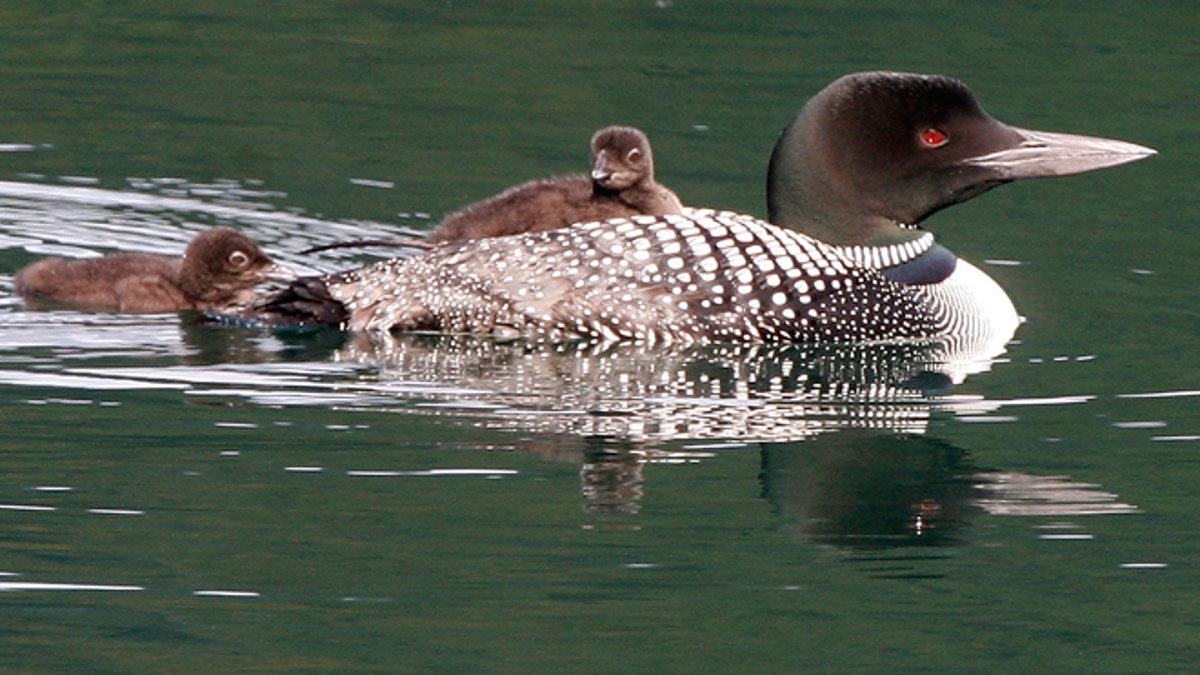

FILE - July 20, 2010: A young loon gets a ride on its mother's back as its sibling follows along in the waters of Mirror Lake in Calais, Vt. Once endangered, loons are among a number of species that had once all-but disappeared from Vermont which are making a comeback. Biologists and conservationists met on Oct. 23, 2014, in Burlington to mark the 40th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act. (AP Photo/Toby Talbot, File)

The fact that Congress has not enacted any statute establishing a federal land use policy for the nation has not stopped the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”) from aggressively using the decades-old Endangered Species Act to develop a process that imposes building restrictions on almost every inch of land in the United States. With the powers it has granted itself, FWS often determines where opportunities for jobs and growth can be created.

In the early years of the Endangered Species Act, FWS worked tirelessly to understand our impact on various species, their needed habitats, and effective preservation measures.

Unfortunately, Congress left the implementation of the Act on auto-pilot and has not reauthorized it since 1988.

Congress merely deemed the Act to be re-authorized as part of its appropriations process. This lack of congressional involvement allowed FWS to wander away from undertaking the hard scientific research of helping recover species to now crafting creative ways to use the Endangered Species Act to impose new mandates never envisioned or authorized by Congress.

[pullquote]

Environmental advocates now routinely use the Act’s citizen suit provision to sue FWS. The Service does not defend itself. Instead, it agrees to accept the environmentalists’ demands and binds itself through a court order, thereby remaining under court supervision until it completes the agreed upon terms.

Under this process, FWS and the environmental groups have developed an entirely new way for outside groups to commandeer agency policy and prioritize their demands while excluding public involvement in the settlement. This process has been termed “Sue and Settle.” Under these Sue and Settle agreements, outside groups drive the policy and regulatory agendas of the agencies, rather than the agencies themselves—or Congress.

Environmentalists’ power over FWS was cemented in 2011 when FWS entered into two mega Sue and Settle agreements with advocacy groups and agreed to consider another 757 new species for listing. These listings will give FWS such broad discretion over what is designated as critical habitat, that FWS could severely limit what activities and development can occur. In designating critical habitat for a species, FWS has exercised broad authority to restrict the types of activities allowed within the habitat.

Here are just a few examples that illustrate the potential impact of these Sue and Settle agreements:

• The range of the Northern Long-Eared Bat extends from Maine to Montana and down to Arkansas and over to Florida.

• Similarly, the Lesser Prairie Chicken has a range that covers much of the energy production areas of Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas and New Mexico.

• And, then there is the Sage-Grouse, whose habitat range spans 258,000 square miles across eleven Western states.

Listing just these three species would stymie the energy revolution now taking place in the United States as oil and gas exploration and production reach all-time highs. There are still hundreds more species to be considered in the next four years under the FWS’s Sue and Settle agreements. As more species are listed, there will be impacts on forest management, farming and cattle production, seaports, airports and highway infrastructure and the location of new factories.

By the time Congress caught on and attempted to restrain the aggressive actions of FWS, it was too late. Government was divided and Congress has been unable to pass a budget, Appropriations or laws to reverse such regulations or the Sue and Settle agreements. Oversight has been ineffective because congressional subpoenas have not been enforced by the Executive branch.

At this point, FWS controls what is built anywhere there is an endangered species and those areas, already vast, only continue to grow.

If this nation cannot build anything, anywhere, we will not be able to create jobs. We are at risk of creating a climate of endangered employment in many parts of the country.

It is time to create a policy making process that strikes the right balance between environmental protection and job creation. Part of that balance means better protecting habitats in this country where infrastructure can be built and opportunities created.