(Reuters)

In two new studies published this week, scientists have gained new insight into how exposure to antibiotics affects the body and may increase the risk of obesity, notably in children.

In one study, published in the journal Nature, researchers from the New York University School of Medicine administered low doses of antibiotics to mice over a period of six weeks. They found the mice that were given antibiotics gained about 10 to 15 percent more fat mass than the control mice that did not receive antibiotics over the same time period.

The researchers believe this excess fat gain may in part be explained by the antibiotics’ effects on the gut microbiome – or community of bacteria in the stomach – as well as the other organs.

They observed that while the antibiotics had no effect on the number of bacteria in the stomach, the medications significantly altered the composition, or levels, of different types of bacteria present.

“It’s like taking a census of a city,” study author Dr. Ilseung Cho, assistant professor of medicine and associate program director for the Division of Gastroenterology at the NYU School of Medicine, explained to FoxNews.com. “The population of the city didn’t change, but the numbers of different types of individuals were altered.”

The composition change was observed at multiple levels, among both larger and smaller subtypes of bacteria.

In addition, the researchers found increases in the concentration of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the gut microbiome, as well as increases in bone density and an amino acid called glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP).

SCFAs are used as energy sources in the body and, in part, act on the liver to aid in the production of lipids – meaning an uptake in SCFAs also leads to an uptake in lipid production, Cho explained. Meanwhile, GIP produces hormones related to metabolism and obesity and could also help account for the gain in fat mass.

The increase in bone mineral density – which was temporary – was not related to the obesity findings, Cho said, but rather “suggests changes to the gut microbiome affect multiple organ systems within the body.”

“Just from this paper,” he added, “we know the changes to the gut microbiome can affect bone, liver and overall [obesity]…It’s possible and probable that the gut microbiome plays a role in other health issues besides obesity, such as heart disease, colon cancer, etc.”

Human evidence

A second study, conducted by a separate group of NYU researchers, added to these results, finding that infants exposed to antibiotics appear to have a greater risk of becoming obese later in life.

“I found the studies to be very complementary,” study author Dr. Leonardo Trasande, associate professor of pediatrics and environmental medicine at NYU School of Medicine, told FoxNews.com. “The studies examined the response to antibiotics in two species, which in the scientific community is very supportive of the possibility that antibiotics do contribute to obesity – though neither study is definitive.”

Trasande’s study, published in the International Journal of Obesity, looked at antibiotic use in 11,500 infants in the United Kingdom between 1991 and 1992 and followed up with the participants up until age seven.

The results indicated that infants given antibiotics before 6 months of age tended to have accelerated weight gain, out of proportion to height, and a 22 percent increased risk of being overweight at age three. However, the effect was not seen in infants exposed to antibiotics older than 6 months of age.

“This indicates the earliest windows of exposure are when the infants are the most vulnerable,” Trasande said.

A new approach to fighting obesity

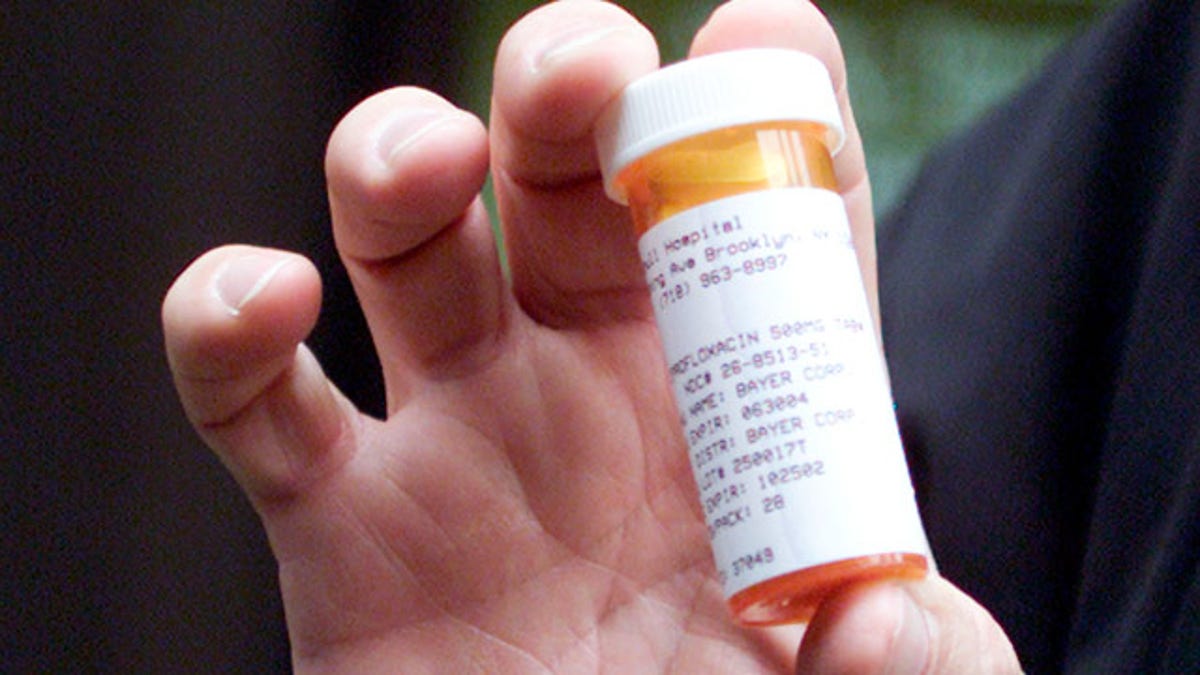

According to Cho, the study findings don’t mean you should toss your – or your child’s – antibiotics if they’re prescribed by a doctor.

“I’m worried people will take the results the wrong way – like, ‘I shouldn’t take antibiotics because they will make me obese,’” Cho said. “You should keep taking your antibiotics as prescribed.”

Instead, he said the new data is simply the first step in understanding the importance of the gut microbiome in regards to obesity, as well as in regards to overall health and disease.

“It would be really great if one day we could figure out how the gut microbiome could lead to obesity in humans, but this is a field that is still in its infancy,” Cho said. “We’re learning to appreciate how complex these interactions are and as we get more information, we may find that we could alter the microbiome in some way and improve somebody’s health.”

Trasande added: "We typically consider obesity an epidemic grounded in unhealthy diet and exercise, yet increasingly, studies suggest it's more complicated. Microbes in our intestines may play critical roles in how we absorb calories, and exposure to antibiotics, especially early in life, may kill off healthy bacteria that influence how we absorb nutrients into our bodies, and would otherwise keep us lean."