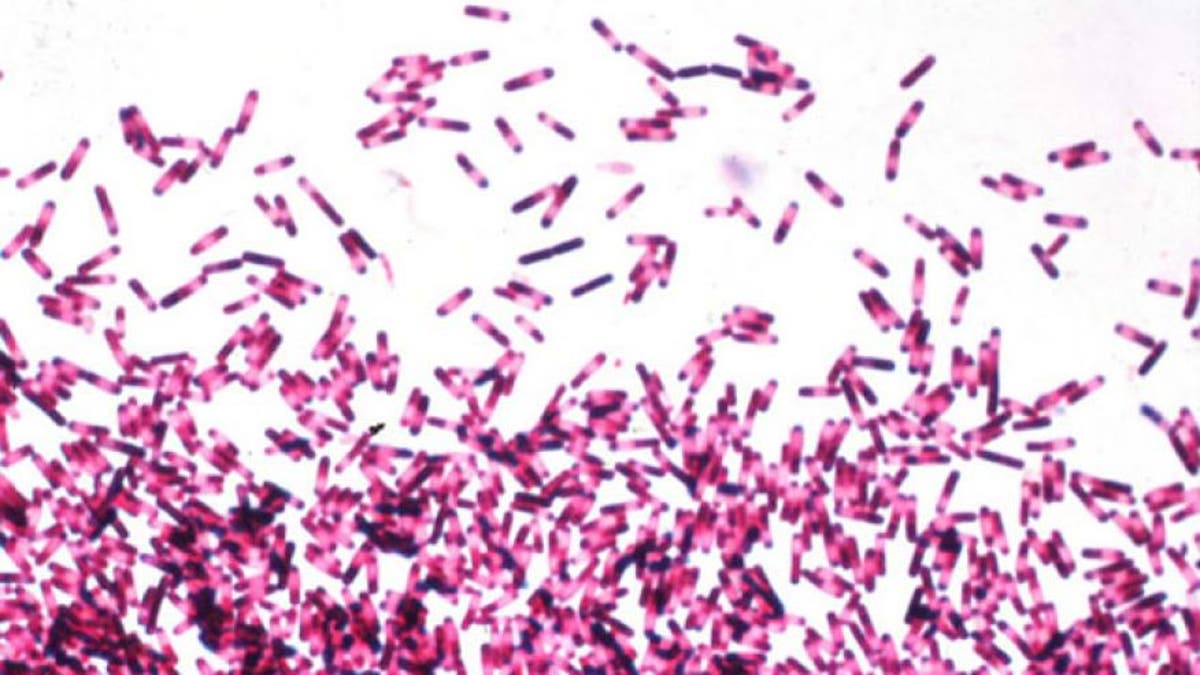

Clostridium difficile, or C. diff— a potentially deadly bacterial infection that’s gained attention due to its treatment by fecal transplants— occurs when the body’s natural balance of gut bacteria gets thrown off. Scientists believe that antibiotics commonly cause that disruption, especially in individuals who are young, elderly or immunosuppressed.

But researchers at Stanford University have identified another, possibly more preferable treatment for C. diff that does not wipe out beneficial gut microbes, as antibiotics are designed to do, and has been used in other clinical trials to treat unrelated conditions. In the study, published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the compound ebselen successfully disarmed a toxin that C. diff produces, preventing further intestinal damage incurred by antibiotics and previous bouts of C. diff, which has a high recurrence rate. Researchers chose to study ebselen due to its success in previous clinical trials, as well as due to its strong inhibitory properties.

“Unlike antibiotics — which are both the front-line treatment for C. difficile infection and, paradoxically, possibly its chief cause — the drug didn’t kill the bacteria,” senior study author Matthew Bogyo, PhD, a professor of pathology and of microbiology and immunology at Stanford, said in a news release.

Most C. diff infections occur in hospitals, clinics and assisted-living facilities, and antibiotics are successful at banishing it only 25 percent of the time. While effective, fecal transplants are a relatively new treatment, and each transplant contains a unique mix of intestinal microbes. Some of those microbes may have an adverse effect on a recipient’s body, the study authors write.

“We don’t have the tools to be able to screen for everything in a donor’s stool,” study co-author Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford said in the release. Sonnenburg added that gut bacteria play a role in obesity and neurological changes.

When researchers incubated C. diff’s primary toxin, Toxin B, in solutions with and without ebselen and injected it into mice, they found that after three days the mice with the ebselen-pretreated toxin lived. Those mice that received the dummy version, on the other hand, died within two days.

In another set of studies, researchers gave mice several rounds of antibiotics, then infected the animals with a virulent, multi-drug-resistant strain of C. diff to better emulate how C. diff typically takes hold on the gut. When administering an oral dosing of ebselen to the mice, researchers observed a reduction in clinical symptoms of the infection and saw no further damage was caused to the animals’ colon tissue.

Study authors said they plan to study ebselen in a clinical trial for C. diff next and expect to do so speedily, as the drug has proven safe and tolerable in previous clinical trials for chemotherapy-related hearing loss and for stroke.