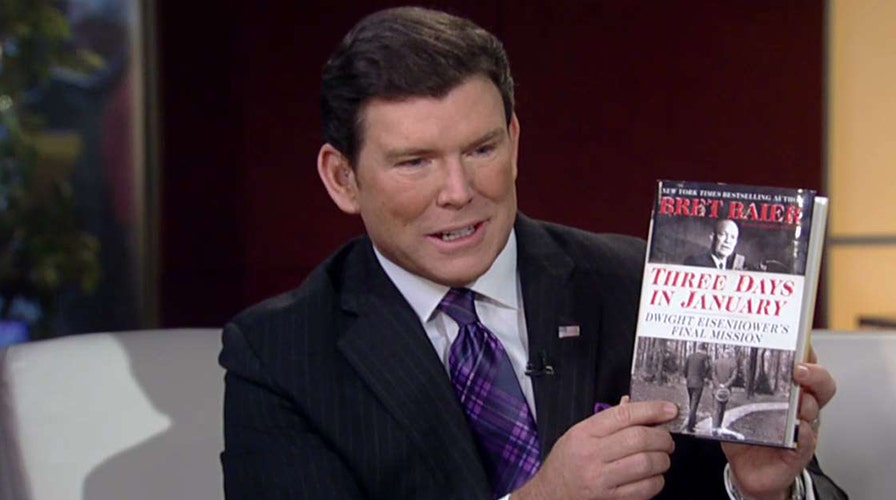

Bret Baier opens up about 'Three Days in January'

The 'Special Report' host talks about his new book on Eisenhower

Tuesday night President Obama delivered his farewell to the nation, choosing the McCormick Place in his Chicago hometown as the stage.

The dramatic setting, the enormous crowd and the almost concert-like optics set this apart from every other presidential farewell. With echoes of past speeches and playing off the themes of the hope and change campaign of 2008, the speech was part emotional goodbye and part pep talk for his party -- after Democrats were decisively defeated in an election Obama repeatedly said was meant to secure his legacy.

In his address, President Obama defended that legacy, but he also sought to reach beyond parties and disappointments to give the American people his idea about a way forward.

The speech had special interest for me beyond the current political scene. I was listening particularly closely because my new book on Dwight Eisenhower, "Three Days in January: Dwight Eisenhower’s Final Mission," is built around his iconic farewell address, delivered on January 17, 1961. Serendipitously, the book launched on the day of President Obama’s farewell speech.

It was that research on Eisenhower—and particularly the final days of his transition leading up to John F. Kennedy’s inauguration--that first got me thinking about the meaning of the presidential farewell address. What is its purpose for presidents then and now?

Eisenhower was a great student of George Washington whose dramatic farewell in 1796 is worth our attention. That transition in 1796 was a critical moment of truth for our young nation, which had yet to experience what would become one of its most precious traditions—the peaceful transition of power.

It had literally never been done before. Washington’s farewell, printed and distributed in a newspaper article, was the decisive moment when the nation learned he would not seek a third term, but rather, would pass the baton and step aside.

With great humility, the man who had been at the helm of our government through its first years, wrote, “Interwoven as is the love of liberty with every ligament of your hearts, no recommendation of mine is necessary to fortify or confirm the attachment.”

In other words, he was communicating that the presidency was not about the man but the office, and it was the Constitution that would see the country through. Still, he went on to give a forceful defense of the principles upon which the country was founded, and a strong warning against foreign intervention and for national unity.

As evidence of the power of this enduring message, every year in February, in honor of Washington’s birthday, the U.S. Senate reads aloud the text of his farewell address—a tradition that has been observed since 1896. Clearly, he set the mold.

President Obama made a point of referencing Washington’s farewell in his own speech Tuesday, particularly his warning that self-government is the foundation of our nation and we must guard it always with “jealous anxiety.”

Arguably, Eisenhower is the only president since Washington whose farewell words have made a lasting impression. In saying goodbye, American presidents typically attempt to accomplish two things: defend their records and look ahead to the challenges facing the nation. The speeches are rarely memorable, and that is one reason Ike’s stands out.

Three presidents in our modern era never had the opportunity to give farewells. Roosevelt and Kennedy died in office. Nixon gave a hasty speech that was more of a personal goodbye as he prepared to escape the shame of his resignation. With other modern presidents, the farewells seem to reflect the men themselves. Some of them were crafted in the twilight of disappointing terms. Lyndon Johnson recited a catalog of accomplishments delivered not as a separate farewell but in his final state of the union address before congress. His lengthy speech was ponderous and tortured. Carter, still resentful about being defeated for a second term, was somber while detailing America’s ills.

Reagan’s farewell isn’t as memorable. But reading it, one is often struck by how perfectly it reflected the man with all his warmth and personal feeling. Speaking from the Oval Office, he said, “People ask how I feel about leaving. And the fact is, ‘parting is such sweet sorrow.’ The sweet part is California and the ranch and freedom. The sorrow—the goodbyes, of course, and leaving this beautiful place.” He went on to tell story after story in his masterful style. Rather than a policy checklist Reagan chose to speak of higher ideals and call for patriotic engagement.

