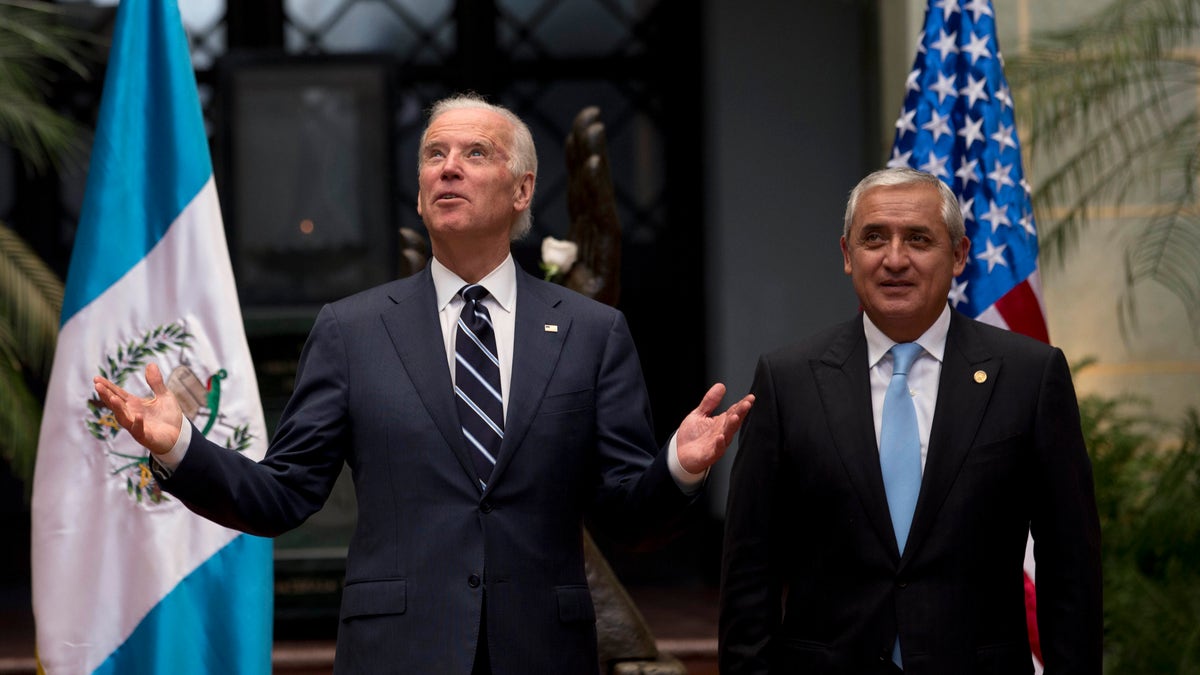

El vicepresidente de Estados Unidos, Joe Biden, a la izquierda, inicia una reunión de dos días con los presidentes del norte de Centroamérica para conversar sobre el financiamiento y prioridades de la Alianza Para la Prosperidad, el plan regional para frenar la migración. A la derecha está Otto Pérez Molina, presidente de Guatemala. (AP foto/Moisés Castillo)

Aside from his recent rapprochement with Cuba, President Obama has shown little to no interest in Latin America. It appears that our region has been delegated to Vice President Joe Biden, who started Monday another visit to Central America.

Biden’s trip is reportedly to offer a $1 billion aid package to countries of the “Northern Triangle”—Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. But will the aid actually do anything to help the severe situation of those countries?

In the five-year period between 2009 and 2014, the U.S. gave $400 million in aid to Guatemala, including $72 million for “human rights and democracy”— money that’s largely untraceable.

Last summer, Americans got a wake-up call when masses of unaccompanied, undocumented children flooded into the U.S. from the Northern Triangle. Immigration from those countries—most of it illegal—has grown quickly and quietly during the last two decades. At present, more than seven percent of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. are from the Northern Triangle. Those people, fleeing from poor and violent countries, have entered the U.S. in search of a greater economic future.

And now Joe Biden goes to the Northern Triangle with a time-honored solution: throw money at the problem.

How will this money be spent? Who will manage it? What oversight is in place to ensure the aid actually supports development rather than special interests?

In the five years between 2009 and 2014, the countries of the Northern Triangle received approximately $1.5 billion in aid from the U.S. Nearly half was directed at economic development, and Guatemala got the short end of the stick. With a population greater than the other two Northern Triangle countries combined, it received a paltry one-eighth of the economic development money.

Much of the aid ended up in programs and projects that did little to help the targeted populations. For instance, a 2013 audit of the USAID inspector general’s office in Guatemala revealed that water purifiers provided to poor people were useless because the recipients could not afford replacement filters. The same audit showed that USAID had funded scholarships for Guatemalan university students who were double-dipping with other financial aid received from private donors.

Perhaps the worst blunder in this aid package was not inefficiency or ineffectiveness or lack of oversight, but a flaw that ran deeper. A few months ago, members of the Dutch parliament inquired about reports that their government’s economic aid, as well as aid from the European Union, was being used to fund terrorist groups. Those reports raised questions about U.S. aid money as well.

In Guatemala, one of the recipients of U.S. aid is a group called CODECA, or “committee for the development of campesinos” (peasants). Judicial authorities have accused CODECA of being energy thieves—of stealing power from hydroelectric companies and selling it for their own benefit. Guatemala is well acquainted with such outlaw groups, which use their power—like Al Capone’s enforcers—to terrorize people who do not buy from them.

Can we be sure that U.S. aid does fall into the hands of such groups?

In Guatemala’s countryside, attacks on private property have become the rule—especially in areas where former guerrilla fighters hold sway, or where drug trafficking is present. These activities are creating enormous instability throughout the country.

In fact, the policies of the U.S. and other Western countries have been facilitating an enormous problem in the region. Radical or communist insurrections were defeated decades ago. It happens, however, that the defeated guerrilla fighters have been able to claim substantial power for themselves in the new governing structures. Today, it is precisely those radical factions which are being paid by U.S. and Western donors—whether the donors know it or not.

In Guatemala, this situation has developed in an especially clear way. The dramatic increase in migration is directly attributable to a new instability—to the very situation that Western countries are creating on the ground by their aid policies.

In the five-year period between 2009 and 2014, the U.S. gave $400 million in aid to Guatemala, including $72 million for “human rights and democracy”— money that’s largely untraceable. Ironically, during the same period, migration from Guatemala grew substantially, where 9 migrants out of 10 are men of working age who cannot find work in the formal labor force within Guatemala. When more than two-thirds of the labor force are in the “informal” sector, aid simply misses its mark.

As a result, many have voted with their feet. And left their homes, where no opportunity exists, to come to the U.S. from where they support their families through remittances. By a decisive margin, those dollars sent home from the United States are collectively the biggest asset in the Northern Triangle countries.

Will our aid continue to foster social instability? Or will it instead promote genuine economic competence? That’s the question contained in the huge bags of money which Mr. Biden is carrying to Central America.

Reny Bake is an economic analyst from Guatemala; and graduate of the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies. David Landau, an author and editor living in San Francisco, has worked on Guatemalan issues for 20 years.