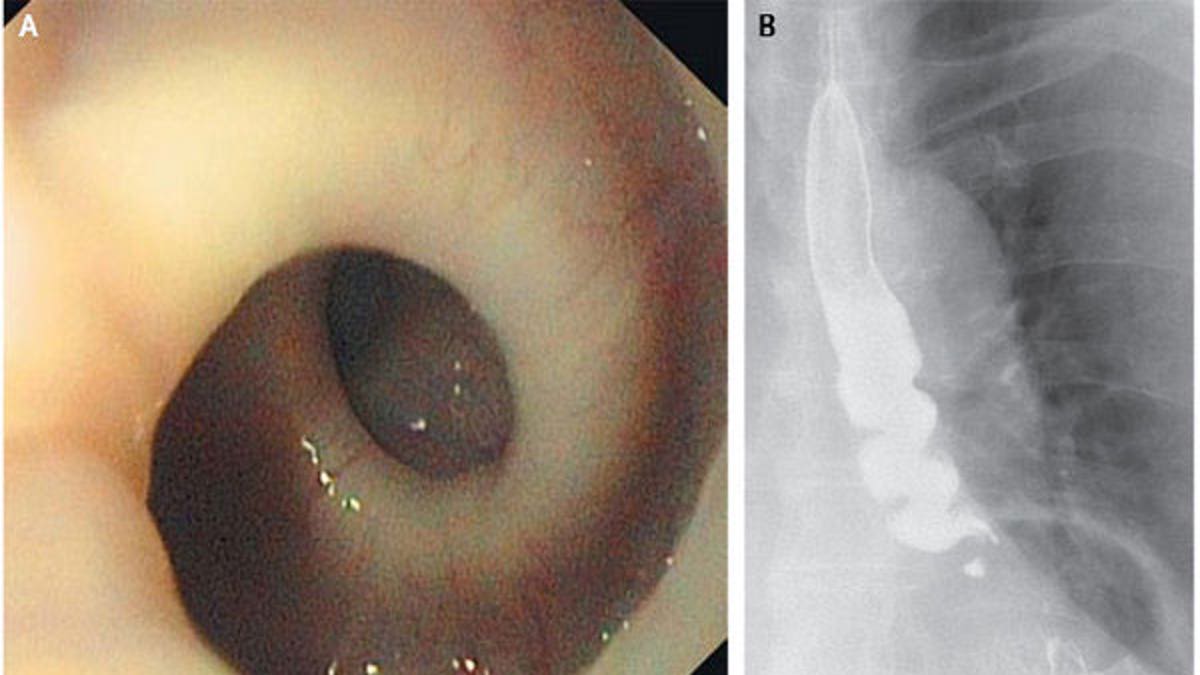

An 87-year-old woman had an esophagus that twisted itself into a corkscrew shape whenever she swallowed. Credit: New England Journal of Medicine ©2013.

An 87-year-old Swiss woman who suffered painful spasms in her chest turned out to have an esophagus that twisted itself into a corkscrew shape whenever she swallowed, according to a report of her case.

The woman had lost 11 pounds in the past several months, and told doctors she had cramplike spasms shortly after eating.

[sidebar]

Her doctors performed an endoscopy and found that, when she swallowed, her esophagus had the same helical shape as a playground twisty slide.

X-ray images revealed the startling, corkscrew shape taking form.

"The magnitude of this finding was extraordinary," said Dr. Luc Biedermann, of the University Hospital Zurich, who treated the woman and reported the case in this week's New England Journal of Medicine.

Although the condition is unusual, it has been encountered before. In fact, another elderly female patient, 89 years old, who complained of difficulty swallowing, abdominal pain and frequent belching, also turned out to have her esophagus twisting into a helical shape when she swallowed, according to a 2003 case report in the same journal.

Dr. Michael Vaezi, who specializes in treating "esophageal motility disorders" at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Tennessee, said he has seen the condition many times.

While primary care doctors may rarely see this disorder, at his center, they "encounter these patients on weekly basis."

Dr. John Pandolfino, a gastroenterologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, explained that this strange phenomenon occurs because of the way the muscles of the esophagus contract. Normally when a person swallows, the muscle fibers that encircle the top of the esophagus contract first, and then as they relax, the muscles just below them contract, and this wave of contraction continues all the way down to the stomach.

But in a person with this condition, all the muscles contract simultaneously. As a result, rather than moving food downward toward the stomach, the muscles pull the esophagus itself into a spiral shape.

Why this happens, however, is still unknown. Vaezi said "some have speculated that gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) could be playing a role."

While there is no cure for the condition, the doctors in the study tried to treat the patient's symptoms by giving her high-dose proton-pump inhibitor drugs, which are typically used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease, and long-acting calcium channel-blockers, which Vaezi said can help to scale down the "squeeze" of the esophagus's contractions.

In this patient's case, neither drug had much of an effect.

In some cases, "Botox of the esophagus has also been tried with limited success," Pandolfino said, "but it only lasts six to 12 months, so it's not a good long-term solution." A last-resort solution may include surgery of the esophageal muscles.

Copyright 2013 MyHealthNewsDaily, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.