Shakespeare, Henry Folger and the mania of collecting things

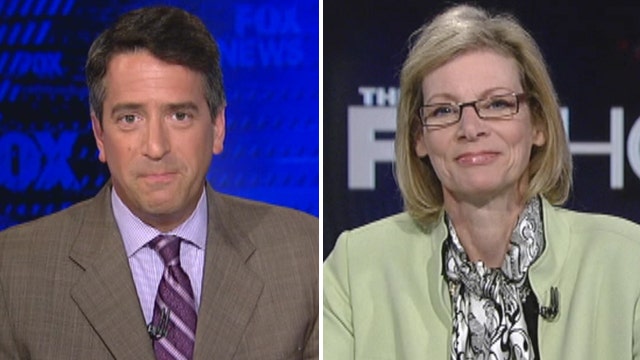

Fox News' James Rosen speaks to author Andrea Mays about 'The Millionaire and the Bard'

When William Shakespeare died, in 1616, it’s not as if he were Shakespeare or anything. After all, the Bard had been retired for a few years, with his works seldom performed and eighteen of the plays he had written – including some that would later be recognized as major works, like "Twelfth Night," "Julius Caesar," "Macbeth" and "The Tempest" – sitting around collecting dust, unpublished and unheralded. Still more of Shakespeare’s works had disappeared altogether, never to be recovered or enjoyed by anyone.

In 1623, two fellow actors from the Globe Theatre, John Heminges and Henry Condell, reckoned a tribute was in order and gathered together three dozen of their deceased friend’s plays and manuscripts. These they published in a massive collection known as the First Folio. It was the earliest testament to Shakespeare’s enduring triumph as the greatest English-language writer in history, and copies of the First Folio would, over time, become exceedingly scarce and highly valued. By the late nineteenth century, it’s believed that fewer than 200 copies of the First Folio’s original production run of 750 copies remained in existence.

Determined to get his hands on an original set was a Brooklyn-born lawyer and business executive of the Gilded Age named Henry Folger. Educated at Amherst, Folger would rise to become president and chairman of Standard Oil of New York, the pioneering business founded by John D. Rockefeller. Along the way, however, family financial difficulties required young Folger to take out loans to finish his schooling. That’s when he discovered Shakespeare, and commenced his quixotic effort to purchase every scrap of Shakespeareana he could find – a pursuit which led Folger to take out still more loans and IOUs across his spectacular business career, even when he was earning what would be the equivalent, in today’s dollars, of over a million a year.

“Henry and his wife Emily collected, over thirty years, anything you can imagine that is related to Shakespeare,” said Andrea Mays, an economics professor and the author of "The Millionaire and the Bard: Henry Folger’s Obsessive Hunt for Shakespeare’s First Folio" (Simon & Schuster, May 2015), during a recent visit to "The Foxhole." "Literally anything you can imagine." Folger borrowed against his wife, took out Standard Oil stock as collateral, moved funds around here and there as needed, all to bankroll what was quickly developing into an undeniable and irrepressible obsession.

The fruits of those labors are on display at the Folger Shakespeare Library on Capitol Hill, a world-renowned research institution central to any academic inquiry into the Bard and his works. By the time of Folger’s death, in 1930, he owned eighty-two of the 153 copies of the First Folio then known to exist. Today, with fresh discoveries still occurring as recently as last summer – when a small library in northern France turned up an original copy amongst its holdings, untouched for 200 years – at least 233 copies of the First Folio are believed to exist. The book stands as the most expensive in the world to purchase, exceeding even the cost of the Gutenberg Bible, of which fewer than fifty copies survive and a complete copy has not been sold, according to published reports, since 1978.

MAYS: 1889 is really [Folger’s] first big acquisition. He goes into an auction house called Bangs in New York and he buys not a First Folio, but a Fourth Folio, which was cheaper, and that was what he could afford. He was just out of school. He didn't have savings. He still had this loan left to pay off, so he bought this book for $107.50, and put that on layaway…And that was really the beginning of the quest….

ROSEN: What are your thoughts about collecting as a pursuit? Is it, as my wife likes to say of me, evidence of a disorder, ipso facto? Or what – how do we consider collecting?

MAYS: Well, that's a tough question because there's probably a very fine line and you, as a collector, don't know when you have crossed it. That's part of the problem….

ROSEN: But, whether you're collecting on Henry Folger's level – where crossing a line is going to be a distinctly greater possibility, because you're not obstructed by any financial hindrance, right? – or whether you're collecting at my level, or whether you're a boy collecting this year's Topps baseball cards, let's say, or Pokemon cards, like my son collects, is there, from where you sit, a mania at work, no matter who we're talking about? Because there's – it's – in essence, it's an attempt to impose order on the randomness of the universe, correct?

MAYS: It is. It's also a way of framing the rest of your life, that you see it all through the lens of this Shakespeareana.

"The Millionaire and the Bard" has been hailed as a literary detective story, tracking Henry Folger as he relentlessly stalked his prey; but it has also been described, as in a glowing review in the New York Times by Stephen Greenblatt, editor of "The Norton Shakespeare," as “an American love story,” one that chronicles a besotted man’s burning passion for an artist who predated him by three centuries.

However it is properly categorized, the book also reflects a labor love – and detective work – for Mays herself. An economics professor at California State University at Long Beach, she grew up listening to recordings of Shakespeare plays at the New York Public Library in Manhattan, and she did not flinch from arriving at a firm opinion in the enduring mystery of whether Shakespeare was – well, who he’s cracked up to be.

Asked about the theory that Shakespeare was really the contemporaneous writer Christopher Marlowe, writing under a pseudonym, and similar theories that posit that William Shakespeare did not actually write his famous plays, Mays notes that "the English were meticulous record-keepers." Those who watch Mays’s visit to "The Foxhole" will learn her conclusion…And how valuable wouldst that be! For Andrea Mays knoweth instinctively what the author of "Midsummer Night’s Dream" understood: namely, that "It's not enough to speak, but to speak true."