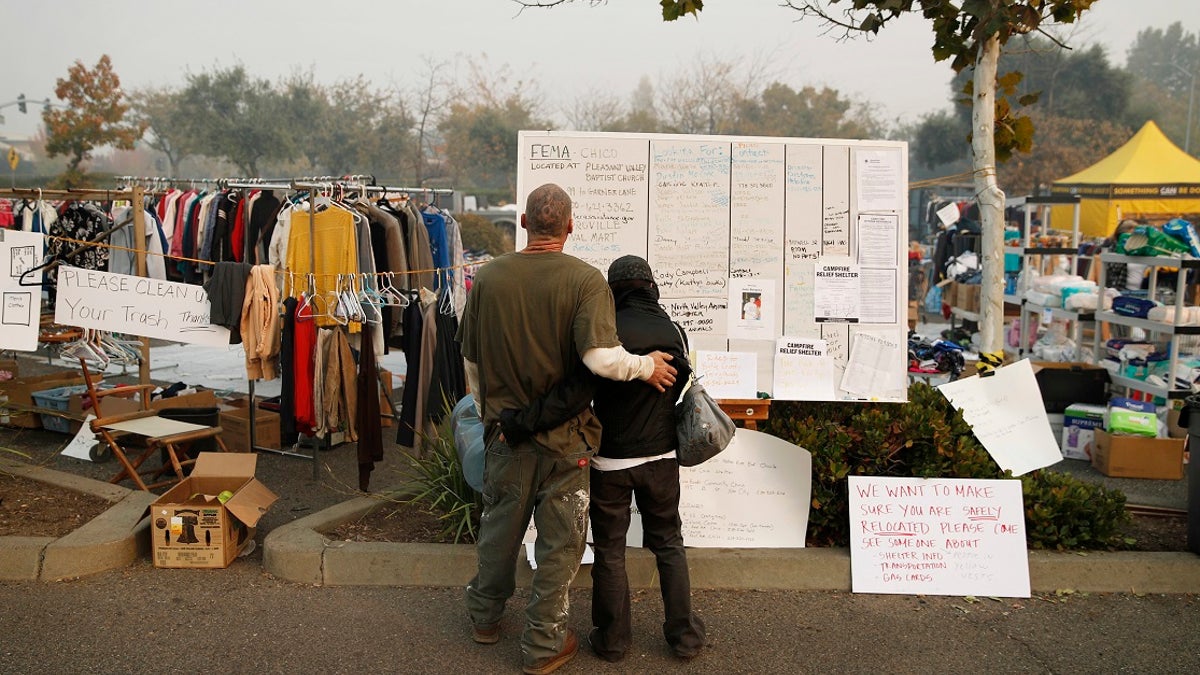

Tera Hickerson, right, and Columbus Holt embrace as they look at a board with information for services at a makeshift encampment outside a Walmart store for people displaced by the Camp Fire. (Associated Press)

As firefighters in California begin to get a handle on the deadly wildfires that have ravaged both ends of the state and destroyed thousands of homes this past week, those affected will soon face the potentially daunting task of having to find permanent housing in a state already experiencing a massive housing shortage.

The Camp Fire in Northern California decimated the town of Paradise, killing at least 71, and destroying 90 percent of its housing stock, turning homeowners there into refugees.

Some have been staying in motels, shelters or with family and friends before they attempt to find permanent housing or rebuilding their homes.

But California ranks 49th in the U.S. in housing units per capita. Factors include the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978, which limited the amount of money cities and counties could spend on new housing, and the job booms in technology and other fields that have attracted residents from out of state faster than new housing can be made available.

As a result, “There is no way that the current housing stock can accommodate the people displaced by the fire,” said Casey Hatcher, a spokeswoman for Butte County, where Paradise and surrounding towns ravaged by the Camp Fire are located. “We recognize that it’s going to be some time before people rebuild, and there is an extremely large housing need.”

“There is no way that the current housing stock can accommodate the people displaced by the fire. We recognize that it’s going to be some time before people rebuild, and there is an extremely large housing need.”

Some of those displaced have resorted to extreme measures while contemplating their next move, the Los Angeles Times reported.

"I just want to go home," said Suzanne Kaksonen, a Paradise resident now staying in a tent city in a Walmart parking lot in Chico with her two cockatoos after her 800-square-foot home was destroyed. "I don't even care if there's no home. I just want to go back to my dirt, you know, and put a trailer up and clean it up and get going. Sooner the better. I don't want to wait six months. That petrifies me."

Suzanne Kaksonen, an evacuee of the Camp Fire, and her cockatoo Buddy camp at a makeshift shelter outside a Walmart store in Chico, Calif. (Associated Press)

DeAnn Miller, 57, who also stayed in the tent city, was homeless for over a year before her uncle gave her a travel trailer. She evacuated so quickly that she didn’t event take a change of clothes.

“To just get a home again and to lose it like this …” she said before trailing off. “I don’t want to be homeless again.”

“To just get a home again and to lose it like this … I don’t want to be homeless again.”

Further south near Los Angeles, the Woolsey Fire destroyed 35 homes. Evacuees need shelter for now, but eventually, they will need homes.

Patty Saunders, 89, barely escaped her mobile home community where she lived on a $900 monthly Social Security check. She had hoped to stay with her daughter outside Los Angeles, but she too was forced to evacuate her home.

People sit by their tents at a makeshift encampment outside a Walmart store for people displaced by the Camp Fire. (Associated Press)

“What is happening with California, dear?” Saunders said, covered in blankets in a church gym. “It’s going to be tough.”

Some Southern Californa evacuees who fled their homes have been allowed to return.

More than 81,000 people across the state have evacuated from their homes in the week since the fires began. Housing experts said while the state’s economy from its ports to Hollywood and Silicon Valley has boomed, housing supply has failed to keep up with demand, according to the New York Times.

As more people transplant themselves, the demand only grows.

From 2009 to 2014, California added 544,000 new households, but built only 467,000 units over the same period, according to the McKinsey Global Institute.

“We’ve had a huge increase in population and a huge increase in jobs, and we do not have anywhere close to the supply of housing to put people,” said Carol Galante, faculty director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at University of California at Berkeley. “There is no margin when there is a disaster; there is no cushion at all.”

Butte County was already plagued by a severe housing shortage before the Camp Fire, Ed Mayer, executive director of the county’s housing agency told the Sacramento Bee, adding the vacancy rate was at 2 percent.

Many Paradise residents will face difficulties rebuilding their homes because of their limited financial means, he said.

“Big picture, we have 6,000, possibly 7,000 households who have been displaced and who realistically don’t stand a chance of finding housing again in Butte County,” Mayer said. “I don’t even know if these households can be absorbed in California.”

President Trump will meet with Gov. Jerry Brown and Governor-elect Gavin Newsom during a visit to the state Saturday to tour the damage and meet with those affected. Trump previously threatened to withhold federal funds to the state while blaming California for "gross mismanagement" of its forests.

But the president later toned down his rhetoric, in a Twitter message Wednesday.

"Just spoke to Governor Jerry Brown to let him know that we are with him, and the people of California, all the way!" Trump wrote in one of several messages.

One possible housing solution for California would be for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to provide trailers for people to live in while their homes are being rebuilt.

For now, authorities are focused on providing relief.

“This is a tremendous strain in an already difficult situation,” said Shawn Boyd, a spokesman for the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.