Bill Clinton and George W. Bush both said in their speeches that they were more optimistic about America than when they began their presidencies—a striking statement for Bush in light of 9/11 and the ensuing war on terrorism.

President Obama’s farewell came at the end of an acrimonious election, addressing a nation that is deeply divided. In the soaring oratory that is his trademark, he called on the nation to lace up its shoes and get to work, saying, “The long sweep of America has been defined by forward motion.” While taking veiled swipes at the incoming Trump administration whose agenda is starkly different than his, he covered little new ground, mostly repeating his standard theme of hope, and declaring as his two immediate predecessors had that he was more optimistic than ever about the future of America.

Watching this speech, it seems clearer than ever that Dwight Eisenhower’s farewell stands out as the most important of our era—and possibly the most significant address since Washington’s. Notably, the speech only received cursory attention at the time. The country and the media were swept up in the excitement about a glamorous president-to-be. Only later, after Kennedy was mired in problems, and then Johnson was burdened with the trials of Vietnam, did people begin to take a new look at Eisenhower’s words.

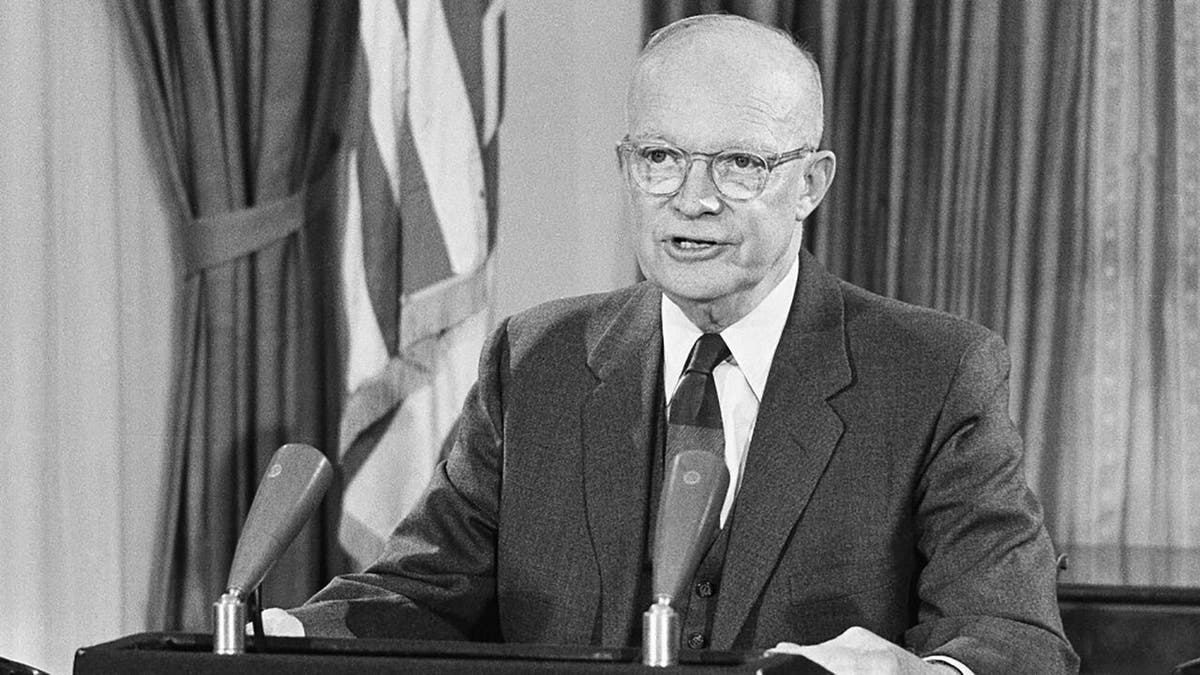

Eisenhower gave the speech not before a cheering crowd or a congressional chamber, but in a black-and-white televised address, sitting at his desk in the Oval Office. The speech was not an afterthought. In fact, it had been a year and a half in the making, a serious effort involving some thirty drafts. At the Eisenhower Library, you can hold the original drafts of the speech with gloved hands, and see Eisenhower’s many scribbled notations in his effort to get it just right. In the end, although Ike was speaking to the country, he was also addressing an audience of one—president-elect Kennedy. He was determined to pass on to this eager young man the importance of balancing the interests of the nation, a caution about the dangers of an untamed military-industrial complex, and the importance of bipartisanship.

In many ways Eisenhower’s farewell still speaks to our times. The themes are a template for the modern era. We still struggle with that delicate balancing act, while we face new questions about our place in the world.

Eisenhower’s address survives because it wasn’t about him and his accomplishments. It wasn’t soaring or poetic, just the plainspoken talk of a man giving a warning and a reminder of who we are as a nation and what we need to do to protect our sacred democracy.

As he said quite simply—and, like President Washington —“You and I, my fellow citizens, need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the nation’s great goals.”