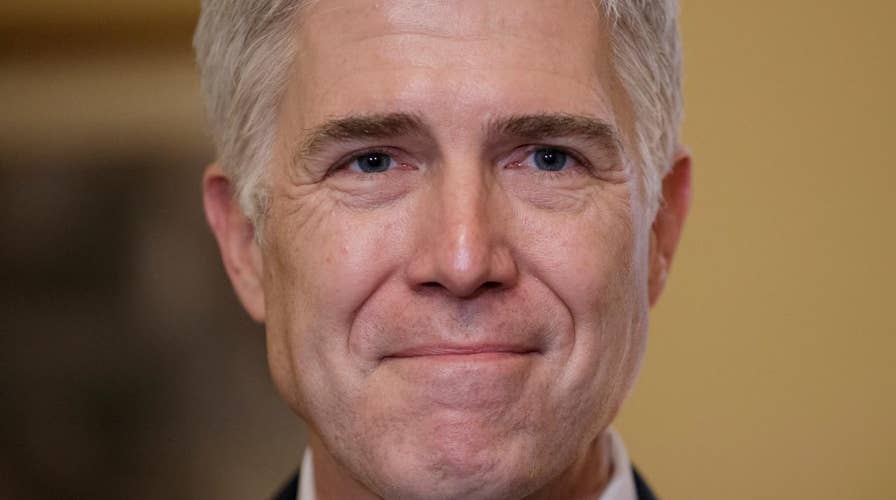

Tuesday night, President Trump nominated Judge Neil Gorsuch to fill the Supreme Court seat left vacant by the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s untimely passing. As the intellectual architect of the effort to restore the judiciary to its proper role under the Constitution, Justice Scalia was a singularly influential jurist. To say that he leaves big shoes to fill is an understatement. Any worthy successor to Justice Scalia’s legacy must not only be committed to continuing his life’s work, but also capable of delivering the sort of intellectual leadership that Justice Scalia provided for decades.

Of all of the potential candidates for this vacancy, Neil Gorsuch stands out as the one best positioned to fill this role. His résumé can only be described as stellar: Columbia University, Oxford, Harvard Law School, clerkships on the D.C. Circuit and Supreme Court, a distinguished career in private practice and in the Department of Justice, and more than a decade of service on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit.

Even among his many talented colleagues on the federal bench, Judge Gorsuch’s opinions consistently stand out for their clarity, thoughtfulness, and reasoning. In the words a colleague appointed by President Carter, Judge Gorsuch “writes opinions in a unique style that has more verve and vitality than any other judge I study on a regular basis.” That colleague continues: “Judge Gorsuch listens well and decides justly. His dissents are instructive rather than vitriolic. In sum, I think he is an excellent judicial craftsman.”

There can be no doubt that Judge Gorsuch has the credentials to be an effective member of the Supreme Court. Nevertheless, I have long held that no nominee’s résumé alone—no matter how sterling—should be considered sufficient to merit confirmation to the Supreme Court. Rather, we must also consider a nominee’s judicial philosophy.

On this count, Judge Gorsuch’s opinions and writings reflect an understanding of the proper role of a judge under the Constitution. For example, in a lecture he delivered last year shortly after Justice Scalia’s passing, Judge Gorsuch affirmed his allegiance to the view that judges should “strive . . . to apply the law as it is, . . . not to decide cases based on their own moral convictions or the policy consequences they believe might serve society best.”

In that same lecture, Judge Gorsuch also quoted Justice Scalia’s statement that a good judge will often reach outcomes he does not personally agree with as a matter of policy. Such a notion should be uncontroversial. Indeed, many of Justice Scalia’s greatest opinions came in cases in which I suspect he would have voted differently as a legislator.

Unfortunately, the idea that judges should decide cases based on law, not policy, might seem foreign to a casual observer of Supreme Court media coverage, in which cases are invariably discussed in terms of their politics. Decisions and justices are regularly described as liberal or conservative, with little attention paid to rationale and methodology, the matters properly at the core of a judge’s work.

This phenomenon reflects a regrettable dynamic Justice Scalia himself lamented. As the late Justice observed, when judges substitute their own policy preferences for the fixed and discernible meaning of the law, the selection of judges—and in particular, the selection of Supreme Court justices—becomes a “mini-plebiscite” on the meaning of the Constitution. Put another way, if judges are empowered to rewrite the law as they please, the judicial appointment process becomes a matter of selecting life-tenured legislators largely immune from accountability.

If we buy into such a system, a system deeply at odds with the the Founders’ view of the judiciary, then we can easily see why judicial selection becomes a matter of litmus tests on hot-button policy issues.

This is a fundamentally misguided way to approach judicial selection. Such an approach undermines the Constitution and all of the crucial principles it enshrines, from the rule of law to the notion that government’s legitimacy depends on the consent of the governed.

A good judge is not one we can depend on to produce particular policy outcomes. Rather, a good judge is one we can depend on to produce the outcomes the law and the Constitution prescribe. Neil Gorsuch is exactly that sort of judge, and deserves a smooth and speedy confirmation.