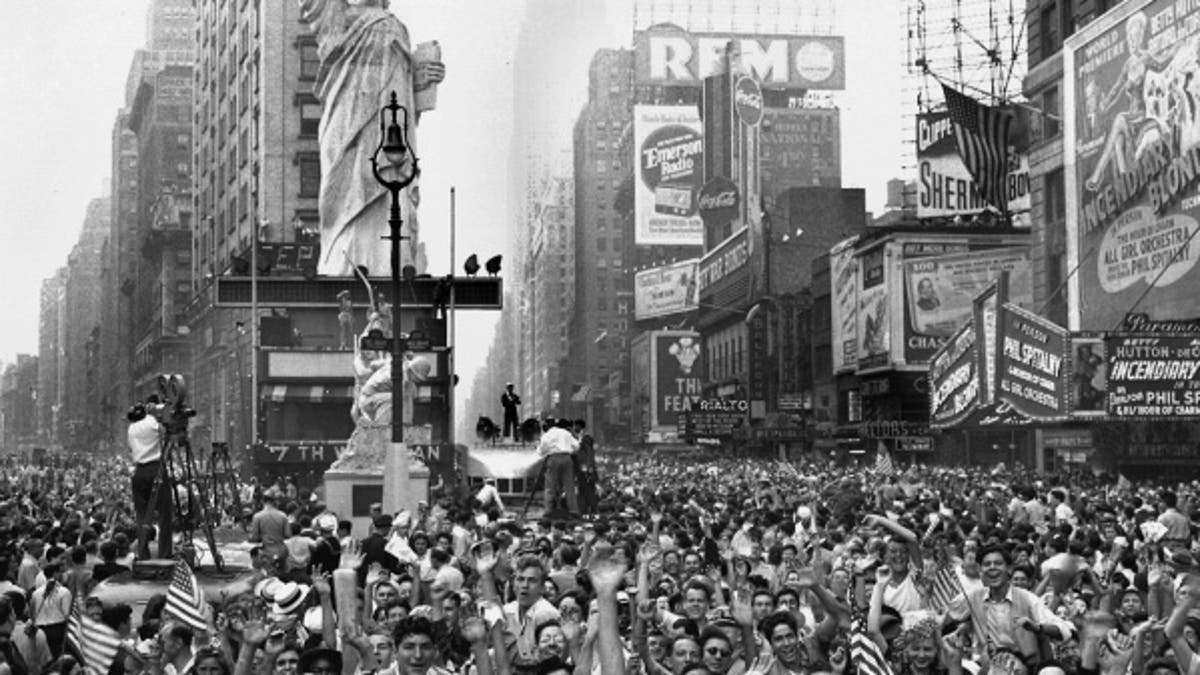

FILE -- Thousands of people celebrate VJ Day on New York's Times Square August 14, 1945 after Japanese radio reported acceptance of the Potsdam declaration. (AP Photo)

Seventy years ago, the world went wild with joy as Japan announced its intention to surrender unconditionally and end the Second World War. Among the Allies, the date would be marked as V-J Day for “Victory over Japan Day” or V-P Day for “Victory in the Pacific Day.” In the time zone of the United States, it was August 14, 1945.

When President Harry S. Truman announced the news, the streets of America erupted with spontaneous celebrations of jubilation, relief, and—for those who had lost loved ones in the conflict—a poignant melancholy. There were similar outpourings around the globe, from Sydney, Shanghai, and Manila to London, Paris, and Montreal. Perhaps there was no greater celebration than among the overflow crowd that gathered in New York’s Times Square, where Life magazine photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt snapped an iconic image of an exuberant sailor kissing a startled nurse.

The previous two weeks had been marked with uncertainty and a new horror. In late July, representatives of the United States, Great Britain, and China meeting in postwar Germany—the Soviet Union was present but technically still neutral with Japan—issued the Potsdam Declaration. It called for Japan’s immediate and unconditional surrender to avoid complete destruction.

When factions within the Japanese government delayed a response, some hoping the Soviet Union might broker better terms, Truman ordered an atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6. Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. The debate continues over the necessity and appropriateness of their use.

In the seventy years since, there has not been such a definitive end to a conflict. “None of us knew then,” war correspondent Theodore H. White later wrote in his memoirs, “that this was the last war America would cleanly, conclusively win. We thought it was the last war ever.”

The day after the Nagasaki bomb, the Japanese government agreed to the Potsdam terms on the condition that the sovereignty of the emperor was preserved. Acting for its Allies, the United States accepted this accommodation, but was emphatic that the authority of the emperor and the Japanese government would be subject to an appointed Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, who would take whatever steps necessary to effectuate the unconditional surrender terms.

There were strong indications that Japan would agree, but Truman and the U.S. Joint Chiefs kept up military pressure until such a response was certain. In the waters off Japan, aircraft carriers of Admiral William F. Halsey’s Third Fleet prepared to launch another round of air strikes on the morning of August 14, Washington time. Suddenly, Halsey received a radio flash from Pacific headquarters ordering him to suspend air operations immediately. Japan had accepted the absolute terms. All other offensive operations were to cease, although a wary watch was to be maintained.

V-J Day celebrations spilled over into the next day, although Truman noted that he would designate an official V-J Day—to match that of V-E Day in Europe—only after the articles of surrender were officially signed. He appointed General Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and charged him alone with the authority to receive Japan’s signed surrender document on behalf of the United States, Great Britain, China, and their other Allies. The Soviet Union had belatedly declared war on Japan, but MacArthur’s orders made it clear to the Soviets that their request to preside as co-equals at the formal surrender was firmly denied.

That moment of drama, and Truman’s official V-J Day proclamation, occurred on September 2 aboard the American battleship Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay.

In the seventy years since, there has not been such a definitive end to a conflict. “None of us knew then,” war correspondent Theodore H. White later wrote in his memoirs, “that this was the last war America would cleanly, conclusively win. We thought it was the last war ever.”[White, In Search of History, p. 228.]

Seventy years after the conclusion of the worldwide horror of World War II, the numbers of those who participated in the conflict on all sides diminish every day. By the time the seventy-fifth anniversaries of the war’s end are noted, very few of these veterans will be left. In that summer of 1945, they indeed thought they had fought the “last war ever.”