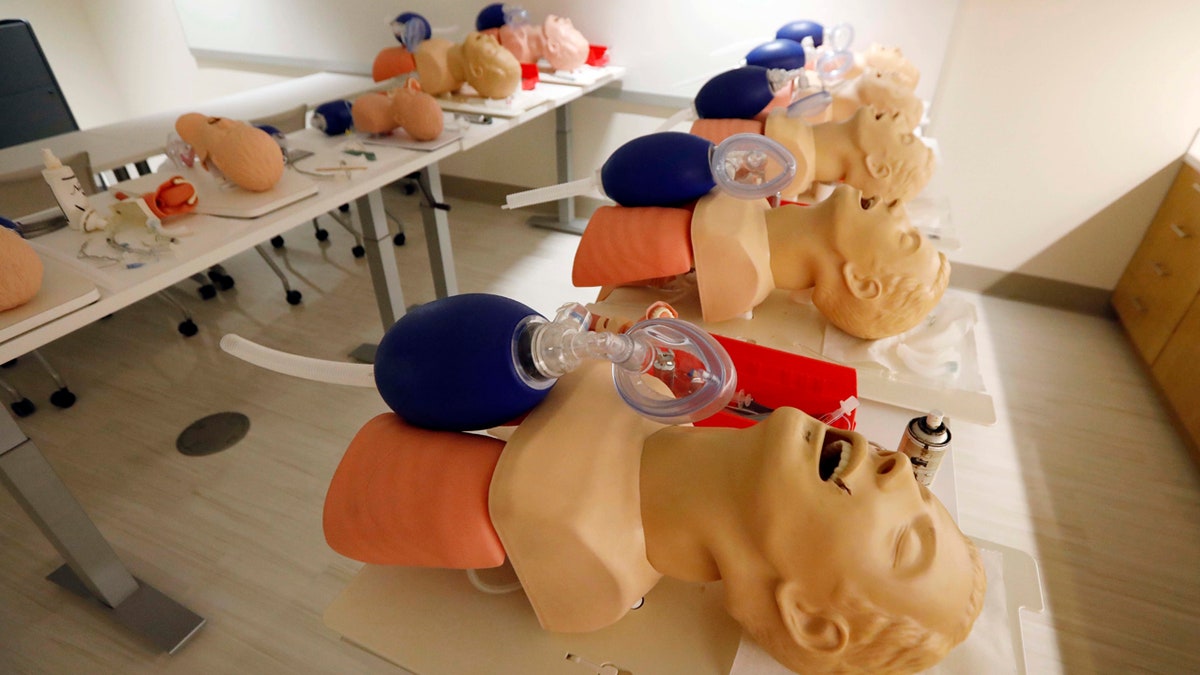

Male mannequins are arranged to train incoming medical students in CPR, in Jackson, Miss., Aug. 4, 2017. (Associated Press)

If you suffer cardiac arrest in public, just being a woman means you’re less likely to receive potentially life-saving CPR from a passerby, according to a new study.

One theory to explain the discrepancy: Strangers may be reluctant to undo a woman’s clothing and touch her breasts, even if it means they can save her life, says a lead researcher on the study.

“This is not a time to be squeamish,” said Dr. Benjamin Abella of the University of Pennsylvania, who urged strangers to get over their inhibitions and help in an emergency.

“Because it's a life-and-death situation,” he said.

"This is not a time to be squeamish. Because it's a life-and-death situation."

Only 39 percent of women suffering cardiac arrest in a public place received CPR versus 45 percent of men, and men were 23 percent more likely to survive, the study found.

The study involved nearly 20,000 cases around the U.S. and was the first to examine gender differences in receiving heart help from the public versus professional responders.

“It can be kind of daunting thinking about pushing hard and fast on the center of a woman's chest" and some people may fear they are hurting her, lead researcher Audrey Blewer, also of the University of Pennsylvania, said.

Abella said would-be Good Samaritans need not worry about touching the cardiac patient inappropriately.

“You put your hands on the sternum, which is the middle of the chest. In theory, you're touching in between the breasts,” he said.

The study was discussed Sunday at an American Heart Association conference in Anaheim, Calif.

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart suddenly stops pumping, usually because of a rhythm problem. More than 350,000 Americans each year suffer one in settings other than a hospital.

About 90 percent of them die, but CPR can double or triple survival odds.

Researchers had no information on rescuers or why they may have been less likely to help women. But no gender difference was seen in CPR rates for people who were stricken at home, where a rescuer is more likely to know the person needing help.

The findings suggest that CPR training may need to be improved. Even that may be subtly biased toward males — practice mannequins are usually male torsos, Blewer said.

"All of us are going to have to take a closer look at this" gender issue, said the Mayo Clinic's Dr. Roger White, who co-directs the paramedic program for the city of Rochester, Minn. He said he has long worried that large breasts may impede proper placement of defibrillator pads if women need a shock to restore normal heart rhythm.

The Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health funded the study.

The Associated Press contributed to this story.