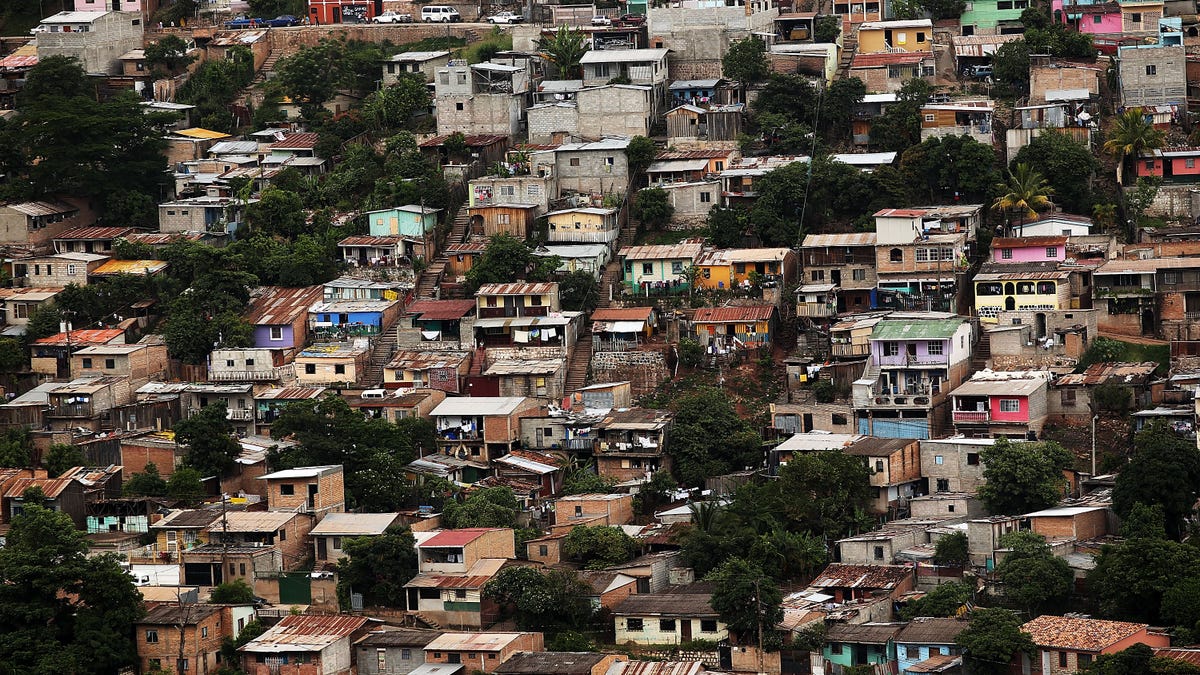

Slums are viewed in the capital city of Tegucigalpa, Honduras. (2012 Getty Images)

The Sao Paulo Forum, a group of Latin American leftist political parties and organizations, recently announced a gathering in Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital, on October 12. The stated reason for the gathering is to “contribute to the triumph of Honduran democratic forces and the consolidation of democracy,” in that Central American country’s upcoming presidential elections.

Why should a group of socialist and communist movements that includes Colombia’s armed guerrilla FARC make such an effort? And why in Honduras?

For Latin America’s left, the struggle inside Honduras is not a domestic political dispute; rather it involves shifting the balance of power in the Americas.

For one thing, on November 24th Honduras will elect a successor to President Porfirio Lobo, who came to office following the political crisis initiated by the removal, in June 2009, of then president Manuel “Mel” Zelaya.

President Zelaya precipitated a national crisis by pursuing a referendum asking Honduras if they wished to convene a constituent assembly in the next presidential term leading to changes in term limits, presidential succession and the form of government. The country’s Supreme Court ruled the measure unconstitutional. Zelaya ignored the court’s ruling and proceeded with the referendum, dismissing the head of the military command for disobeying his order to hold the poll. On June 28 the military arrested Zelaya and exiled him.

The Organization of American States, the Unite Nations, the European Union and the United States condemned Zelaya’s removal and expulsion as a coup d’état. Hugo Chávez threatened to invade the country in order to restore Zelaya. Eventually returning home, Zelaya formed a leftist opposition movement known as LIBRE (Liberty and Refoundation).

“Et tu, Mel?”

A conservative member of the oligarchy, Zelaya came to power in 2006 and shifted sharply to the left, pursuing an anti-U.S. foreign policy, persecuting opposition journalists, and pushing for a referendum to re-write the existing constitution. Most importantly, Zelaya aligned himself with Hugo Chávez’s ALBA, the Bolivarian Alliance of the Americas, an organization including Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua and a handful of Caribbean islands dependent on Venezuelan petroleum.

For many in the region, Zelaya followed ALBA’s game plan. Each ALBA-allied country, with the exception of communist Cuba and the Caribbean associate states, has established a “dictatorship of the majority” by means of constituent assemblies re-writing constitutions to remove legal barriers to centralized power and state control of the economy. The Bolivarian model uses a present majority to disable the checks of democracy and then consolidates a permanent presidential dictatorship. ALBA and the Sao Paulo Forum work hand-in-hand in pursuit of these aims.

Round Two

In Honduras’ upcoming elections Zelaya’s wife, Xiomara Castro, is LIBRE’s presidential candidate and currently leads polls with about 28 percent of voter support. An anti-corruption candidate follows her with 21 percent. Honduras’s traditional parties, the Nationalists and the Liberals, are the clear losers viewed as either corrupt or ineffective. Another 19 percent of Honduran voters remain undecided. Ms. Castro is riding this wave of anti-establishment sentiment and has made the call for a constituent assembly the centerpiece of her campaign.

Since the president is elected by a plurality of the votes, political polarization is a serious probability. With none of the major candidates expected to top 35 percent of the vote, approximately two-thirds of the electorate will not have voted for the winner.

This is where the Sao Paulo Forum, and their ALBA backers, comes in. Should Ms. Castro lose, they will raise the cry of electoral fraud seeking to delegitimize the entire process. If she does manage to win a plurality of the votes, the Latin American left will paint the results as a victory of the majority and increase pressure for a constituent assembly. This is one reason they have called for electoral observers from UNASUR, the union of South American republics, to substantiate results.

Clearly, the stakes are high for Honduras and the international left is redoubling efforts both to write the narrative, no matter what voters decide, and to pull Honduras back into the ALBA fold. For Latin America’s left, the struggle inside Honduras is not a domestic political dispute; rather it involves shifting the balance of power in the Americas. For the moment, the field of battle is in one of Latin America’s poorest countries.