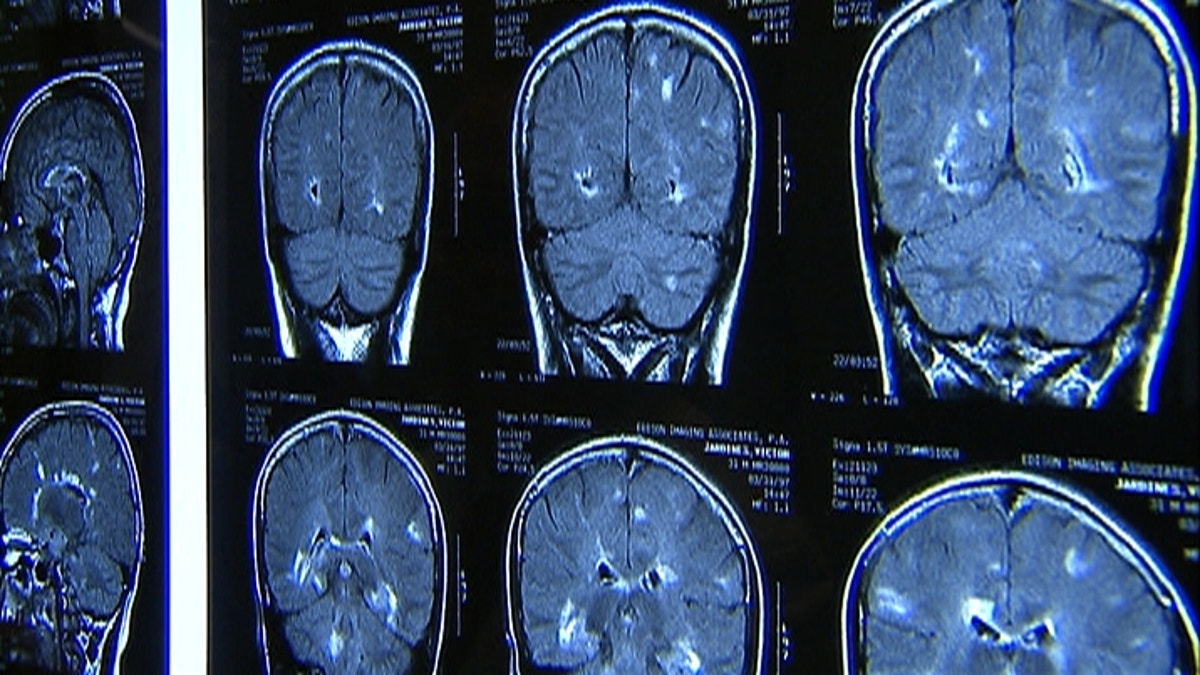

(Courtesy FNC)

A new study has found an association between childhood obesity and the risk of multiple sclerosis (MS) in children and teenagers. Though still rare, pediatric MS is more common now than it was 30 years ago.

Experts have theorized that obesity, because it causes a low-level state of inflammation, may contribute to MS. Two previous studies in adults have examined this link, both suggesting that moderate obesity at age 20 but not at other times in life doubles the risk of MS. Yet, these studies are small and have other flaws.

In this study, published in the online issue of the journal Neurology, researchers identified 75 children and adolescents diagnosed with pediatric MS between the ages of 2 and 18. Body mass index (BMI) from before symptoms appeared was obtained. The children with MS were compared to 913,097 children without MS. The researchers grouped the children by weight—normal weight, overweight, moderate obesity and extreme obesity.

The study found that 50.7 percent of the children with MS were overweight or obese, compared to 36.6 percent of the children who did not have MS. The association between weight and MS was only seen in girls, and was greater in Hispanic girls in particular. It was not seen in boys.

The study found the risk of developing MS was 1.5 times higher for overweight girls than girls who were not overweight, 1.8 times higher in moderately obese girls compared to normal weight girls and nearly four times higher in extremely obese girls.

"In our study, the risk of pediatric MS was highest among moderately and extremely obese teenage girls, suggesting that the rate of pediatric MS cases is likely to increase as the childhood obesity epidemic continues," the authors wrote.

“Menstrual cycle levels of female sex steroids have been shown to increase the risk of MS in animal models by promoting inflammatory mediators of autoimmunity,” explained study author Dr. Annette Langer-Gould, of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Department of Research & Evaluation in Pasadena.

Fat tissue also produces these pro-inflammatory mediators.

“We speculate that these extremely obese peri-pubescent girls are getting a double dose of pro-inflammatory mediators and thereby increasing their risk of MS and MS-like illnesses,” she said.

The study found no association in boys, but the authors suspect that the effects of obesity may show up later in men, as they reach young adulthood.

“It is plausible that extremely obese boys--who have higher estrogen levels than normal weight boys, but whose estrogen levels are not as high as girls—will have an increased risk of MS over their lifetime particularly if they remain obese,” Langer-Gould said.

Even though pediatric MS remains rare—1.7 in 100,000 kids—parents of obese teenagers should pay attention to symptoms such as tingling and numbness, limb weakness and loss of bladder control. If these symptoms arise, the child should be examined by a neurologist, Langer-Gould said.