Toby Harnden on heroism, sacrifice, and loss in Afghanistan

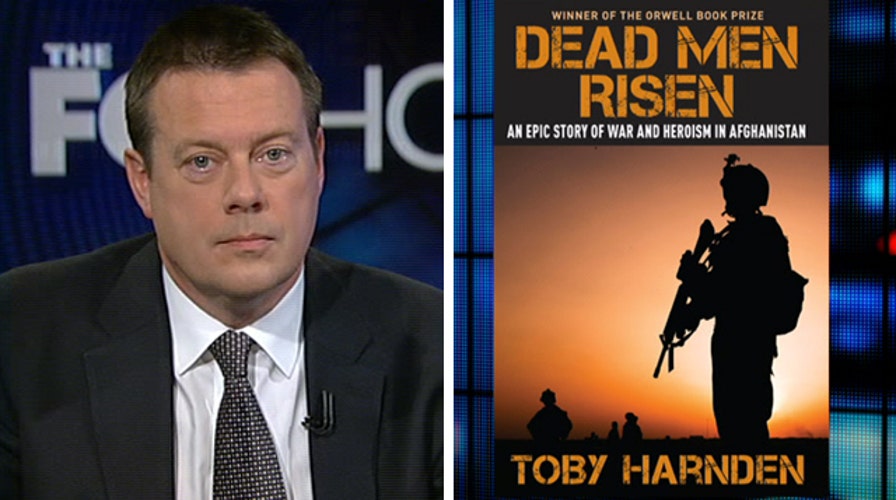

James Rosen speaks to author Toby Harnden about his book ‘Dead Men Risen: An Epic Story of War and Heroism in Afghanistan’

"I was stunned. I mean, I’d lost a friend," recalled Toby Harnden, Washington bureau chief for the Sunday Times of London. "Two little girls had lost their father ... So I just felt I had to get out there and find out what was happening."

The loss that rocked Harnden on July 1, 2009, when he was a Washington-based correspondent for "The Telegraph," was the death of his friend Rupert Thorneloe, a 39-year-old British Army officer killed by an improvised explosive device (IED) while commanding the Welsh Guards in bloody Helmand Province, in southern Afghanistan.

The two had first met in Northern Ireland, in the late 1990s, when Thorneloe was a captain in British Army intelligence. Himself a former naval officer, the reporter knew his friend to be a commander who, as Harnden writes in his new book "Dead Men Risen: An Epic Story of War and Heroism in Afghanistan" (Regnery History, 2014), "believed in leading from the front and by example ... drove his men very hard but himself much harder ... would never order a man to do something he would not do himself."

Indeed, Thorneloe was killed while driving a Viking armored vehicle at the head of a column of terrified Welsh Guardsmen – hardened soldiers who nonetheless became white-faced and vomited in fear at the thought of spending yet another day gently probing the rocky terrain before them for IEDs. As a former military aide to Britain’s defense secretary and a rising combat officer, Thorneloe was regarded as a sure bet by his peers, someday, to reach the rank of general.

Instead he became the first British battalion commander killed in action since the Falklands War in 1982; and his 1,500-man unit – 95 percent of whose rank-and-file were native Welshmen, and who had already lost their platoon commander and company commander – became the first British battalion since the Korean War to suffer such casualties, at these senior ranks, in the same conflict. In the end, Britain lost close to 500 service members in Operation Enduring Freedom.

Harnden reached Helmand within 45 days of his friend’s death. "When I got out there," the author said in a recent visit to "The Foxhole," "what I found was that this was a battalion that was under-resourced, didn’t have the right equipment, didn’t have the right counter-IED equipment, didn’t have enough helicopters, didn’t have the right vehicles ... Most British units at that point were in the same situation ... And Rupert’s death ... sort of encapsulated the things that he was arguing about ... He was making the case very, very forcefully to the brigade – and to the probable detriment of his career – that the helicopter system wasn’t working, that they needed better counter-IED equipment, and also that Operation Panthers Claw, which was the operation in which he was killed, was flawed in its concept ... It was one of these big, sweeping movements across territory where you sort of declare victory and announce, you know, several hundred Taliban dead but you didn’t have enough troops to hold the ground."

Over the next four years, in addition to sifting through thousands of secret documents, Harnden conducted hundreds of original interviews – including, for example, with Thorneloe’s widow, to learn what it was like when she received the dreaded knock at the door, and also with the British military man who actually knocked on Mrs. Thorneloe’s door.

"It sends a chill down my spine just sort of thinking about it now," Harnden told me.